“God Bless You, Kim Jong”

07.08.06

A couple weeks ago, I made fun of George W. Bush for claiming after North Korea’s failed Taepo Dong-2 missile test, that the United States had a “reasonable chance” of shooting said missile down—mostly because it seemed pretty ludicrous to me to boast about our ability to intercept a long-range intercontinental ballistic missile days after we knew it had already failed two minutes after its launch. It was a statement that necessitated a few qualifiers for Bush—among them, “at least that’s what the military commander has told me”—because selling the argument for rekindling missile defense required his audience to buy into a hypothetical situation: that we could have shot down the missile had it come within proximity of United States borders.

A couple weeks ago, I made fun of George W. Bush for claiming after North Korea’s failed Taepo Dong-2 missile test, that the United States had a “reasonable chance” of shooting said missile down—mostly because it seemed pretty ludicrous to me to boast about our ability to intercept a long-range intercontinental ballistic missile days after we knew it had already failed two minutes after its launch. It was a statement that necessitated a few qualifiers for Bush—among them, “at least that’s what the military commander has told me”—because selling the argument for rekindling missile defense required his audience to buy into a hypothetical situation: that we could have shot down the missile had it come within proximity of United States borders.

Of course, this didn’t happen. The Taepo Dong-2 missile, which was designed to test what U.S. intelligence believes to be a 3-stage ICBM with a range of 3,000-3,700 miles, didn’t make it past its initial booster phase. Technically speaking, the Taepo Dong-2 could reach Hawaii and Alaska. But more important was the symbolic nature of the test—not just for its July 4th launch, but for the psychological boost it gave to both the Great Leader in tormenting his arch nemesis, and to missile defense proponents in the United States. As Lt. General Robert Gard and John D. Isaacs wrote on the Web site for the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation: “These events represent a symmetrical international Kabuki dance: the North Koreans tested a missile with no idea whether or not it would function as intended, and the United States activated a missile defense system without evidence that it has the capability to intercept the North Korean missile.” And even more revealing of the symbiotic nature between NMD proponents and countries like North Korea is a quote from Donald Rumsfeld after the launch of the original Taepo Dong missile in 1998, “God bless you, Kim Jong.”

Kim Jong Il’s behavioral patterns aren’t unpredictable. The megalomaniacal dictator’s strident cries for attention are usually metered out when the world’s news focus is elsewhere. And it works, with a huge impact. If Kim Jong Il was half as good at feeding his country, the Taepo Dong-2 might have flown another five minutes (a joke seized upon by political cartoonists). The failure of the launch actually means very little for North Korea because Kim has the United States eating out of his hand, so to speak (a bad, unintended pun, I know). This isn’t to say I think North Korea has no intentions of improving its ICMBs, but more than anything, Kim sells fear; he remains obstinate in global politics and knows the U.S. is too mired in its own shitstorms in Iraq and Afghanistan (does anyone remember we’re still looking for Osama bin Laden there?) to make any military move against it, and he plays directly to the music of U.S. intelligence and defensive policy: the it could happen criteria.

This all seems pretty familiar. Just weeks before the first Taepo Dong launch, the Rumsfeld Commission released its July 1998 report that refuted findings in a National Intelligence Estimate three years earlier that said threats of missile attacks from a rogue nation like North Korea were at least 15 years off. The Rumsfeld Commission’s report was significant not only in defining a “discernable” (i.e. post-Soviet) threat by missile attack, but also, somewhat indirectly, in redefining in their own terms the standards on which national intelligence was, and would be, based. Previously the intelligence community focused on threats they considered likely events; after the Taepo Dong launch, they were forced to accept the Rumsfeld Commission’s much broader standard of what plausibly could happen. Oh, those crafty Republicans.

This all seems pretty familiar. Just weeks before the first Taepo Dong launch, the Rumsfeld Commission released its July 1998 report that refuted findings in a National Intelligence Estimate three years earlier that said threats of missile attacks from a rogue nation like North Korea were at least 15 years off. The Rumsfeld Commission’s report was significant not only in defining a “discernable” (i.e. post-Soviet) threat by missile attack, but also, somewhat indirectly, in redefining in their own terms the standards on which national intelligence was, and would be, based. Previously the intelligence community focused on threats they considered likely events; after the Taepo Dong launch, they were forced to accept the Rumsfeld Commission’s much broader standard of what plausibly could happen. Oh, those crafty Republicans.

