Shades of Bruise: A Review of Dawn Lundy Martin’s Life in a Box is a Pretty Life

14.04.16

Life in a Box is a Pretty Life

Life in a Box is a Pretty Life

by Dawn Lundy Martin

Nightboat Books

104 p. / $15.95

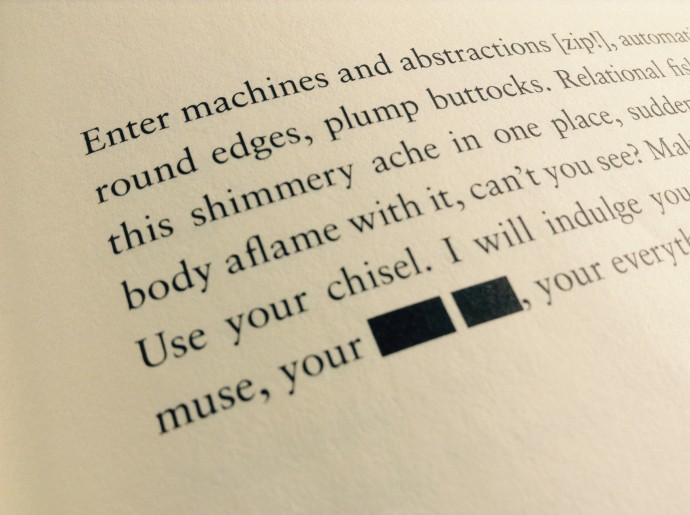

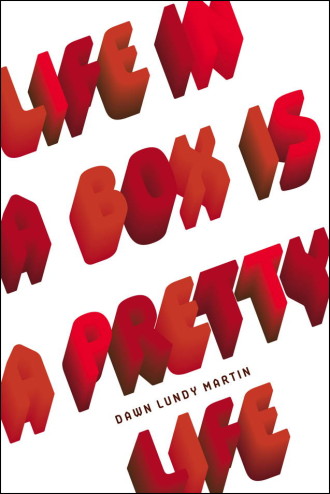

When one considers the average box, one probably thinks of a modular square-like something. Units capable of being stacked and/or arranged. One thing on top of another thing. Possibly many things stacked on top of a singular thing. A disastrous pile-up of situations and events. When one considers a box, one might think of a row of boxes. Or a towering column of boxes. The raging and reddening font that reads “LIFE IN A BOX IS A PRETTY LIFE” is the claim made by the book’s cover/title, but these poems—these shadow boxes—are not particularly pretty. Or capacious. There’s really no room left for storage. They are, in fact, filled and pulsing with nightmarish bricolage. Overflowing, like a computer screen of endlessly scrolling code, an American history of brutal horrors, the interior walls of Dawn Lundy Martin’s Life in a Box is a Pretty Life have been painted in shades of bruise.

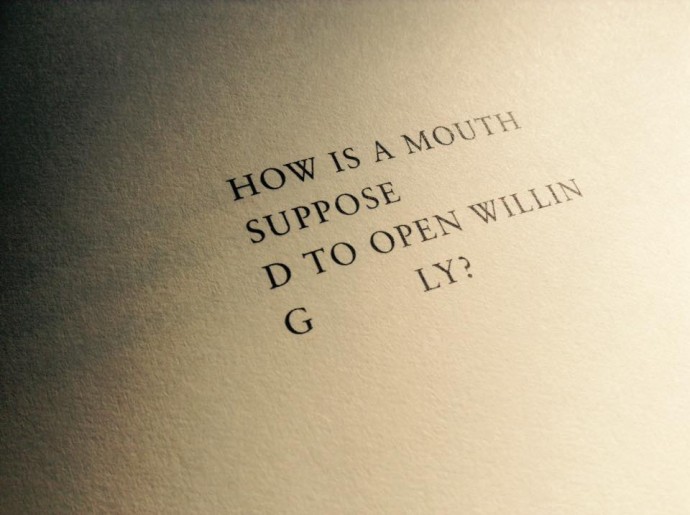

For anyone suspicious of prose poems, block-shaped poems, for any squares out there—rest assured, the voices lurking within these boxes—through cracks in walls, through fly-infested throats, through the white eyes of ghosts—they will spring at you, booby-trap-like, with a cunning array of uncompromising lyrical ambushes. Martin writes,

