What Could This Possibly Be the End Of?: On Kate Greenstreet’s The End of Something

03.04.18

The End of Something

The End of Something

by Kate Greenstreet

Ahsahta

$20 / 176 pp.

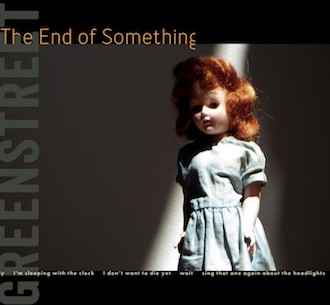

Kate Greenstreet’s latest book, The End of Something, opens with a quote on the first page, paired with a picture of a wide-eyed redheaded doll: “I dreamed I was a thousand years old and then, when I woke up, I was a thousand years old and I thought: am I dreaming?” The book itself is a dreamscape, and as I’ll show, there are different facets of what Greenstreet is doing that have played out in her previous books, too.

The book has all of Greenstreet’s well-known varied voicings and form in it: it’s the perfect follow-up to any of her other books, all of which echo one another in repeating patterns and lines. The speaker seems to lament something, or at least it feels as if she is lamenting missed encounters and human relationships that never quite transpired. In previous books, she has written about the impermanence of life and love, and she continues that trend here, and she does it beautifully.

In the first section of The End of Something, which follows the lovely quote I just mentioned, she writes:

A psychic once told me I had the mind of a nun. As if there would be only one kind, for nuns. The offices of seers we consulted in the South sometimes had chickens. The vestibules were swimming with the poor—bobbing, drowning, in our lake of dream and wishes.

Tell me everything you want to do while there’s still time.

Keep in touch.

I get the sense that the speaker is a bit removed from the addressee here: “Keep in touch” is all she ends with. She seems to want to say something to the addressee, to have a conversation, but the last line lets us in on the transience that the narrator feels as she moves through the world. The book is peppered with lines like this, that truly knock us over with their brevity and ability to, as Frank O’Hara would say, “cut with a word.”

In 3. “Leaves Fell,” Greenstreet again gives us a brief character sketch, with the same Objectivist-tinged lineation and brevity, hence:

He wasn’t born blind.

He had witnessed an

accident.

They were boys,

they were vulnerable.

That didn’t make them good.

Greenstreet has an uncanny ability to get to the heart of a characterization with a few words, and she shows it beautifully in this book. The lines that are so brief here soon convert to paragraphs, and she weaves a story replete with traveling and familiar names. In 7. “This Is a Traveling Song,” we get the following:

The escaped convict’s story is a traveling story.

The language is full of gaps and problems of tense.

One time you asked for a sign and found a shell.

Add one minute for every thousand miles.

Greenstreet’s knack for getting the words right is evident throughout The End of Something. She uses a style probably influenced by the Objectivist poets like George Oppen and Lorine Niedecker in their voicings, and her work is both precise and haunting. We weave through a digression about cows (wow!), and then come to the following page, with just this, simply:

13. One Black Leaf

What was your mother’s name?

In the following poem, 14. “This Must Be the Place,” Greenstreet writes of a familiar scene: but what is the setting of this scene? It seems to be a place that is haunted by memories, as much of her work is, and it is a house, after all, so it’s familiar to all. It’s a “house I used to live in,” where “grass was growing in the rooms.” She writes about a summer place that doesn’t seem to have a real home, for it’s only transient. Apparently, someone is “throwing money from the bridge,” and the secret to this living is being “‘in,’ more secret than before.” But this story doesn’t have quite the happy ending we would expect: “In the evening she went down. / Everything I knew of evermore.”

Apparently, in this dream, we are dealing not just with a “refuge of sinners, cause of our joy,” but we are also dealing with wisdom, who had “built herself a house in the dream.” The speaker is “twins, … looking for something.” I wonder, as I read this, what is this meant to be a mirror of? Some would say that mirrors are misplaced, but as Greenstreet writes it, something changes in the dream to become more beautiful, and it’s difficult to figure out exactly what it is that is changing so rapidly. The speaker clearly seems to be living in a Lacanian dream, a dream that is taking place in a mirror, perhaps where doppelgangers abound.

Greenstreet writes about “‘the lonely detective,’ “ a figure who appears here in 22. “Special Blindfold.” I wonder if this same haunted figure isn’t the ghost that appears in a later poem, 29. “I Would Like to Get Rid of This Because It’s Dead”:

How she got to be a ghost was that she ate a plate of spiders—a plate of plastic spiders that were meant to scare people, not to be eaten. The little sisters told me this.

She writes about math, about M-A-T-H, about mail arriving, and I wonder where exactly we are in this dreamscape…. She writes about the planet Mars, and you wonder why. “If you lived on Mars, would your blood boil?” … “I assume the planets get progressively colder as they get further from the sun.” … “I don’t know. But I think your blood would boil.”

Here’s a gem, 42. “The Little Ghost”:

She’s like I used to be,

so quiet and good.

She waits for me.

She wants to tell me things.

Later on, farther through the book, we get a sense of what this dream could be, and things become clearer:

I actually had a coke dream last night. I used to have them a lot, now not too often. They’re awful. Typically, I’m snorting it off the floor, off a really filthy rug or something, which I never even did in life. But the dreams really bring it back: how you just don’t care. About anything. And how, as soon as you start, you’re already in a bad mood and all you want is more. After a while, it wasn’t even exactly about the high for me. I mainly wanted the feeling of it burning up my nose into my head.

She finally wonders, eluding herself because of her “sister,” who continues to make appearances throughout the book, “Are we free from this fragrance?” Apparently, the “sister” is

a doll. She can’t talk. It’s like talking to a ghost, in a way. I mean, ghosts can’t really talk to you, they don’t exist.

—You’ve had experiences, though, haven’t you? With things that don’t exist, or figures that appeared…?

—I have. And I don’t know what that means. I have no idea. I used to believe in things more.

This book, which weaves deliciously through pages and pages of story and (I wonder) “height,” makes it, finally, to its end. And here we have the way Greenstreet wants to end her collection of small stories:

That’s my other life following me. Woman driving a pale green pickup, hood secured with a length of chain. Two little kids sitting with her. No front plates, mirrors built out from the sides. Her elbow resting in the open window, beaded necklaces swinging from the rearview—two strands, pink and blue. I think she’s singing. Can’t tell if she wants to pass. This is her chance.

These poems in The End of Something pick up where others of Greenstreet’s books leave off, and they create the sense of an ending of youth, of early life, and perhaps of twinhood. Much of Greenstreet’s other work is centered in her voicings, in her ability to weave magical places where one might want to live, but this book seems to lament, through all its pages, the death of that magic.

*

I find Greenstreet’s work always riveting and truly conversational, and this book is no different. The End of Something weaves a tale that we’ve not quite heard before, and it does it beautifully. If you’ve got the inkling to read something that is both quietly on fire and subtly critical, then you won’t be sorry if you go with this book.