The Final Days: Seeing Bush, Thinking Nixon

09.08.06

WASHINGTON, AUG.8—________________, the ___ President of the United States, announced tonight that he had given up his long and arduous fight to remain in office and would resign, effective noon tomorrow.

WASHINGTON, AUG.8—________________, the ___ President of the United States, announced tonight that he had given up his long and arduous fight to remain in office and would resign, effective noon tomorrow.

Although this lede from a top story in The New York Times ran exactly 32 years ago today, it is not entirely absurd to imagine the so-called newspaper of record publishing the same paragraph this morning just by filling the redacted blanks “Richard Milhouse Nixon” and “37th” with “George Walker Bush” and “43rd.”

A recapitulation of Bush’s “long and arduous fight to remain in office” presumably would follow. The highlights might include: his twice electorally dubious path to the White House; his flouting of both Constitutional and international laws; his dismissal, as invalid, of a memorandum entitled “Bin Laden Determined to Attack Inside the United States,” which he received in his August 6, 2001 daily briefing, while enjoying a month-long “working” vacation; his administration’s conscious neglect, again while the president was on vacation, to prepare adequately, or even at all, for one of the worst natural disasters in the country’s history.

Somewhere within this hypothetical news story or in a “news analysis” accompanying it, it would be noted that the president’s resignation had become inevitable this past March when his job approval rating, according to a CBS News poll, tanked to a breathtaking low of 29 percent. (The vice president, whom the nation understood was more accurately a co-president and quite possibly the de facto president rated a mere 18 percent, having recently shot a man in the face). Bush’s approval rating has recovered mildly since, but, as even cautious polls indicated, as of last week it remained stalled at around 40 percent.

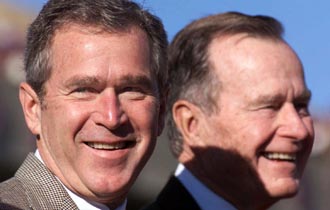

The resulting opinion pieces would have easy pickings. The outgoing president, a former co-owner of the Texas Rangers, had tended throughout his political career to understand problems of all variety and scale in the fraternity-brother cum MBA’s lingua franca of professional sports (e.g. his comment during the 2000 campaign that Times reporter Adam Clymer was “a major league asshole”). No hack political commentator inclined to baseball metaphors (and not named George Will) could resist the opportunity to snicker upon Bush’s resignation that .400 is a Hall of Fame average for an MLB batter, but that 40 percent as an approval rating for a wartime commander in chief was something short of inspiring. Arguably, a man in his situation ought to have maintained at least a majority show of confidence if he wanted, as this president had repeatedly put it, to “stay the course”; the same locution his father, “41,” had adopted whenever his own numbers had looked wobbly. In the end, a clear majority of the nation had become convinced that the course to stay—namely the military occupation of Iraq—should never have been plotted in the first place, and it was this development, all the members of the Washington press corps would agree, that had finally brought down the Bush II reign.

Obviously, a version of this news story ran thirty-two years ago, but it will not run today. That’s a difference worth lingering over this morning. If history’s malfeasants were interchangeable, then history would have repeated itself and a 44th POTUS would be taking an oath of office this afternoon. Instead, a pattern has been disrupted.

Until this week the parallels between the years 1968-1974 and 2000-2006 had been more or less consistent—two halves of a macabre Rorschach image fairly simple to decipher. Even in places where the symmetry petered, mirror images usually emerged. Suppose for instance that Dick Cheney, the former CEO of charmed government contractor Halliburton, whose stock prices tripled in the first two years after the invasion of Iraq, had been pressured to resign for graft, just as Vice President Spiro T. Agnew had been under Nixon. Wouldn’t House Speaker Denny Hastert have played the custodial role of Gerald Ford obligingly?