Life inside grid object, replace faces with armored ducks, drive off fucking cliff, get all damaged after raging. What holds the structure: giant ministries, giant everything! They don’t want you to hang yourself. Instead you survive. Spring is here! Let’s poison the grass to make it shine. We are shiny people. If you were to hang yourself, you wouldn’t die, you don’t know how to die. Hurt calm at edge of bay. Today, calm not choppy. Who’s digging inside the earth for wooden faces? Super structures of defense lined up outside your window. I’m happy!, you sing. Register at the desk, indicate whether you understand sentences.

As the reader wanders through box-like assemblage after assemblage, they will quickly feel more and more confined. Grid-imprisoned and under constant surveillance, the reader will begin to understand that many things in this ‘pretty life’ have been intentionally rendered as sick or poisoned. The grass is poisoned, but it still shines. Violent defense units are everywhere, but one is still expected to sing. The spring season is present, but the only ducks are the armored kind. Armored units. Targets. Like the cave-like, box-like device we know as computer, with its host of mimetic properties and its interior constantly at odds with viral worms and Trojan horses, Martin’s boxes/poems read like a surreal and tragic series of system failures. Corrupt, disrupted, viral, and trending, the American system of policing (“giant ministries, giant everything!) expects bodies to be compliant and obedient. But, no matter how compliant, too many bodies, more and more bodies, every day bodies that are not white bodies, are experiencing despicable acts of police brutality. Day after day, these bodies are being subjected to wrongful violence. The horrifying police state of Martin’s poems, the carceral, panoptic eye within these boxes, demonstrates how a life in a box is very much a controlled life. To rupture status, to rupture the dishonest food chain-like system, Martin’s poems frequently associate light (“We had steel barriers to protect us from the sun”), brightness (“figures in white” always playing the victim), and whiteness (“When turned white from irons”) with mental and physical violence. In fact, in one poem, the very word, “white” becomes a struggle to utter:

“To be a nice whi— whu—”

I think of the contorted poems of Life in a Box is a Pretty Life as themselves boxes. Imprisoned voices. Entering one of these boxes might feel more like something akin to giving one’s self over to crisis. Or chaos. How exactly should one feel about their participation in these boxes? I think it depends on the reader. The reader could possibly feel like they’re looking into a mirror; another might feel like they’re gazing down a corridor of Hell. Again, the reflection/refraction depends on the reader. Perhaps a reader will feel like they’re stepping into familiar territory, or they might feel explicitly uninvited once immersed within these boxes. Or even suddenly, violently deformed by these boxes. Defamiliarized and/or re-shaped by these boxes. Strengthened and/or bolstered by these boxes. One might also not know how to feel. These boxes might induce sweat, nausea, discomfort…

“When the head is shoved it naturally resists. Covers her dark face in / a black cloth (could be a hood).”

Martin’s grotesque and challenging boxes are affect-heavy and expansive in eye-opening, often uncomfortable ways. But it’s not as though the author wasn’t specifically anticipating a reader’s—or critic’s—discomfort: “Reviewers want these poems to be more hopeful,” a boxed-in sounding voice says in one poem.

The police are so young. They do not hear the wailing. Wailing, I’m told, is a figment of your imagination. What to know of the body’s refusal to open, of its hidden cave? Put the cave inside another cave so no one can reach it.