With such wide-open criteria, the Rumsfeld Commission’s report, combined with the Taepo Dong launch, set the stage for NMD advocates like Paul Wolfowitz, Trent Lott, Newt Gingrich, and Rumsfeld himself, to push an extremely expensive project that has produced very limited results at best in its 50 years in development—and the Taepo Dong-2 launch appears capable of doing the same. Politicians leaped upon the Commission’s findings as proof of a concrete threat that necessitated billions of dollars of investment—threats not only based on the aforementioned looser standard of chance, but findings Dr. Richard Garwin, the Commission’s own (and only) physicist described to Frontline as thus: “We did the best we could with our limited charter. We said, ‘Yes, indeed there are countries that could, within five years, if they had a well-funded program and external support from missile powers and high priority on their program, they could have an ICBM which would be unreliable, inaccurate, and very few.’”

From 1985 to 2004, the United States has spent nearly $65 billion in developing a national missile defense. From 2004 to 2009, the projected budget is expected to require another $58 billion. The NMD budget item for 2007 is set at $10.4 billion. Since taking office, Bush has consistently requested nearly $10 billion in budget allocations toward NMD projects—all the while taking fire for pushing a political, rather than a technology-based schedule. Past incarnations of national missile defense in the United States have been the Nike-Zeus project in the 1950s, Project Defender in the 1960s, Robert McNamara’s Sentinel Program in 1967, and a scaled-down version, also in the late-1960s, called the Safeguard Program. All of the programs were highly theoretical and faced daunting and numerous obstacles of a technological nature. They also created a moral quandary (the idea of intercepting and exploding a nuclear-tipped ICBM in a friendly country’s atmosphere was not highly desirable). There was also the problem of jeopardizing the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction, a deterrent-theory based around the idea that if a country like Soviet Russia attacked the United States, the retaliatory nuclear strike would devastate their cities as bad as ours. But if a country could defend itself from nuclear attacks, nuclear saber rattling could quickly escalate to arbitrary extinction of rival nations.

NMDs at this time came in a variety of solutions, from intercepting ICBMs with nuclear missiles of our own, to orbiting satellites that would fire missiles that could deploy large mesh nets stopping the attack in the boost phase of the launch and presumably send it plummeting back to earth to meet its maker (most likely Soviet Russia). Further research showed intercepting missiles of a kinetic (non-explosive, akin to a bullet) type to be more useful, and indeed the U.S. has successfully tested hit-to-kill, defensive rockets like these in recent years.

NMDs at this time came in a variety of solutions, from intercepting ICBMs with nuclear missiles of our own, to orbiting satellites that would fire missiles that could deploy large mesh nets stopping the attack in the boost phase of the launch and presumably send it plummeting back to earth to meet its maker (most likely Soviet Russia). Further research showed intercepting missiles of a kinetic (non-explosive, akin to a bullet) type to be more useful, and indeed the U.S. has successfully tested hit-to-kill, defensive rockets like these in recent years.

The 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and its revision in 1974 allowed the two major Cold War players to each deploy a single ABM system within its own borders. The Soviets built its A-35 system around Moscow, and it’s still functional today under an improved A-135 system. In a decision that really doesn’t seem that weird anymore, the United States chose to protect its missile cache at the Grand Forks Air Force Base in North Dakota with Project Safeguard. Like the Soviet system, Safeguard utilized nuclear-tipped missiles to intercept enemy warheads. The Stanley R. Mickelson Safeguard Complex was built in 1975 and reached initial operating capability in April of the same year. On October 1, 1975 the site reached maximum capability, housing 100 interceptors, the maximum allowed under the ABM treaty. Safeguard, however, was mostly an illusion of defense—the Pentagon warned that the Soviets easily had enough nuclear ammunition to overwhelm the defenses, and in a secret memo to President Nixon, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger said Safeguard’s main contractor had no faith in the system. One day after reaching full capability, Congress voted to shut it down. Safeguard was the culmination of 20 years of research and development, and it lasted less than eight months and cost $25 billion.