Until this week the parallels between the years 1968-1974 and 2000-2006 had been more or less consistent—two halves of a macabre Rorschach image fairly simple to decipher. Even in places where the symmetry petered, mirror images usually emerged. Suppose for instance that Dick Cheney, the former CEO of charmed government contractor Halliburton, whose stock prices tripled in the first two years after the invasion of Iraq, had been pressured to resign for graft, just as Vice President Spiro T. Agnew had been under Nixon. Wouldn’t House Speaker Denny Hastert have played the custodial role of Gerald Ford obligingly?

When Cheney returned to Washington in January 2001, his was not an unfamiliar face. He’d gotten his start in the Nixon administration, where he was an assistant to the director of the Office of Economic Opportunity, Donald Rumsfeld, who was also coming back to reclaim a Cabinet appointment he held under Ford. Cheney and Rumsfeld arrived with another former colleague from those days: the neocon hawk Paul Wolfowitz, who served, oddly enough, in Nixon’s Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. Even a new figure, Karl Rove, the strategist Bush brought with him from Arlington, had been here before. Rove, whom the President called his “turd blossom” and whom the Washington press corps referred to with sobriquets—architect, boy wonder, genius—once reserved for the cult of Henry Kissinger, had learned his trade as a mole for senior-CREEP “ratfucker,” Donald Segretti.

But John N. Mitchell was dead. John Dean and Henry Kissinger were understandably content in Manhattan where their bylines and consulting acumen remained in high demand. G. Gordon Liddy would have been a long shot to get past Congress. And the new President’s father, whom Nixon had handpicked for the Republican Party chairmanship (1972-74) mainly because he viewed him as an unwitting cipher, had other plans. Old friends like Cheney, Poppy’s former secretary of defense, could baby-sit the prodigal son for a while. The Bush family coffers, which had always relied on the unique reciprocity between petroleum and destabilized Third World countries, were better served in George pere’s advisory capacity to the Carlyle Group, an international private equity firm whose investors included members of Osama Bin Laden’s family. Anyway, as numerous magazine profiles reminded us there was habitually tension between 41 and 43. “There’s a higher Father that I appeal to,” George W. Bush said.

These veterans and others would be absent from the reunion at Pennsylvania Avenue, but nonetheless it was plainly Nixon alumni who dominated the White House’s new inner circle. To this team of military-industrial complex all-stars, the president added a pair of manipulatable loyalists from Reagan-Bush I era: Condoleezza Rice and Colin Powell. It was a crack squad designed to swallow whole the interregnum between 1974 and 2000—to supplant history.

“There is no reasonable parallel of any sort between Iraq and Vietnam.” This was from Christopher Hitchens last year in a reluctant nod to a talking point that, since the March 2003 invasion by U.S. forces and its motley “coalition of the willing,” has been invoked commonly among those who would have us stay the course.

“There is no reasonable parallel of any sort between Iraq and Vietnam.” This was from Christopher Hitchens last year in a reluctant nod to a talking point that, since the March 2003 invasion by U.S. forces and its motley “coalition of the willing,” has been invoked commonly among those who would have us stay the course.

Headlines such as “Iraq Is not Vietnam” and “Iraq Is No Vietnam” and other more creative variations of this theme (i.e. in the March/April Foreign Affairs, “Seeing Baghdad, Thinking Saigon”) have been fixtures not just of D.C.’s most specialized wonk journals but also among the reliable clichés of the popular media. The notion that the quagmire in Iraq had nothing in common with the one in Vietnam quickly evolved into more than a stated position. It accumulated the aura of a mantra—a happy phrase spoken to fulfill the promise of its own desperate hopes. And as the occupation floundered, the use of this mantra became ever more necessary, a type of mass autosuggestion.

That the constant pronouncement of such slogans appeared to encourage the very skepticism they were intended to dampen is an irony lost on those busily intoning them. For all the effectiveness they have had on the polls, which show that the majority of Americans do not any longer have faith in the war’s mission, one might as well have shut one’s eyes and repeated, “George W. Bush is not Richard M. Nixon.”

