The Empty Sarcophagus: ANDREW WESSELS IN CONVERSATION WITH VI KHI NAO

04.01.18

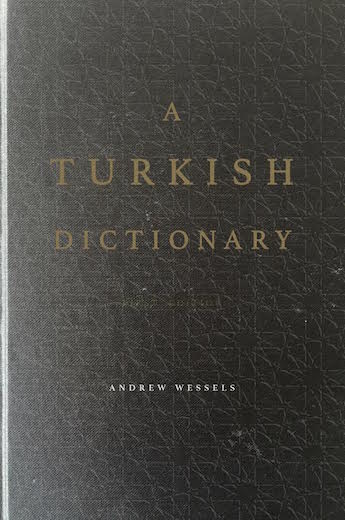

Andrew Wessels is a poet, translator, editor, teacher, and book designer. His poetry collection, A Turkish Dictionary, came out into the world from Press 1913 early this year. This is to say that both Andrew Wessels and I are pressmates. I had a wonderful opportunity to conduct a time-based interview with him while he was visiting Turkey with his wife while I was in Vegas. In this interview, Andrew Wessels spoke about Isbanbul, being a translator, falling in love with Ece Ayhan, and about slow cooking a book into being. Our conversation is full of vitality and relish. – VKN

VI KHI NAO: You are in Istanbul and I am somewhere near Sin City. It’s morning for you and it’s evening for me. Have you made many trips back to Turkey since the coup? What is the air like where you are? Did you sleep well? I have a note somewhere that recalls the last time you were there you were in an apartment with the view of Bosporus. What is your view like now?

ANDREW WESSELS: This is my first time traveling back to Istanbul since moving back to Los Angeles in January of this year. I spent the fall in Istanbul after the coup, and left following the end of the fall semester. The air right now is cool and crisp, as fall has begun while I’m here. It’s lightly raining outside this morning. I didn’t sleep well because I was out with friends for a nearly-final night on this trip. We went to a meyhane, which is a traditional Turkish restaurant for a good evening out. We sat together for hours eating, drinking, talking. At this moment, I don’t have a view because I’m inside, but I’m staying with my in-laws who have a partial view of the Marmara Sea. I miss the view from my old apartment; I’ve kept a photo of the view as the background of my phone.

VKN: Your wife’s name is Zeliha, yes? Does your love for your wife shape your poetry and devotion for the language Turkey and its place? Has your wife contributed to your love of it or did it arrive to you before you were born? And, what did you eat at the restaurant?

AW: The meyhane meal is a long, multi-course shared meal. We started with a selection of cold mezes, or cold appetizers on shared plates, such as sea bass in pesto, a red pepper paste (ezme), an eggplant dish, a yogurt dish, and others. Then hot mezes, then we had shrimp and calamari. Throughout the meal, we drank rakı, the national liquor here. Zel is definitely an inspiration for my love of Istanbul and Turkey. I first traveled to Istanbul 10 years ago, a few months before Zel and I met. So my interest in the city and country began blossoming before, but being with her has nourished it beyond. In part, my interest is in growing our life and home together and trying to find and build a space that we share together. And in part, it’s a pull that I can’t explain that can only be love of her and love of here.

VKN: What was Istanbul like 10 years ago? Did your translation of the work of Nurduran Duman invite you there?

AW: I started translating a few years after I first visited. I came with my sister. We were traveling together and decided to come to Istanbul, in part at the behest of one of my mentors from college. I knew only distantly and generally about Istanbul at the time. The city has certainly changed in many ways over the decade. The already vast city has grown by several million more residents and several million refugees. Skyscrapers have shot up all over the city. It’s hard to describe the changes completely, though many have in books and think pieces, about the destruction of the old to build the new, about power and land grabs, about corruption, about crackdowns on secularism. I was just thinking about this last night while going back home from the restaurant, how I’ve experienced a decade here, and how the city is still completely recognizable yet so vastly different than what I first encountered.

