Three Jawns: Wolkers, Wild, Wild Country, & Hamilton

02.04.18

Turkish Delight

Jan Wolkers

Tin House Books

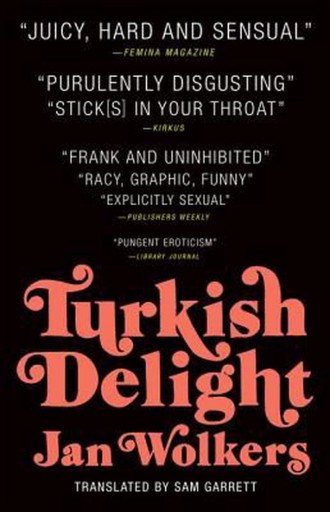

If you want to read something feather-ruffling, you’d do well to explore Turkish Delight, recently re-released as a refreshed translation by Sam Garrett. Penned by Jan Wolkers, a sculptor, the book is a time capsule of Bohemian life in Sweden in the 60s via the marriage and divorce of a man and his muse. The book caused a complete scandal upon release in 1969 due to its sexually explicit content.

This new release asks whether the book still shocks and it does. Opening with the narrator’s lustful attempts to forget his wife mid-divorce, there are notes of Bukowski on some pages, enough to make some readers shake their heads.

But Wolkers is more complex than that — the relationship between the two isn’t flat and it doesn’t stay still. The portrayal of women — namely that of his wife, Olga — can certainly be problematic. And there are valid concerns about portrayals of toxic masculinity in a time when we’re working toward narratives that are more inclusive. In short, these are important conversations to have about work such as this one.

But I would argue that the Guardian’s review, which basically labels Wolkers as a rapist — based on what has been released as a fictional book — takes that viewpoint a bit too far, and into a place where art perhaps can no longer exist outside of the artist. The book is fiction — and it is well-crafted, wild, feral. What begins as a meditation on sex as escape turns into a story of lost love, cancer, and death that crushes the reader in the final pages. While there isn’t even a hint of self-awareness to Bukowski’s bar stool misogyny, Wolkers offers an ending that feels like the beginning of a redemption – or at least creates a gray area similar to Cormac McCarthy’s ending in Child Of God. If Bukowski’s characters are static, Wolkers at least offers us something dynamic.

Certainly, Wolkers’ portrayal of Olga is in line with a Lolita – she is alternately angelic and demonic at turns under his view. And certainly, most of us are sick of the male gaze narrative that makes an object of women — I am. Yet, I find myself still defending this book because of what it accomplishes — which is frustrating, and strange. It begs the question: Is Wolkers an exception? And if so, to what rule?

Reading Wolkers recalls a time when writers were bold, crass, and facing down life and death with a pulse that you could feel through the page. They weren’t always right, kind, or morally just. But it’s a book you won’t be able to put down, a book you’ll want to talk about over drinks instead of online – and it offers an ending that will reverberate through your chest.

Wild, Wild Country

Netflix Documentary

Directors: Chapman Way, Maclain Way

In this six-episode docu-series, the Way brothers unravel the bizarre tale of a spiritual leader from India who moves his followers to a remote Oregon town in the dead of night.

From there, the controversy that surrounds Indian guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, and his personal secretary, Ma Anand Sheela, grows. The Bhagwan is a bit remote as a leader — at first, he speaks openly and freely, but eventually he takes a vow of silence that empowers Sheela to run the show.

At first, everything is idyllic — and it’s quite amazing to see the commune members build their own city with its own electricity, dams, pizza shop, and boutique.

But the people of the nearby tiny town of Antelope, Oregon have suspicious reactions to the new commune being built among their ranches — and tensions quickly rise between men in cowboy hats and the red-clad commune followers. Soon, conflicts within the commune arise, including a power struggle between Sheela and anyone who gets too close to the Bhagwan.

This series shines because of the quality of the interviews, and the artistic eye of the Ways. Sheela is interviewed from an undisclosed location in Switzerland, while other members of the commune speak from their homes. These first-hand accounts open a portal to another time, to a few years when commune members genuinely believed in something larger than themselves.

There’s an ominous tone woven throughout the series – the commune is constantly under scrutiny, both by the press and the police, and eventually Sheela arms the place to the teeth with enough guns to outshoot every cop in Oregon. By the end, no one gets out unscathed — and you’re left questioning the love the commune members felt for their leaders, as well as the motives of the townspeople who reject their new neighbors with sentiments that feel far too familiar in the era of Trump.

But for a few moments in the footage, for a few scenes, it is beautiful to see absolute joy in the faces of the Rajneeshees as they build their commune. They smile brightly as they drive bulldozers, chat as they serve food, laugh as they clean toilets.

It’s easy to make a blanket statement against all religions and spiritual movements — surely, they can be and often are parasitic, cult-like, schemes that draw in people who don’t feel they fit in or belong. Life on the Rajneesh commune couldn’t have been all love and laughter among the wiretapping and poison schemes. But I ended up feeling torn between viewing their love of the Rajneesh as a drug — and being jealous of their brief moments building a life outside of jobs, bills, and big cities.

And it is stranger, still, to see the former Rajneeshees sobbing when they recall that time on the commune when they felt totally loved and totally free. And if we suspend our incredulousness, if we trust their joy, if we ignore the strange leader, the murder attempts and poison, for a brief moment, an entirely different way of living flashes before us like the blue flare on a moonstone.

at hand

Ann Hamilton

Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden

I wasn’t supposed to write about Ann Hamilton. I was at the Hirshhorn Museum for a press opening for a different exhibit, but my friend and I crept up to the third floor, and there she was.

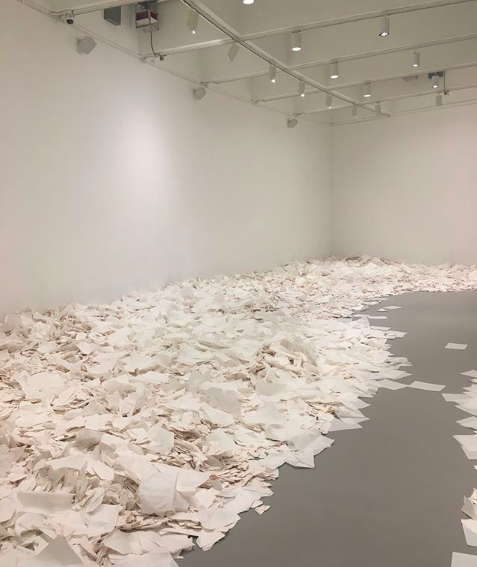

The room was all white, the floor covered in transparent sheets of paper that piled up in small mountains. A voice was murmuring over the speakers, the voice of Ann herself, whispering among the paper.

I heard a whirring sound and looked up. Hanging from the ceiling were machines that suctioned one piece of paper at a time from a stack, then slid them out into the air so they could fall down over us, then pile up around our ankles.

Usually, when I love a piece of art, something cracks in my chest a little — I see it and I light up, I have to puzzle it out, investigate. In the room piled with paper, though, I felt a cold beauty — it was approaching warmth, but mechanically.

I let a few more pieces fall and willed myself to be moved – but instead, I felt only half-lit.

Next to the exhibit was a note that spoke to that coldness:

at hand speaks to the decline of manual labor in the wake of technological innovation. Though the paper accrues on the gallery floor in a sculptural “drift,” the effect of the installation remains one of loss and absence; the paper is blank, the movement is random, and the hand of the artist remains invisible.

Ultimately, the paper was most moving in the air – in the moments between the machines and the ground. Without the artist’s hand, made by machines, the beauty could only last for so long.