Recently a commentator in Policy Review conceded that the Iraq and Vietnam wars do indeed have something in common—“in both cases American forces have fought revolutionaries”—but that this resemblance was not especially meaningful so long as the United States held its resolve. Had the Oval Office issued a new talking point? Or rather, had it issued an old one? Last week, Gen. Peter Pace, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, testifying before the Senate Armed Services Committee, acknowledged the possibility of civil war erupting in Iraq. The general then reminded his inquisitors that, “Our enemy knows they cannot defeat us in battle. They do believe, however, that they can wear down our will as a nation.”

The old saws from Vietnam, they have returned to Washington, too. Some of the idioms naturally have morphed over time. Where there was once a “domino effect” in Southeast Asia that we had to stop, there was now, according to one National Review author, a “demonstration effect” of democracy we needed to implement across the Middle East. Three decades have passed. The Oval Office has changed hands six times. But the logic we apply is apparently timeless.

When President Nixon, in a televised speech to the nation on November 3, 1969, called on a “silent majority” to get behind an increasingly unpopular bloodbath, his intent was not to unify a divided country so much as to rattle his saber at the vocal minority.

When President Nixon, in a televised speech to the nation on November 3, 1969, called on a “silent majority” to get behind an increasingly unpopular bloodbath, his intent was not to unify a divided country so much as to rattle his saber at the vocal minority.

Let us be united for peace. Let us also be united against defeat. Because let us understand: North Vietnam cannot defeat or humiliate the United States. Only Americans can do that. (Emphasis mine)

The president “had identified a foe within the United States more dangerous to the country than the one it was fighting in Vietnam,” Jonathan Schell wrote in The Time of Illusion, an account of the political symbiosis between the fighting in Southeast Asia and the dirty tricks that led to the Watergate scandal at home. “Thereafter,” Schell continued, “the Vietnam War would be waged primarily in the United States.”

It is this ideological conflation of the foreign and domestic theaters that has been the most profitably mimicked tactic of the Nixon administration over the last six years. As a candidate in 2000, Texas Governor George W. Bush declared his interest in improving the “tone” in Washington. He called himself a Washington “outsider” and, though he never dared say it explicitly, the coveted independent voter demographic was meant to believe that the “tone” Bush was referring to was the bilious aura of the capitol before, during, and after the Clinton impeachment—never mind that the tone was stoked by his own Republican party. Yet, when the president announced on November 6, 2001, that, “You’re either with us or against us in the fight against terror,” his admonishment was clearly directed not solely at foreign states hesitant to join the coalition of the willing, but more pointedly at dissenters within America’s own ranks.

“September the 11th changed the strategic thinking, at least, as far as I was concerned, for how to protect our country,” Bush explained impatiently at a press conference two weeks before U.S. forces began their siege on Baghdad. “September the 11th should say to the American people that we’re now a battlefield.”

Among those who did not fail to intuit the essential meaning of Bush’s language was New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg. Although fewer than one in five of his constituents had pulled the lever for George W. Bush in 2000, and although the promised increase in federal security funding for the city had not been forthcoming, Bloomberg allowed the 2004 Republican National Convention to meet in Midtown, even as he denied protestors a permit to assemble and demonstrate in nearby Central Park. Asked what he thought about the vehemence of the estimated half-million people who instead marched past Madison Square Garden the day before the convention, Bloomberg said,

Think about what that says. This is America, New York, cradle of liberty, the city for free speech if there ever was one and some people think that we shouldn’t allow people to express themselves. That’s exactly what the terrorists did, if you think about it, on 9/11. Now this is not the same kind of terrorism but there’s no question that these anarchists are afraid to let people speak out.

Another person who clearly understood the president’s use of “us” and “them” was Bill Clinton, who identified the gambit in his address that summer to the Democratic National Convention in Boston.

Since most Americans aren’t that far to the right, our friends have to portray us Democrats as simply unacceptable, lacking in strength and values; in other words, they need a divided America.