VKN: I feel some nostalgic sadness in this quiet, drastic shift. Speaking of skyscrapers shooting up, your poetry on page 17 of your A Turkish Dictionary made me think of your meditation on erasure. Erasure here visually appears like a game of tetris, mathematical and linguistic tetris. While I read your poetry collection, I had the physical sense that words were going to fall from the sky of your text and if I didn’t move fast enough, the piles of erasure created by your poetry would end the semantic game for me. Erasure and purging of words and people (people, here, I meant, journalists, dissenters, judges, academics, etc) seem to shape the current and past history of Turkey). Do you feel some of your poetry is prophetic? Or is it just an expression of history repeating itself in different ways?

AW: I think that it’s really an expression of history repeating itself. History–and the powers that shape history–are powers of erasure. But I do think that some of my language means something different now in light of the changes in Turkey and in the larger world than when I wrote it. The refrain “Atatürk, where did they put your words?” was initially meant more in a physical way–where is that speech? Where did those lost words go? But after the coup, after the crackdown, after Trump, after so many things, the meanings have changed. And I do feel as a writer like it’s a game of tetris, trying to find the words and trying to dodge the words simultaneously as an expression of what it’s like to live in this world.

VKN: After the coup, you feared that if your book got in the wrong hands, you could be, like other academics, imprisoned, tortured for your words. Which part of your A Turkish Dictionary or what page you elevated or ignited the most fear for you? Do you feel the urge to tear it out of your book? To preserve, to purge it out of your soul, to protect your family, if it comes to that?

AW: There’s a section in the second part of the book where I quote Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who at the time was Prime Minister and who is now the President of Turkey. The quote is about a statue outside of Kars that angered him, and that he demanded be removed. While I don’t editorialize directly, I think it’s hard to read the section without coming to the conclusion that Erdoğan is a philistine. So, especially given my job there at a major university, I did become concerned that the book could get into the wrong hands and that something could happen. I’m still trying to determine what the actual chances were, and I just really don’t know. People who have been personally affected by the crackdown give me a higher number; people more removed politically give me a lower number. I did consider the idea of taking it out, but I never thought about it as an actual possibility. I have trouble still coming to an understanding of my feelings about the situation, about the ultimate potential effects. Thankfully, at this point, I haven’t been forced to make hard decisions, but I’m trying to be aware that I might have to in the future. And I don’t know how I’ll react. What I think was hardest and strangest about the coup attempt was that when something of that power is happening, there is literally nothing that you can do. You just sit and wait and then see what happens. And what I feel, especially being back here now, is a sadness and deep guilt at my privilege at being able to leave and go elsewhere when so many don’t have that option whether that’s because of the randomness of citizenship and passports or economic means.

VKN: A coup operated almost like a large blanket of fog and one has to just simply wait until the sky and ground are clear before proceeding. I imagine how helpless one must feel to not know and one must prepare to wait. Despite obscene censorship in the media of Turkey and since Turkey is predominantly Islamic, do you feel as a Muslim American, you experience less faith bigotry there? Am I assuming that you are in a place where your faith, though not necessarily your poetry or your voice, is welcomed?

AW: While there are things I worry about more here, that is something I certainly worry about less. I am a straight, white male, so I’m lucky when I’m in the States that I don’t “appear” different, and thus can pass in various situations. But, especially since Trump rose to power, there has been a distinct fear when I’m in the States, when advisors of the President talk about the Internment of Japanese Americans as a legal precedent for the internment of Muslim Americans. One of my wife’s friends was caught in the immediate aftermath of the first travel ban. It is also nice here to hear the call to prayer, which woke me up this morning to get ready for this interview.

VKN: Besides Duman, are there other Turkish poets you would recommend checking out? I love your translation of her work, by the way. Especially the one published in Asymptote.

AW: Thank you! The poet that most people start with is Nazim Hikmet, the great Turkish poet of the first half of the 20th century. His epic poem Human Landscapes from My Country is something everyone should read. The first poet I fell in love with was Ece Ayhan and I’ve spent a fair amount of time reading the era that he was part of, the İkinci Yeni or the Second New, such as İlhan Berk and Cemal Süreya. I also really love the work, both poetry and painting, of Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu. In general, I spend most of my time now for better and worse (when I’m not focused on translating Duman) with some novelists, such as Bilge Karasu, Aslı Erdoğan, Yusuf Atılgan, and Yaşar Kemal.

VKN: Thank you for such a lovely list, Andrew. What about Ece Ayhan that captivated your soul?

