“The Camera is for Someone Who Didn’t Bother to Be There”: Talking Art and Rock with Sarah Paul of Glass Traps

29.03.18

It’s the record release show for the self-titled, debut album by new Cleveland post-punk outfit Glass Traps at Cleveland’s Now That’s Class, a cool nihilistic punk bar that recently celebrated its eleventh anniversary. It’s dark and crowded by the time Glass Traps takes the stage, blanketed in a noisy video projection—drums and bass in the back, a guitar on each flank, and, out front, their mysterious singer, a tall, strong woman with short hair, dressed in black, wearing a minimalistic green-blue headband that adds just a touch of glam to the goth.

They open with the first track on their album, “Cold Cut,” and it sounds just like you’d think, given the title: restless, relentless, and dour. The song grows into a march from a stuttering, glitchy guitar, from out of which an ascending bassline lays the groundwork for the doubling guitars to build a wall. And then, the singer begins. Her chorus goes, in part: “Cold, cold cut / But you’re normal, but you’re normal / Off the rails.” Her delivery definitely privileges the sonic over the phonic, and only occasionally does her song coalesce into intelligible words—that’s not a flaw, that’s a feature. The music remains suspended in its sense, its emotional stakes intensely heightened, but ultimately ambiguous. It draws you in.

I move up front and end up behind a photographer. He takes his pictures mechanically, twisting his wrist in a certain, stylized way with every snap he takes, and doesn’t seem to ever look at his camera at all. The singer, for her part, pays no mind to the flickering. She remains closed off, unassailable, and aggressive in her presence, despite being nearly motionless—a cipher barely illuminated by the club lights.

“I cannot stand photographers at shows,” the singer, Sarah Paul, tells me days later at the huge loft space that does double-duty as home and studio. “Throughout the entire set, you have a couple people right in front, in between me and the people I’m performing for. And maybe it’s because I’m interested in live art, but I don’t like cameras—the camera is for someone who didn’t bother to be there. It’s for someplace else.”

By day, Paul is a multimedia artist and performer, working as an associate professor at the Cleveland Institute of Art, where she is Chair of Sculpture and Expanded Media. She’s exhibited and performed extensively, and produced a wide variety of work—video, performance, photos, installations, and the creation of the persona of Little Miss Cleveland, in whose guise she has created a whole sub-universe of art; Little Miss Cleveland has her own videos, her own band, her own pin-up calendar, even (“Celebrate the ghost of Cleveland’s eternally reigning beauty queen every day of the year with this hot 2011 pin-up calendar,” says her website, “featuring 12 months of the most luscious vistas in all The Land.”).

Though Paul is clear that she considers her music to be separate from her work in the art world, in ways ranging from the practical to the philosophical, it’s also clear that music finds it ways into much of her work.

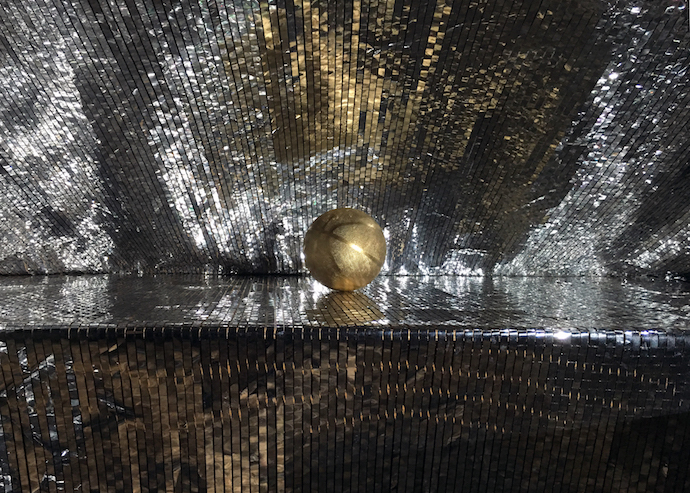

Golden Balls, 2017 from Sarah Paul on Vimeo.

In “Golden Balls,” for instance, a 2017 video by Paul, we see her in her guise as Little Miss Cleveland—wig, makeup, sparkly dress, a beauty queen’s sash—using her phone to record her image in a stretched out expanse of reflective mylar (one of Paul’s favorite materials to work with, it creates fascinating, psychedelic, digital-seeming textures as it’s filmed rippling in the wind) that distorts her reflection as the mylar is manipulated. The scene is accompanied by music, also composed by Paul, that starts as a slow-motion smear of synthy sadness and a spare, forlorn vocal. We see a weave of mylar, dripping with rain in the green countryside. Gradually, the element of noise gives way to a choral segment, in which Paul’s voice, in twin lines, harmonizes with itself, as Little Miss Cleveland, wearing flippers, swims in Lake Erie, the mylar wrapped around her limbs like seaweed. We see the titular golden ball—a basketball, painted gold—under a canopy of the shiny material, lit to glow and sparkle. The sequence of images continues, acquiring a sense of sorrow that grows beyond the close-up, intimate framing of most of these shots, helped in no small part by Paul’s haunting, elegiac soundtrack.