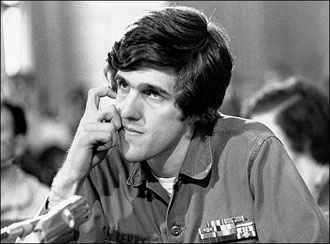

Someone who did not appear to understand the nuances of the President’s cunning was Senator John Kerry. As he would throughout his campaign, one in which he accepted the Democratic nomination by “reporting for duty,” Kerry engaged his adversaries on their own militarized terms. If post-September 11 America was a “battlefield” as Bush insisted, then Kerry’s dutiful salute seemed a reassuring signal to conservative voters, a way of saying that he was not one of “them”—meaning those who opposed the war—but one of “us.”

Someone who did not appear to understand the nuances of the President’s cunning was Senator John Kerry. As he would throughout his campaign, one in which he accepted the Democratic nomination by “reporting for duty,” Kerry engaged his adversaries on their own militarized terms. If post-September 11 America was a “battlefield” as Bush insisted, then Kerry’s dutiful salute seemed a reassuring signal to conservative voters, a way of saying that he was not one of “them”—meaning those who opposed the war—but one of “us.”

As a Vietnam veteran running against a ticket of two draft evaders, Kerry’s tough guy credentials were supposedly airtight, unassailable. His service record was the heart of his appeal for the Democratic Party establishment, which had unofficially chosen him as their man as far back as the time when Howard Dean was still the frontrunner (when Dean was still referring to Congressional incumbents, including those in the Democratic party, who had appeased Bush in his first term as a “bunch of cockroaches.”). But after completing his tour of duty, Kerry also famously testified before Congress against the Vietnam War, and it should have been obvious to Democrats who welcomed Dean’s implosion that, in the minds of conservative voters, Kerry—fairly or not—was always going to be one of “them.”

Not that Kerry hadn’t made a concerted and sustained push to ingratiate himself with the stay-the-course voter. As a senator, Kerry had voted, along with most of his Democratic colleagues, to grant the President the authority to invade Iraq. It was a position, his supporters argued, that he had to take in order to later deflect the expected charges that he was soft on security issues. Any challenge to the president, went the argument, while his approval ratings soared and Republicans had control of the Senate, would have made no difference. But in his general election campaign, Kerry criticized the president’s handling of the war from every conceivable angle, accusing Bush of “colossal misjudgments” and of “misleading” the public, but never, as Dean had, of “lying.”

And when moderator Jim Lehrer asked the senator in the first of his three debates with Bush, “Are American’s now dying in Iraq for a mistake?”—a reformulation of a question Kerry asked Congress in 1971 (“How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?”)—he offered a hollow campaign boast: “No, and they don’t have to, providing we have the leadership that we put—that I’m offering.”

Even before the invaluable paucity of John Kerry, a George McGovern to Howard Dean’s Ed Muskie, George W. Bush already possessed a bountiful repository of able straw men in the majority of Americans, not at all silent, who had voted against him in 2000. And in Osama Bin Laden, conveniently at large, Bush had an enemy he could expect us all at a moment’s notice to rally against. Fluffing up the “evildoer” Saddam Hussein had nothing to do with inventing another bogeyman, just as the ostensible War on Terrorism and all the neocon frothings about democracy spreading across the Middle East—parsed with grave attention in newspaper editorials—were at best tangentially relevant to the true aims of the second Gulf War.

Even before the invaluable paucity of John Kerry, a George McGovern to Howard Dean’s Ed Muskie, George W. Bush already possessed a bountiful repository of able straw men in the majority of Americans, not at all silent, who had voted against him in 2000. And in Osama Bin Laden, conveniently at large, Bush had an enemy he could expect us all at a moment’s notice to rally against. Fluffing up the “evildoer” Saddam Hussein had nothing to do with inventing another bogeyman, just as the ostensible War on Terrorism and all the neocon frothings about democracy spreading across the Middle East—parsed with grave attention in newspaper editorials—were at best tangentially relevant to the true aims of the second Gulf War.