AW: Ayhan and the İkinci Yeni in general I think are recognizable to American readers through the New York School. Ayhan in particular could be read comparatively alongside O’Hara, Koch, and Guest. In general, his poems come out of the area of Istanbul where he lived, Beyoğlu, which historically has been a place that housed the gay community, the trans community, and the artistic community. His poems evoke an artistic and self creation occurring on these old streets, in alleys nestled between these tall buildings, in coffee and tea houses, in tiny restaurants. But his poems also evoke this eternal call that permeates beyond any individual time and place, such as the poem I included in the first section of the book. There is a collection of two of his books translated into English by Murat Nemet-Nejat, A Blind Cat Black and Orthodoxies that I think helps represent that vastness in English.

VKN: You wrote “A sarcophagus that contains no bones.” Is it like a book of poetry that contains no word? What would be a better metaphor to reflect the missing ghost of the past?

AW: I think that an empty book of poetry would be similar, but I think maybe every book is similar. I think we oftentimes open a book hoping to find something finalizing–to actually achieve catharsis in some way, whether that’s through being fully entertained if it’s a fun book or reaching some definitive understanding of life if it’s a philosophical book. But that finality is always missing in some way, it’s all perhaps a MacGuffin that we’re seeking. And the hope, or at least the hope that I cling to, is that the journey itself–the journey to find the empty sarcophagus, the journey to find the history, the journey to find the right word–is sufficient.

VKN: It took you eight years to pull your A Turkish Dictionary together, at a meticulously slow rate, intentionally, I assumed, almost like 10 pages per year. Is this your usual desire to exist in the world? Or is it only with poetry? During those eight years that it took you to shape the shifting landscape of your words, what is the one thing you learned through this persevered process? My favorite poem of yours takes place or appears on the last page. May I assume that your poetry collection isn’t created or written chronologically. When and how did this poem arrive to you? I felt great sadness reading it. And, nostalgic and forlorn, in a beautiful way, after reading it. It is one of your simplest poems, but it has the most impact on me.

AW: The book was written semi-chronologically. The first part was the first part, the second part was the second part, and the third part was the third part. At least if we look at the book at a macro-level. But many individual pages within, particularly the dictionary poems, don’t follow that chronology. The book accrued over time, as I returned to Turkey, as Zel and I built our lives together, as I developed as a writer. There was an accumulation that became the book. In general, I do think I work meticulously slow. I wait for things to come, and it takes me a long time to process my thoughts, my feelings, and my understandings. The last page is a true story, as is the larger narrative of the book–what happened the morning after that walk through Istanbul. And it’s to some degree what I did this morning: I woke up in advance of the call to prayer, to prepare myself to hear it. It was my first experience of the city 10 years ago, arriving in the middle of the night, sleeping for an hour or two, then being woken for the first time by the call. And I think I recognized at least a large part of what I was trying to communicate in the book within that moment: the sound, the music, the preparation, the prayer, and the continuation.

VKN: That is very beautiful, Andrew, the way you impart your relationship with the call for prayer. Besides the beauty and sadness of your last poem, another aspect of your dictionary that moved me emotionally and aesthetically is your content page. It reads like a poem in itself. The way it’s formatted and the words you had chosen to study. What selection process did you go through to handpick such a dictionary? Considering that there are thousands of words to choose from.

AW: The Turkish words in the dictionary poems were words that I came across that stuck with me for various reasons. Sometimes I thought the ways that the words spanned different English equivalents was interesting. Sometimes the sounds or word fragments within captured me. Like with other aspects of the book, it was a natural accrual that I didn’t define or control in an active way. I wrote many other dictionary poems beyond what’s included here, which I removed or never added to the collection. The very first dictionary poem I wrote, which initiated the entire book but never was included in the book, came to me while I was walking through my first snow while living for a year in Boston. I knew immediately that it was titled “Ağaç :: Tree”, and it was a short poem about how a tree can be taller than the moon, and how the moon’s spinning is funny. E

VKN: You wrote, “Sit in the shade and drink tea from tulips.” What an aesthetically compelling image. It continues to stay with me after I departed from it several days ago. In continuant of the profound visualization, Will you fill in the following blank. “Sit in the shade and drink politics from ___.?”

AW: Roses.