One of the most fascinating things about the book is how there is an implied fakeness to some bodies and a more explicit marquee-ness to other bodies. The boxed-in voice of these poems reads as though it has been cruelly, intentionally misled (“Wailing, I’m told…”), infected with untruthful data. Sometimes the speaker of these poems is asking, “Who’s digging inside the earth for wooden faces?” In the book’s title poem, flowers feel closer to artificial frangipani fakeness. Fakeness so often feels synonymous with Death in these poems. Martin writes, “Breathe into my bag. Flower.” Like carbon dioxide, the concept of flower feels already used up. Life as already exhausted. In another poem, a body, linked with “I,” is acknowledged by the speaker as already “gesture” already “antagonism” already a “wig.” This idea of one’s self hood being associated with a “wig” or the “wig” being something available to another (as an opportunity to engage in a cruel mimicry) echoes the violence of the police who choose “not” to hear the wailing of innocents. This brings me to marquee-ness:

Which of our distinctions bears unreasonable resemblance to other noticeable features? Alternatively, phenotypes. Body draped as marquee. Despite the fact that they want us to desire “a regular mode of living,” we satiate the silver cylinder and tighten.

It was difficult to read “draped as marquee” and not dwell on Kenneth Goldsmith’s 2015 hijacking of Michael Brown’s body by way of autopsy report or Ti-Rock Moore’s sculpture of Michael Brown’s body being displayed in a Chicago art gallery. This foul repeat of “Mine!” is becoming an exhausting and sinister practice via white artists. The spectacle of the death of the physical body of the other, its marquee-ness, for some reason, entices white American artists and becomes something they need to possess and/or inhabit. Something they need to alter and/or change. Something they must have. Something they want to charge admission for, something they want to unveil before an audience. Or, as far as Goldsmith is concerned, something they must “massage” into submission. It becomes a matter of ownership. Goldsmith says it worst in an issue of Rhizome when he is talking about “retained foreign objects” and his list of iTunes song items: “My computer has thousands of such displaced items on it. I can’t translate them. The song that shows up in iTunes. I can’t tell you where it came from. I wish I knew. The song has no identifying information, no ID3 tags, no provenance. But I like it. I tame it by tagging it, domesticate it by filing it on my hard drive. It becomes mine.” His treatment of Michael Brown’s body was no different.

The mutative properties of the driftwood-like “I” that floats, collects, scatters in poem after poem of Life in a Box is a Pretty Life was another presence in these poems that I found particularly compelling. Martin writes, “I am driftwood. Now, the crux: I opens promise heaps. (Impossible opening.).” In thinking of the heaps of body of the poems’ speaker as “driftwood,” as a possible nuisance, as something gone astray, as debris or remains of something larger, as chaos!—I found myself associating the “piecemeal” accumulation of “I” with various passages addressing gender roles like: “A boy is not a body. A boy is a walk” and “[…] but first I write the phrase ‘the boy’ to refer to me, and then I write ‘the body is trauma,’ never achieving my original intention.” In swimming these floating pile-ups of driftwood, in entering and exiting the many boxes, there were moments when the “I” felt like it underwent increased complications in an effort to wrestle with gender norms. Something would latch on to the driftwood, something else would break off, etc. Especially when Martin writes, “I insertion into vagina. When the rains come, we hear unmemory cloaking its needs.” From the very beginning of the book, it feels like there is something the reader is not permitted to know, a constant feeling of censorship, a constant practice of omission. Martin further explores the complications brought on by gender when the technology of clothing is addressed (“Without clothes the body feels its own flesh suddenly”) and I read that type of jarring loosening or “unwinding” as a challenging navigation of the human body as a perpetual storm.

Life in a Box is a Pretty Life might be one of the most important books to debut in 2015. I can easily see this work in conversation with the boxes of Joseph Cornell; the shelves of Rashid Johnson; the suffocating dreams of Hervé Guibert; or the disturbingly engrossing works of Kara Walker. Poetry—art, in general—might not always feel “hopeful,” but that doesn’t necessarily render such hopeless feelings useless. Sociality must be constantly challenged. Unapologetic, uncompromising poetry is capable of challenging the unjust prosecutors that continue to victimize an innocent American public. These poems, these cavernous reliquaries, these linguistic panopolies of Dawn Lundy Martin could possibly energize or enrage, but either might be better than deceiving one’s self. Telling one’s self that everything is fine. That all figures of authority are good and fair in America. That there is no problematic prison regime. That there is no need for reform. That life in a box is a pretty life…