Asked at a press conference to comment on the rash of international anti-war demonstrations in the weeks preceding the invasion, the president said,

I’ve seen all kinds of protests since I’ve been the president. I remember the protests against trade. A lot of people didn’t feel like free trade was good for the world . . . That didn’t change my opinion about trade.

So closely were the interests of war and business aligned in the president’s thinking, that it did not occur to him, or to his interlocutor, that there was any impropriety in his analogy. Of course, the president was not revealing anything that the available evidence did not already show. For one to locate the motivation behind the U.S. occupation of a formerly sovereign country that played no role in the September 11 attacks, tone needn’t look any further than the petroleum industry’s annual reports, or for that matter, June’s headlines in The New York Times (June 12, “Bush Sees Oil as Key to Restoring Stability in Iraq”; and June 19, “Company Ties Not Always Noted in Security Push”).

Bush “professes a compassionate conservativism,” Joe Conason wrote in a 2000 Harper’s article detailing Bush’s connections to both the Texas and Middle East energy trade. “But his true ideology, the record suggests, is crony capitalism.”

On February 6, 2003, every newspaper in America published on their front pages a set of pixilated, barely legible satellite photographs from the presentation Colin Powell had made to the United Nations Security Council the morning before. The photographs, Powell said, were evidence (or “PROOF” as the New York Post headline put it) that Saddam Hussein was manufacturing chemical and biological agents—the weapons of mass destruction, or WMDs. In a “before” image what looks like a truck and a tent were, with the aide of the captions that the newspapers helpfully provided, discernible. In an “after” image, purportedly taken on the day of a U.N. inspection, the truck and the tent were gone. These were pictures that perhaps could rise in a charitable United States courtroom to the level of circumstantial evidence, but it was not clear how they could be said to be proof of anything. In fact, to the average office worker, this slideshow should have had all the credibility of the vacuous PowerPoint charts without which their inarticulate managers would during meetings find themselves helpless. Powell’s farcical attempts to convince the international community of an imminent threat to America—a threat of which we learned later he had not himself been convinced—were a vivid emblem of what had been called America’s first MBA presidency. Revenue, not policy, was this administration’s forte, and when required to explain itself it found recourse in the same methods—obfuscation, deferral—that perennially keep shareholders and the I.R.S. at bay.

On February 6, 2003, every newspaper in America published on their front pages a set of pixilated, barely legible satellite photographs from the presentation Colin Powell had made to the United Nations Security Council the morning before. The photographs, Powell said, were evidence (or “PROOF” as the New York Post headline put it) that Saddam Hussein was manufacturing chemical and biological agents—the weapons of mass destruction, or WMDs. In a “before” image what looks like a truck and a tent were, with the aide of the captions that the newspapers helpfully provided, discernible. In an “after” image, purportedly taken on the day of a U.N. inspection, the truck and the tent were gone. These were pictures that perhaps could rise in a charitable United States courtroom to the level of circumstantial evidence, but it was not clear how they could be said to be proof of anything. In fact, to the average office worker, this slideshow should have had all the credibility of the vacuous PowerPoint charts without which their inarticulate managers would during meetings find themselves helpless. Powell’s farcical attempts to convince the international community of an imminent threat to America—a threat of which we learned later he had not himself been convinced—were a vivid emblem of what had been called America’s first MBA presidency. Revenue, not policy, was this administration’s forte, and when required to explain itself it found recourse in the same methods—obfuscation, deferral—that perennially keep shareholders and the I.R.S. at bay.

One year later, when those WMDs had not been found and after it had been demonstrated that the intel Powell relied on for his statements had been doctored, FOX News reporter Brit Hume asked Dick Cheney, “Does your gut tell you that someday they will be found or—either in Iraq or somewhere else?”