VKN: It’s usually my standard question to ask if you will break down a poem for us? Where were you when you wrote it? (Would you like me to select one or would you like to?) Will you expound some of the references that may not be obvious to some readers? And, if you did research in order to write it, how did you fumble upon those sources. And, if possible, what were you eating when you wrote it?

AW: “Yok :: Not Existent” was one of the earlier dictionary poems that I wrote, and which became a touchstone I think for the collection. I realized soon that it would be something that the book needed to work toward, that it was conclusive in some way but that it also needed everything to happen before it for non-existence to be possible. The poem’s form, at least in my mind, related to the sounds of the call to prayer as well as other forms I was reading such as the ghazal, the sonnet, the ode, and more generally the concept of the arabesque that recurs through the book. The form that I wrote is none of these, but I think it reacts to the ways that poetic forms manage the tripleness of language’s sound, meaning, and physical presence. The poem itself is this strange image that I had in my head, that I probably didn’t completely or accurately communicate in the poem because it’s likely multiple simultaneous images that only I can see. But I think the opening line is all of it: in the elation. It is what my elation felt like, at least at that time, and how it came to me. I’m not sure if I did any particular research for this poem. When I wrote it, I had recently read Ayhan, Hikmet, and Scalapino. I was in my early months of learning the Turkish language, and language as a whole was feeling othered to me. I had this image that I knew I couldn’t describe sufficiently with language, and I took the raw materials of the image and combined them and recombined them and let adjectives attach to different words and let the form of the poem on the page coalesce into something recognizable and unrecognizable, and I watched the two columns of the poem reach out toward each other, and then I read the words over and over and over again out loud until their sounds made more sense than their meanings. I wish I could remember what I was eating when I wrote it, because I would probably eat that same meal every single day.

VKN: It looks easy, but I think writing ghazal is very hard. I haven’t been able to write one. Do you find it hard? Its shape? Its repetition? What poem of yours appeals to your wife the most? Have you written many love poems, Andrew? Also, this may seem non-sequitur, but what is your favorite mosque in Istanbul? And, what do you love about it? Based on your tour guideship, if I get a chance to visit Turkey, I would be excited to visit it.

AW: I’ve never been able to successfully write any poetic form, at least in the traditional and formal sense. I’ve written many poems that I think move in similar ways to these forms, whether it’s the turn of a sonnet or the refrain of the ghazal. But something in my brain or personality kicks back when I try to impose a structure. So I’m in the same situation as you–I’ve tried many times, and failed consistently. I just asked Zel what her favorite poem is and she gave two answers: either the “Tanışmak/Tanıştırmak” series in the third section or the image that opens the first section of the book with the refrain “The sky is different here.” I think a lot of my poems are love poems, but I’m not sure if they are traditional love poems. I always have trouble writing toward what I want to actually write toward. But the book as a whole is a love poem for Zel and is dedicated to her. The mosque that most people visit first, the Blue Mosque, is something that can’t be described. But to go past the obvious attraction, I love Eyüp Sultan, which is at the top of a hill near the head of the Golden Horn. It’s a small mosque, and one of the first built in Istanbul. It is the supposed burial ground of one of Muhammad’s best friends, and the site was often used during the sultan coronations. I also think it’s worth doing a tour of all of Mimar Sinan’s mosques such as Şehzade and Süleymaniye. I also love Ortaköy Mosque, both for its individual beauty as well as its location jutting out onto the Bosporus.

VKN: Why does she prefer those? Have you read your entire collection outloud, Andrew, to her? Or to yourself? Which poem is the hardest to read outloud? When I read your collection, I tried to imagine what it sounds like in my head. But it became all mushy like an egg in a blender.

AW: In part I think it’s because those are the sections I read the most–her initial answer to me mentioned that act of reading. I’ve never read the entire book aloud in a single sitting, but I have read all of the book out loud at various times during the editing of the book. When I’m giving a reading, the most challenging thing is figuring out how to transition from the more prose pieces to the more lyric pieces, and how to change my delivery. And how to let the sounds and words have clarity while dodging the waterfall of words or the Tetris as you described it above.

VKN: What are you working on right now, Andrew? Do you think the next collection will take you the same amount of time to put together? What do you hope to achieve with it? Or walk away or walk together or walk before with it?