In another video, “Little Miss Cleveland Approved Message #4” from 2016, Miss Cleveland is a raunchier, less sentimental character, still fiercely radiant in appearance, but not as vulnerable as she appears from the bottom of the screen between two men, visible from the ankle to the waist, their bare butts framed by jockstraps as they spank each other. Little Miss Cleveland mutters, but this is a silent piece, so she is mute. Subtitles appear: “Trump smells crazy.” And then, a notice—”Little Miss Cleveland Approved This Message.”

The subtitling in this video evokes one of Paul’s recent epiphanies. While preparing subtitles for another video, one of herself, speaking, that she intended to use in an upcoming performance, she realized that she didn’t have to type in exactly the words she’d said in the recording. She had a swathe of unused footage of Little Miss Cleveland, projects that had never seen the light of day, and she realized that, with new subtitles, she could simply put new words into her pre-recorded mouth. “I can use everything,” she says with satisfaction. “Everything that I’ve ever shot.”

The same is also true of footage that she hasn’t shot, it turns out, but that she’s found; as is the case in her video series, “Slow Grease,” in which Paul treats scenes from Grease with a dramatic slow-motion effect while simultaneously removing their audio. The results find the beloved musical sapped of its verve, its pace reduced to a surreal torpor as each frame of frenetic dancing and romancing is isolated and laid bare. Though Paul’s intervention is rather simple in concept, the effect is disorienting, and sometimes even excruciating, to watch, requiring a near-inhuman patience to properly appreciate.

“I am positive that was a response to being on morphine for months,” Paul says, referring to an accident she suffered in 2013, while preparing an installation for exhibition in a warehouse space in Buffalo, New York. Both of Paul’s legs were broken very badly when a 20-foot I-beam fell over and crushed them. She was hospitalized for a month, and then lived in her father’s drawing studio for the next few months after that, confined to a rented hospital bed while her family cared for her. “I needed everything to slow way down in order to follow anything. Lying on my back for months in so much pain I learned to dissociate incredibly effectively…but to a point where I had a great deal of trouble reining myself back into my body and mind in a way.” It took her a very long time to fully recover from her injuries, and a long time too before she felt capable of and interested in making art again. “I’m still full of metal implants,” she adds, “But I’m strong and pretty well healed…though there will be pain forever.”

In truth, her current recombinatory, adaptive method of composition isn’t new to Paul; she’s kept recordings of her musical output since the ’90s, across three decades of distinct bands and projects. “[I’m like] a digital packrat,” she says, “and [have] just gigs and gigs and gigs and gigs and gigs of sound files and samples and video footage—and all this stuff without necessarily a concrete plan, or a final end.”

The beginnings of her archive date back to around 1989, a year that found Paul at a critical juncture, having just dropped out of college as a freshman at 17. “College crushed me,” she explains. “I went to a really tiny, conservative, rich school, called St. Lawrence University, on a big scholarship. I found so much of what was going on around me offensive and disturbing. I was sexually assaulted several times…it was the stereotypical drunk fraternity scenario. I joined the Student Left, which met around a single table at a coffee house, [while] the Young Republicans had to reserve the huge school auditorium for their meetings.”

Soon after, Paul had joined the band Terror Cake, a rock/metal outfit in upstate New York, and became their lead vocalist. “The band was kind of metal hardcore. They asked me to sing, and I was like, ‘Sing in a rock band?’ and I told them that if they learned Blondie’s ‘Dreaming’ then we could see how it worked. They gave me a shitty cassette recording of the song ‘Oozing Rhyme’ to try to write vocals over. I went and wrote my first vocal melody and lyrics and never looked back, really. It blew my mind and liberated me in such a massive way.”

As a female-fronted heavy band, Terror Cake was a rarity in the area, and, in Paul’s words, “The response we got from young women in particular made me realize the potential power in my voice and stage presence. As a talented young person, I was told over and over that I couldn’t be given the lead female roles in our school plays because I was too tall, despite acknowledgment that I had the strongest voice for a given part,” she says. “Upon joining Terror Cake, I cut my hair off, dyed it orange, and donned combat boots and thrift store sport coats. It wasn’t a well-groomed anti-establishment look…I was not good enough with fashion or make-up for that. It was just sloppy and crude. And apparently not very marketable. The pattern of having comments and suggestions about my portrayal of femininity was quickly obvious to me, but I didn’t really associate it with my experience in theater as a young person until I [later] started making art that explored gender identity and fluidity. I felt confused and insecure and angry.”

Thus, when Terror Cake broke up in 1995, Paul forged ahead with music on her own, producing and recording in solitude. After a stint with another band, Jump Cannon, in which she received further pushback against her style, Paul realized that she would have “more freedom and funding if [she] pulled [her] musical performance and experimentation into a fine art context.” Paul finished her BS in Mathematics, which had been on hold for a few years, and in 2005 began work on her MFA at the University of Buffalo. The transition would prove to be a difficult period for Paul, one that changed the whole direction of her life and art.