“I just don’t know, Brit. It’s such a big place,” said the vice president, taking Hume’s cue and shifting the discussion away from Iraq to somewhere, anywhere, else.

We’ve just found in Libya, where we’ve been invited in, because of the President’s leadership and the way we used force in Iraq, I think—we just were taken to a turkey farm by the Libyans where we were shown a very large quantity of chemical weapons….

Watergate, remember, was not the story of a single burglary in the Washington hotel that gave the scandal its name. The burglary was only a clue to the more systemic crime of rigging America’s elections. That Ohio, not Florida, would become the site for the latest Oval Office effort in 2004 to subvert democracy was quite predictable, and not just because the Ohio secretary of state was, as Katherine Harris had been in Florida, the state chair of the Bush-Cheney campaign. The signs were already there in an August 2003 fundraising letter in which Walden O’Dell, the CEO of Diebold Inc., the company that builds the voting machines for 37 states, including those used in Florida and Ohio, declared himself “committed to helping Ohio deliver its electoral votes to the president next year.”

Watergate, remember, was not the story of a single burglary in the Washington hotel that gave the scandal its name. The burglary was only a clue to the more systemic crime of rigging America’s elections. That Ohio, not Florida, would become the site for the latest Oval Office effort in 2004 to subvert democracy was quite predictable, and not just because the Ohio secretary of state was, as Katherine Harris had been in Florida, the state chair of the Bush-Cheney campaign. The signs were already there in an August 2003 fundraising letter in which Walden O’Dell, the CEO of Diebold Inc., the company that builds the voting machines for 37 states, including those used in Florida and Ohio, declared himself “committed to helping Ohio deliver its electoral votes to the president next year.”

But to feel any nostalgia this morning for the Watergate era one would have to forget that in 1972 Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward were hungry young reporters who by their own admission lucked into their story. They were able to pursue that story precisely because their esteemed colleagues did not think that burglars carrying thousands of dollars in cash and state-of-the-art surveillance equipment would possibly have broken into the offices of the Democratic National Party for political purposes. The incredulous reporters were four months into their investigation before they entertained the possibility that Nixon himself was involved in the plot to sabotage his opponents. So unsuspecting were Bernstein and Woodward that Nixon and his aides were felons, that they expressed shock in All the President’s Men that fellow journalist Seymour Hersh (who more than thirty years later is still responsible for the best reporting on an imperial presidency) “did not hesitate to call Henry Kissinger a war criminal in public.”

Campaign slush funds were a pivotal tool in Nixon’s electoral subterfuges, and amendments were made in 1974 to the Federal Election Campaign Act that were designed to further curb the disproportionate influence of money on government by providing matching public funds to candidates who submitted to spending limits. Yet in 2004, both George W. Bush and John Kerry forswore matching funds in the primary season and ran exclusively on private lucre. Even the maverick Howard Dean, who that year was raising a considerable portion of his money from very small individual contributions, declined matching funds, which would have financially hamstrung his challenge to the Democratic party establishment. Meanwhile, in 1999, Bill Clinton and Congress allowed to lapse the 1978 statute providing for the appointment of independent special prosecutors to investigate executive misconduct. It was a statute that in theory might have brought Ronald Reagan and his administration to justice for illegal arms sales, money laundering, and treason (including George H. W. Bush whose fingerprints were everywhere), but which instead had given the nation Kenneth Starr. Thus, the two most important legal reforms enacted to prevent a repeat of Watergate crimes have been permanently neutralized. In any case, a spokesman for Nancy Pelosi, the House minority leader presumed to be the next speaker if the Democrats were to actually retake Congress in November (as this season’s most optimistic meme goes), assured the Washington Post in May that “impeachment is off the table; she is not interested in pursuing it.”

As of today, Senator Howard Baker’s 32-year-old question—“What did the President know and when did he know it?”—is no longer operative. In its place, one might ask, what did the nation know and when did we know it? What comes next for America democracy is an unknown—besides, that is, the final 895 days of George W. Bush’s presidency.