The Prison & The Idiot: Arnaud Théval Photographs France’s Abandoned Jails

08.01.18

Arnaud Théval sat in a garden in Bordeaux, France, explaining his latest project to me in a thick French accent.

“Prisons?” I said.

“Yes, yes,” he explained. “I take photographs of prisons in the hour after they are closed. Once the inmates are transferred to the new prison, I take pictures of the old one.”

Already, a strange scenario: A new, shining prison built outside of the city, and inmates transferred there — the old prison left to rot.

Someone brought his book, La Prison & L’Idiot, out of the house, and I cracked it open on my lap.

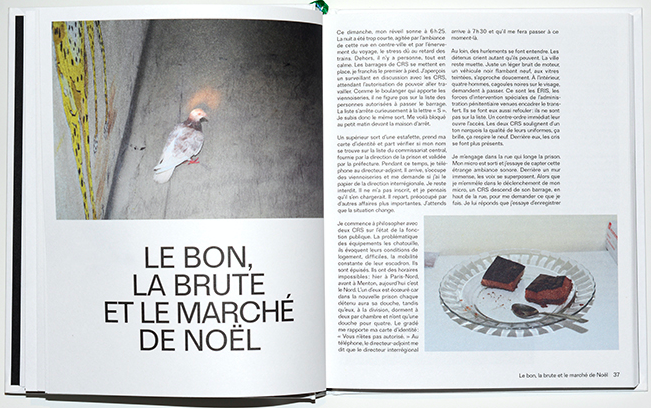

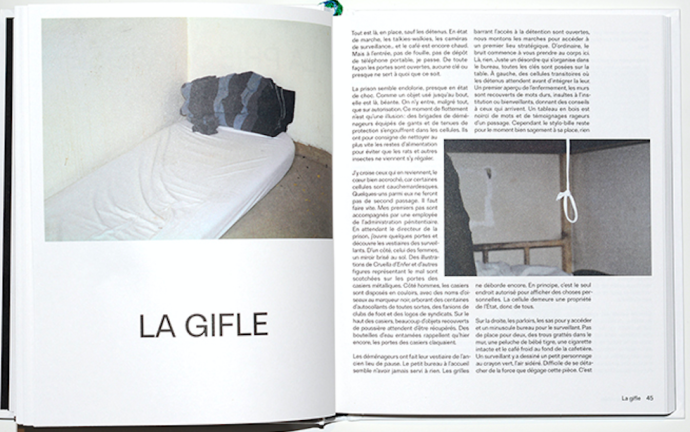

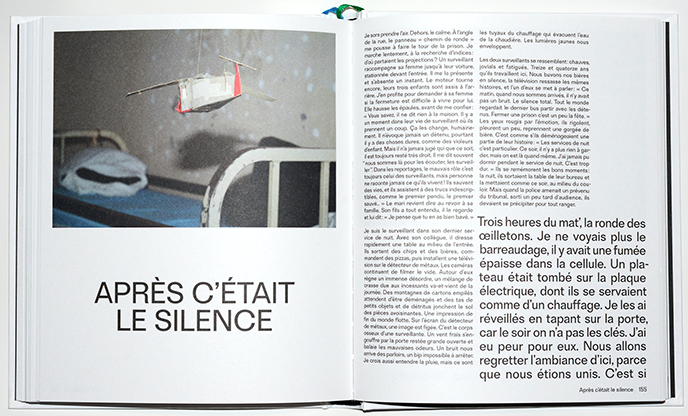

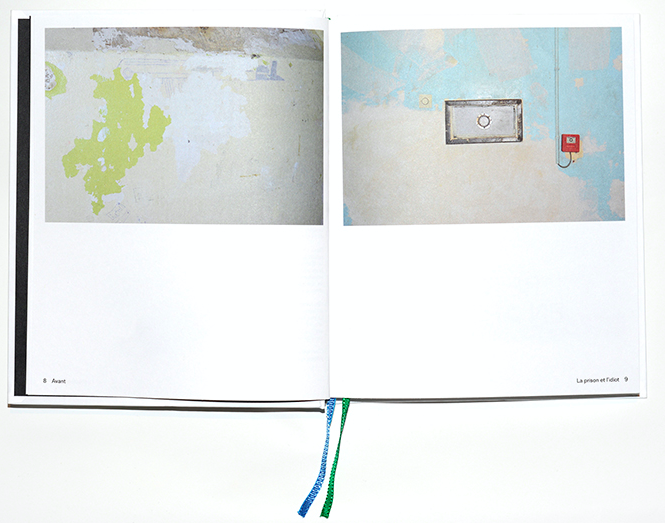

The photographs were textured, abandoned, but still alive — bits of the lives of inmates remained, their favorite sexy photos taped to walls, the empty, stained containers of their final meals in that prison. The book was also full of French text, written by Théval as he took the photographs, capturing his feelings and emotions within the prison walls.

The project, like prison itself, is complicated.

I’ve spent years reporting on prison conditions in America, and it’s a nuanced issue. I struggled to balance my empathy with the wrongly imprisoned suffering inhumane conditions with the job of the prison guards who kept them in line — sometimes abusing power, and other times seeming helplessly trapped in the cycle of a job that paid well and required them to enforce the rules, sometimes violently.