AW: I wrote a second collection when I first moved to Istanbul in 2015. I’d started that project in about 2011, so comparatively this one was faster. But I’m not quite sure that it’s something that I want published or that should be published. I’m deeply unsure about it. I’ve started a new manuscript, or re-started a manuscript that I first began also in about 2011. I fear that one will take at least as long as this first one. The first of these manuscripts is a writing through or against Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene. The second of these is a meditation on places (Istanbul, Los Angeles, London, Houston) and history at least partially through the lens of philosophy of mind and theories of consciousness. That started, years ago, as a book of poetry, but right now what’s happening is a book of prose. I think of this second manuscript more as the next step from A Turkish Dictionary, simultaneously a walking away, together, before, and after it.

VKN: What are some of the techniques you have used to change your delivery? What hasn’t worked?

AW: I’ve done things such as only read from the dictionary poems and ignoring the prose. I’ve read them continuously and without stopping. Lately, I’ve begun treating every page as a very distinct thing, even when series of pages are clearly connected narratively. That approach seems to have worked the best, and it allows me to read the prose pieces in a more literal way and then have a pause that helps transition to a more sound-based reading of the lyric dictionary poems.

VKN: You translated Ayhan’s poem on page 21, yes? What was that process like? Do you feel translation is a way of writing on history or rewriting history? “How much can we store in a single collection of poetry?” If you were forced to choose between being a translator or a poet, which one would you abandon?

AW: Oh that’s a hard question! I see the translation and writing practice as so intertwined that it’s almost impossible now to envision one without the other. I can imagine myself being unable to write–not knowing what I want to do–but I can’t imagine myself being unable to find something that I want to translate or feel the need to translate. I think the act of translation is, like we’ve discussed above, this infinite journey toward a meaning that you’ll never find. There is no way to translate a poem sufficiently, and the act of trying to to impart some small sliver of what called me to the poem is a pursuit that’s deeply frustrating and deeply rewarding, and I hope that some of the translations I complete have a similar spark for others. E

VKN: Your recent museum visits in Istanbul made me think of this: When I was in Houston, visiting the Rothko chapel, though not intended, I thought the chapel feels very Islamic, sacred and beautiful, and demands quietness and deep contemplation. Is there a place in the states that makes you feel like you have entered a mosque? In the chapel, I kept on looking over my shoulders hoping to hear the call for prayer. But footsteps and silence could behave like that. Your last poem makes me feel this way.

AW: I would say the Rothko Chapel as well. I grew up in Houston, and the Rothko Chapel remains an important place that I return to every time I’m home visiting my family. I think you’re absolutely right about the similarities of the feeling of the space, both the architecture of the interior as well as what Rothko’s paintings do as similarly evocative to the mosaics within the mosques. Some of the only times I’ve felt that otherworldly tug are the first time I entered the Blue Mosque and the times I’ve entered the Rothko Chapel.

VKN: You will return back to the states soon, yes? When will you visit Istanbul again? Are you still teaching there? Perhaps you do not desire the states to be your home for the fourth time, accidentally. What do you hope to desire with the current political conditions?

AW: Yes, I fly back to Los Angeles on Tuesday (two days from now). I’m hoping to be back in Turkey sometime in the spring, but I don’t have a firm plan yet at least. I would be happy to return to Koç and teach there again if I’m lucky enough to return to Istanbul. Zel and I do also love Los Angeles, which has been a home base for me since I first moved there in 2002 and where many of my best friends live. I’m lucky to have multiple places that give me a sense of home and that bring me happiness, even if my desire was to remain here in Istanbul. Right now, I’m trying not to desire anything in particular and just continuing to work toward tomorrow.

VKN: I am about to turn into a pumpkin. It’s midnight here and I will probably go to sleep soon. I walked twenty minutes to a grocery store to interview you. Every now and then, a woman on a speaker will tell me every fifteen minutes to have a great day when it’s night and dark here. I will walk back. And, what will you have for lunch, Andrew?

AW: Once we’re done, I’ll eat a Turkish breakfast–cheeses, olives, breads, tomato, cucumber, jams. I think it’s important for all our nights to also be great days, even if they are happening in the grocery store. Thank you so much for walking to that grocery store, Vi, and asking me these questions! This was an absolute delight.