“I’m kind of shocked I survived my 20s,” Paul says. “They were pretty dark and clouded with drugs, mental illness, and reckless behavior. I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in my teens and survived an attempted overdose at 16. I didn’t really stabilize mentally, whatever that means, until my 30s, when I began to be treated for a sleep disorder as well. Some people say [insomnia] makes for fertile creativity and all, but I don’t think it helped me most of the time…I was in so much pain mentally and so exhausted I couldn’t focus.”

Paul finally learned to truly embrace her recombinant style of process of production from Tony Conrad, one of her mentors at the University of Buffalo, along with the artist Steve Kurtz. “Something I’ve struggled with since Tony died a couple years ago,” she says, “was how much I’ve used pop music in my work…and I wonder if he thought less of me because of it. I imagine he must have, though he never hinted at it. We had practically diametrically opposed views about pop melody. He campaigned against the hook-laden chords of western music and all I want to do is write ear worms that people can’t get out of their heads.”

“He made me cry a couple times,” she continues. “Once he called me a show off. Which at first crushed me till I realized he was one of the biggest show offs I was spending time with. His influence for me is most clear in the way I work. When I met and worked with him I saw that he too was a packrat of sound and video especially…and that recordings made decades prior could come back around to be repurposed in new contexts.”

After graduation, Paul moved to Cleveland, where she began work at the Cleveland Institute of Art and, in 2009, met Matt Hallaran, a musician who, at the time, lived just down the hall from Paul’s apartment. The two became fast friends. “We began having nightly jam sessions…putting headphones on and doing improvised electro noise pop into my computer for hours. He’s playing all of the electronics and I’m singing gibberish through guitar pedals.” Years later, Hallaran would ask Paul to record a vocal for a song written by a new band, for which he played the guitar. That song ended up being “Eiffel,” and that band, Glass Traps, a collaboration in which Paul found her contributions finally respected.

The band’s self-titled debut is an excellent showcase for their sound. Though their reference points may seem obvious—Paul mentions that, forced to produce RIYL comparisons for publicity purposes, she’s come up with Siouxsie and the Banshees and Magazine for more historical points of reference, and Total Control, Savages, and fellow Cleveland deathrockers Pleasure Leftists for comparable contemporaries—Glass Traps are not easily reduced to their influences. Right away, the gorgeous album artwork by artist Kristina Kuhn, frames Glass Traps as something a bit unusual, depicting razor sharp, black-and-white architecture against a psychedelic sunset. The music matches its packaging, too, dealing in grand, but somewhat obscure, emotional gestures that reveal a rabbit hole of rewarding details on repeat listens. The band trades in post-punk’s usual focus on the rhythm section for a concerted exploration of dual-guitar riff space and a healthy surplus of melody. The album covers a considerable amount of tonal territory in its 27-minute runtime, from the haunting dirge of “Cold Cut,” to the dreamy pop of “Eiffel,” from the careening rock of “Kowloon Wallet” to the spacious, menacing crawl of album closer “Obron.” The rhythm section of Sebastian Wagner on bass and Steve Crobar on drums takes a no-nonsense approach, propelling each song relentlessly forward and conjuring up a cavernous sonic space in which guitarists Chuck Cieslik and Matt Hallaran keep plenty busy, laying down shifting patterns and interlocking leads. Paul’s gloomy vocals sit low in the mix, for this sort of music, positioning her among, rather than in front of, the instrumentals, and the decision suits the music well.

Even at its most complex, the guitar/vocal dynamic is complementary, not competitive—check out the beginning of the anthemic “Rot In A Field,” for instance, in which an intricate guitar lines embraces Paul’s simple, soaring melody to create an exhilarating, romantic hook, or the verses of “Freight Elevator,” where Paul holds down a controlled monotone reverie as the guitars quest for release around her. Paul’s voice is the band’s not-so-secret weapon, coloring the accompanying music in a dozen different shades ranging from dour to swaggering to downright triumphant. Their take on their genre is consistently inventive and wrings new life out of post-punk’s apparently inexhaustible recesses.

And for Paul, Glass Traps is a perfect balance between her solitary sensibility and her desire for group collaboration. The music is meant for the stage, for the holes-in-the-wall, not for the walls of a gallery or the anonymous non-place of the internet. Her music is free to travel in ways that her art is not, and it gives Paul a whole new industry apparatus to master—a challenge she seems to relish. And her fellow bandmates don’t give her grief for her unique vocal abilities or her performative sensibility, a freedom that comes through in the work. “They love it if I sing some weird low croony thing that definitely sounds like a dude, it just doesn’t faze them whatsoever. They’re like, ‘the weirder, the better.’ It’s great.” And it is. Great, and urgently necessary.

—————-

All images by Sarah Paul except Glass Traps live image by Kevin McCann.