In 1983, President Ronald Reagan introduced the Strategic Defense Initiative, which quickly became better known and derided as “Star Wars.” The Star Wars system aimed to shoot down nuclear missiles via nuclear-powered X-rays fired from space-based battle satellites, coupled with new control systems and ground-based defenses. Unlike previous theories of missile defense like Safeguard, which focused on limited-area defenses, SDI was to provide total coverage from full-scale nuclear attacks. Reagan’s program presented a twist on the Mutually Assured Destruction theory and instead boldly suggested that once the SDI was complete and perfected, would be shared with our Cold War nemesis. SDI would cost more than $44 billion over its 10 years of development, and obviously never fully advanced past this stage towards its very ambitious goals.

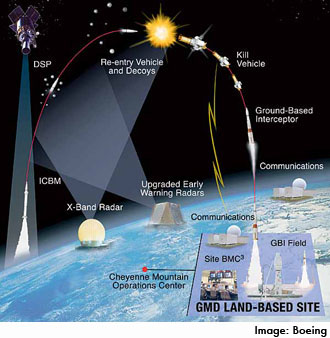

National missile defense is currently known in the United States as the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense, or GMD. The designation was updated in December 2001 after Bush decided to remove the United States from “the constraints” of the ABM Treaty, much in the same unilateral vein that seems to be this administration’s trademark, i.e. the Kyoto Accord and certain details of the Geneva Convention. (Actually, Bush laid the groundwork for this move in May 2001, but September 11 pretty much sealed the deal.) Currently we have limited ground-based missile defenses deployed in Alaska, and several hit-to-kill tests have been successful against mock ICBMs, as recently as February 2005. We still haven’t given up on the Gipper’s vision of lasers blasting nuclear warheads out of the sky like a game of Asteroids. Air-based laser systems are still in development, with vehicles ranging from satellites to B-2 bombers. The reality of this technology, however, is still pretty limited to a contractor’s computer animation and an artist’s renditions. More realistically, the GMD will expand deployment areas to Europe and incorporate naval defenses and computer technology into one encompassing system.

National missile defense is currently known in the United States as the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense, or GMD. The designation was updated in December 2001 after Bush decided to remove the United States from “the constraints” of the ABM Treaty, much in the same unilateral vein that seems to be this administration’s trademark, i.e. the Kyoto Accord and certain details of the Geneva Convention. (Actually, Bush laid the groundwork for this move in May 2001, but September 11 pretty much sealed the deal.) Currently we have limited ground-based missile defenses deployed in Alaska, and several hit-to-kill tests have been successful against mock ICBMs, as recently as February 2005. We still haven’t given up on the Gipper’s vision of lasers blasting nuclear warheads out of the sky like a game of Asteroids. Air-based laser systems are still in development, with vehicles ranging from satellites to B-2 bombers. The reality of this technology, however, is still pretty limited to a contractor’s computer animation and an artist’s renditions. More realistically, the GMD will expand deployment areas to Europe and incorporate naval defenses and computer technology into one encompassing system.

September 11 ushered in a new kind of world for the United States. On the one hand, it made it very clear what some countries think of us, an image we arguably haven’t much improved on since, and on the other hand gave the Bush administration free reign to do as they pleased in the name of national defense. And they sold it brilliantly—Bush and NMD advocates have repeatedly used September 11 as an example of why we need a missile defense shield, despite the fact that even in 1995, the NIE report which the Rumsfeld Commission was charged with refuting, stated that the likelihood of unconventional terrorist-type actions clearly outweighed the threat of an outright nuclear attack. And yet we’re as obstinate as Kim Jong Il is bent on flouting the rules of international nuclear armament, sinking hundreds of billions of dollars on a technology that we don’t have or possess, striving for a system that for the last 50 years has produced lots of very ambitious ideas and a few working models at best. It’s a thin layer of comfort and safety, and while North Korea may very well be working on improving their Taepo Dong-2 ICBM, it’s years from production and the potential threat of selling to another rogue nation one of possibly eight nuclear warheads already known to be in their possession is, in fact, very real.

So we can watch Bush swagger like a bemused cowboy and sell us the necessity of missile defense, experimental technology with a long history of failure and a few dubious successes that we’re supposed to trust will save us from nuclear attack. The total for technological onanism comes to $100 million per test—building up national missile defense for its own sake and lining defense contractors’ pockets for their CGI videos, when everyone knows it’s much easier, and precedented, for people to fly a plane into a building or detonate a bomb—even a dirty bomb—on a crowded train than it is to build a nuclear-armed ICBM. We might not want the smoking gun to be in the shape of a mushroom cloud, but if we knew it was coming could we pretend to stop it?