In the United States, the prison industrial complex presents what amounts to a financial reason to continue to grow prisons — and increase the inmate population, largely by incarcerating minorities at disproportionate rates — to keep business booming.

At the end of 2011, approximately seven million people were under “some form of correctional control.” Last I checked, the prison industry was the second largest industry in America — beat out only by Hollywood. To put some context to the size of this industry, consider this: Private prisons were a $4.8 billion industry in 2015, with profits of $629 million according to market research firm Ibis.

Simply put, new jails in America signify more space to arrest more people — and enough revenue to build a new facility. And beneath all of that money, all of those “new jobs,” and “growth,” is an engine: It’s all supported by the disproportionate jailing of minorities.

According to the NAACP, African Americans constituted 2.3 million, or 34%, of the total 6.8 million correctional population in 2014. That means African Americans were incarcerated at more than 5 times the rate of whites. Those numbers only get more glum when we look at other minority communities.

I say all of this to say that France’s prison system is not a direct one-to-one corollary to the United States. Issues in the French prison system are familiar – those of overcrowding, understaffing, and persistent claims of inhumane treatment. In addition, French prisons can be semi-private, leveraging prison management companies to manage certain functions of the prison – which does hint at some profit being made.

But as far as populations go, recent research from World Prison Brief indicates France saw years of steady prison population growth — although the number of those incarcerated in France is far lower at 68, 574. There are also conflicting reports about the number of Muslim-identifying inmates in French prisons – some reports say 70% of all inmates are Muslim or Muslim-identifying, other researchers find the number closer to 50%. The French government doesn’t track that statistic, so it’s harder to tell whether the issue of disproportionately arresting minorities correlates.

Théval’s project put him in close contact with prison guards, which enabled him to take photographs. And while I’m interested in the project, the photographs, and even to some extent the relationship between Théval and the prison itself, as well as its guards, there is something about the photographs that makes me sad.

The project begs a question: What is important to document? What do we find by looking at what’s left behind from any life – be it one in a prison or one outside of one? How does capturing these moments bring us closer to those not in the photograph?

I spoke with Théval about the book which is a huge success in France, how it came about, and his relationship to French prison. This interview has been graciously translated for us by Florianne Segalowitch.

SARAH ROSE ETTER: What inspired you to choose prisons as your subject matter? How did this project come about?

ARNAUD THÈVAL: I walked by the walls of the prison from age 13 to 19, every day. It was just another local building. Five years after I graduated from art school, I had the opportunity to lead a creative photography workshop with the inmates there.

A memory stuck. We walked up the old wooden stairs in the administration building of the detention center. The dust would glisten and dance in the warm light The city was gradually revealing itself as we were going up: the police station, courthouse, and some tall Haussmann-style buildings neighboring the prison. I was following Anne-Sophie, a probation officer and my guide for the occasion – my hands were sweaty.

Despite the doors slamming, the stuffy air, the noise of shoes shuffling on the floor, the waxy faces of the inmates, and the familiar laughs of the guards, things were going well.

The inmates and I kept walking around the prison, disposable cameras in hand. Then we had to get the cameras out, develop the films, have the pictures controlled by the deputy director of the prison, and make the collage compositions. I had the pictures printed as postcards – some of which were given to prison guards by the inmates – and I left. These scènes de voyages were the evocations of an imaginary trip to an ideal place. The workshop took place in a small room. I could hear prison life, but not see it. I met people from within, ordinary people. It is stunning to find oneself suddenly deprived of their freedom to move unrestrictedly.

The notion of being locked-in has since then been central to my artistic process – I have worked with two public institutions: a school and a hospital. Prison was for me an entity that swallows and spits back random people, an absent object. A tangible architectural being, but faraway, like a barely audible sound.

It took another trigger to unbury this idea: a short article in a local newspaper in early 2011. A new prison building would soon be in operation, putting an end to the use of the old downtown prison. I felt the urge to acquaint myself with this place before society wiped it off from my memory.

These old 19th century prisons were swallowed up by spreading city centers until they became part of the cityscape… but now new prisons are built in suburbs or in the depths of the countryside. This is a turning point for French prisons, both in terms of organization and social status. Since then, I’ve kept myself immersed the penitentiary culture, starting off with this observation: the end of an era.

SRE: How did you get into the prisons? And why did you choose to take pictures of the spaces an hour after they were closed?

AT: When I come into the prison, it is an hour after it has closed down. The inmates’ transfer from one prison to another is barely finished. The prison staff is worn out, and either gives up or works twice as much to clean up the mess. Official photographers pack up their gear, journalists have finished their articles and riot police officers head back to their quarters. This is when I chose to enter the prison. There are no more locks on doors, and the dust and wind are settling in. But for a few more hours, Life still inhabits the vicinity. After a few moments of amazement I start engaging, and recreate step by step the phases of imprisonment.

I try to recreate this new place, where I have lived neither as a convict nor a guard. My mind is yet filled with images. My photos feel like silent memories that later blow up in my face, when the guards put words on them. Prison is rarely a tale told by those who work there. And when a prison closes down, this when I chose to look through the other side of the peephole.

My experience comes from the shutting down of three prisons and several years immersed in penitentiary culture. I get around the direct confrontation to imprisonment and avoid having to comply to strict penitentiary rules. My work is never commissioned either.

Between these dirty walls, I move carefully, like an archeologist. I wear myself out archiving this living heritage, to the point of photographing tiny derelict objects. This is where you find the violence and beauty of the inmate-guard relationship, somewhere between the society and this cul-de-sac.

These few after-moments still hold for a while the essence of imprisonment. The few hours when the prison still remains a prison will pass by with increased velocity: the day after it will no longer be a prison.

In this restlessness, while the smells are still strong, the coffee cup not quite empty yet, the unmade beds still holding the shape of invisible bodies, I face the signs that shaped this place.

Authority is constantly put to the test. Convicts try to find new routes of circulation, to acquire more space, and the wardens must hold the power by plugging off these holes that would put safety at stake. This is the symmetrical system – either overthrowing surveillance or ensuring its viability – that you uncover gradually. Like this drawing of a tiger jumping on a butterfly, the balance of power constantly re-assessed, until either side wears out first. This is the unpredictable, vacillating prison dynamics I have been contemplating, as an idiot onlooker.

SRE: What did you find that surprised you over the course of this project?

AT: I felt very affected by the vulnerability expressed by the prison guards, and by the permeability of these places of detention. There is a constant dialogue between one another’s fears and worries. Using the relationship to the prison guard to immerse myself in this space felt like discovering a new continent. We usually turn a blind eye on this universe, as it feels embarrassing almost to reflect on what these people go through – they themselves are reluctant to share their experience: what comes out first is usually the ongoing violence, a violence that seeps through everything and is ever-present in their vocabulary.

But these words are like a shell, they prevent the other aspects of prison life from uprising. Maybe because they feel ashamed, or because it sheds too much light on the complex relationships between a guard and an inmate. What surprises me the most might very well be the attempt of miniaturization of the society as a whole in these places of detention; it impregnates the most those whose responsibility is to lock up those doors.

All of this makes it almost impossible to talk about prison in any other way… Art as a medium is ideal as it is, in the words of Michel Foucault, an heterotopia, where our imagination can be active, where we can collect testimonials, ideas, and turn them into something else in these places usually stuck in their beliefs! The guards and wardens were happy to talk about their experience. As I come with no bias, we would quickly establish a trusting relationship for them to share their memories.

SRE: The writing within the book is personal from what you’ve shared with me. Can you tell me a little bit more about how and when you wrote versus how and when you took the photographs?

AT: I wrote and photographed at the same time. I would photograph in the daytime until complete exhaustion, and afterward I would note down what I was going through, like a catharsis. These photographs could only hold a fragment of my feelings, they said nothing of my questionings. I would photograph as if everything was to disappear in the following minutes, like I was facing a treasure, these life fragments still intact, wet, sticky but alive. I chose to photograph head-on, to neutralize wide angles as to keep fragments only… to keep myself separate from the spectacular aspect and from the obvious violence of such place.

This was the hardest thing to do. Our society feasts on this kind of voyeurism, but I don’t. That’s the necessary distance for reserve, to be able to look under the fresh rubble to find something else – and this I could not do alone. Meeting these people and writing things down helped me find this distance, yet, I was using « I » all along. Writing felt like a new urgency in my work, that had accompanied me for long but that arose to the same level as photography for the first time.

As I was exploring these barely empty prisons, I started to see. The stories told by the guard were so strong they helped me make sense of these places, find hints of their relationships with the convicts, understand the convicts themselves with their life stories and the mere shadows of their lives in prison. As I was working through my visual memory, words would arise. It’s almost the first draft, barely edited, like breathing in after being underwater for a while. I’ve never stopped writing this way since experimenting this urgency to write what I was living in this empty prison – my penitentiary trauma. It was a real trigger. Something shifted in my relationship to other people, their life stories, their private geographies.

SRE: Do you think this project has changed how you see prisons in France? What new perspectives might you have on prisoners after this project?

AT: I now understand how endlessly complex prisons are, and how essential it is to make them a central question in our society, instead of casting them off on the outskirts.

But to succeed, we must change the way we look at them. Art can be a good lever and can trigger discussions. This is what art does, it can induce tiny short-circuits at the heart of the system to change it. That does not depreciate the value of art for art’s sake, these approaches should be reconciled, not opposed!

Prison is the dead-end of our thoughts, a banishment that feels like a failure, and the confession of a single solution for reductive thoughts. It is a reflection of our society, radicalizing itself from all parts, a society that won’t give means to try out other policies. we need to establish other relationships with its partakers, to collectively take hold of this space again.

I will first be developing my projects around the judiciary institutions (magistrates and their abilities to lock away or set free). I will then try to delve further into the guard-inmate relationships — try to find out what is at stake, other than violence. These relationships obviously exist, but are we willing to name, describe and share them, in a society so eager to witness punishment on display?