God’s Gaultier

01.09.06

Kathy Acker’s ghost. She’s shopping in San Francisco. She stares into a window. A second-storey window. What she sees: garments floating, fluttering. Gaultier, Westwood, Comme des Garçons.

Kathy Acker’s ghost. She’s shopping in San Francisco. She stares into a window. A second-storey window. What she sees: garments floating, fluttering. Gaultier, Westwood, Comme des Garçons.

“This,” she says to herself, “is the greatest store I have ever seen.”

Kathy Acker’s ghost moves among garments.

“Everything,” she says, “is so me.”

“Everything,” she says, “fits like a dream.”

As it should. The clothes are hers. Were hers. Kathy Acker died in 1997. Novelist, essayist, librettist—she left behind a beautiful body of work. She was also a shopper. She left behind a lot of labels.

Too Young to Die, Too Fast to Live. A slogan slapped on a Jean-Paul Gaultier gown. The gown’s vintage. Gaultier showed it in the late 1980s. A Vivienne Westwood suit coat. Norma Kamali body suits. Betsey Johnson babydolls. Yohji Yamamoto.

“This isn’t a store,” she says. She’s right: It’s an art gallery.

This isn’t a store. It’s a séance.

How to summon the spirit of a shopaholic?

Display the clothing she loved. Kathy Acker’s ghost slips in and out of outfits. “Who did this?” she says. “Dodie?”

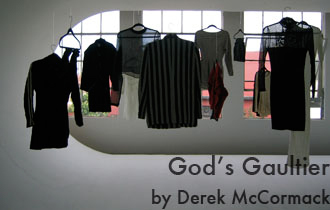

Dodie Bellamy, a brilliant poet and Acker’s contemporary. She installed Acker’s clothes at New Langton Arts Center in San Francisco this past summer. “Kathy Forest” she called the show.

“We hung the clothes from fishing line,” Bellamy tells me. “About twenty-five pieces, making sure there was enough space for people to walk between each piece. The clothes twirled in the breeze.” Shirts, skirts, shrugs. “Our idea was a forest of clothes, and after the fact, I named the exhibit.” If this was a forest, where were the trunks? Trees don’t twirl. Bodies do. Shades of a gallows. Shades of hangman’s trees. Corpse copse.

Shades of many things. A weird window display. A Halloween haunted house. A spiritualist’s salon where revenants roam. Bellamy was the medium. Q: What size dress did the spiritualist wear? A: Medium. Kathy Acker’s ghost wafts among her wardrobe. She lived in these clothes. These clothes lived through her. She was, without a doubt, the most spectacularly-clad writer I’ve ever seen. Who she was was wrapped up with what she wore.

I first came across Kathy Acker in an article in The Face in 1984. Acker, the magazine stated, “will wear wide, wide boiler suits over zipped and frilly nylon blouses, T-shirts exquisitely slashed, sinister silver jewellery of cockroaches and skeletons.” Accompanying the article, a portrait of Acker by Robert Mapplethorpe. She’s in a sack of a sweater. Her favourite designers, she said, were New York J.D.s (juvenile delinquents) who “don’t know much about the shape of the body yet.” “Street fashion is where the art is for poor people,” she said. “I can’t afford to buy a painting so if I get some money I go buy a dress.”

In 1988, I saw Acker read from Empire of the Senseless in Toronto. “[S]omewhat terrifying to behold,” is how The Toronto Star depicted her appearance. She was wearing Vivienne Westwood, from the Fall & Winter 1988 collection. The “Time Machine” collection, Westwood called it. A men’s coat. Grey pinstripes broken up by blocks of black. Sleeves were detachable. Sleeves were stitched together from what seemed to be pinstriped sports pads. Westwood said she’d been inspired by Roman armour. The coat’s references include gladiator garb, motorcycle jackets, roller derby-uniforms. Mad Max might have worn it to the office. When Acker moved, the pads parted, revealing her tight and tattooed muscles. On the bottom, she wore bondage pants.

In 1988, I saw Acker read from Empire of the Senseless in Toronto. “[S]omewhat terrifying to behold,” is how The Toronto Star depicted her appearance. She was wearing Vivienne Westwood, from the Fall & Winter 1988 collection. The “Time Machine” collection, Westwood called it. A men’s coat. Grey pinstripes broken up by blocks of black. Sleeves were detachable. Sleeves were stitched together from what seemed to be pinstriped sports pads. Westwood said she’d been inspired by Roman armour. The coat’s references include gladiator garb, motorcycle jackets, roller derby-uniforms. Mad Max might have worn it to the office. When Acker moved, the pads parted, revealing her tight and tattooed muscles. On the bottom, she wore bondage pants.

She signed my copy of Great Expectations, “Love, Kathy.”

I loved her books. I loved her clothes.

“Kathy had such élan, everything she touched was somehow made grander,” Bellamy writes in “Digging Through Kathy’s Stuff,” her essay on Acker, Acker’s clothes, and the creation of “Kathy Forest.”

Acker liked the outré, and designers who delivered it. Bellamy remembers her bedecked in a silver bodysuit “that looked like a prop from David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust tour, a tiny spacesuit.” Remembers “Kathy holding court in a femmy short plaid dress, empire style, tight around her bust then flaring out. Some kind of frou-frou at the shoulders.”

“Since no regular person would wear them,” Bellamy writes, “could one say these clothes ever were in fashion?” She interviewed Kaucyila Brooke, a photographer who documented over a hundred of Acker’s outfits. Among them: a white hoedown dress. An orange suit with a holstein-patterned collar. Stirrup pants, and not only one pair. Acker, says Brooke, had a bit of Liberace about her. I wonder: did Kathy Acker and Dolly Parton go shopping together?

“She looked like a clown,” Bellamy says in her essay, “but a totally confident, powerful clown.” Like Liberace, like Parton, like Prince—Acker created herself at least partly through clothing. “The gap between our intentions and the effects we create is what Diane Arbus ruthlessly brought into her photographs, a gap, that whenever I recognize it, opens a pang of love in me. Kathy managed to create exactly the effect she intended, but her clownishness, her bald construction of a persona also opened that gap.”

In the winter of 2006, Bellamy dug out Acker’s clothes. “On a shelf above our heads are stacked four large packing boxes,” she writes. “The bottom one is labeled in black marker ‘Acker’s Clothes’ in Kathy’s own handwriting. The boxes were packed by professional movers on the eve of her return from London in fall 1997.”

The clothes are kept in Los Angeles, in the care of Acker’s confidante and executor, Matias Viegener. “Once we get the boxes on the floor we start to rummage through them. Matias pulls out a black mass of fabric. ‘This one’s my favorite—I’ll never get rid of it—because nobody has been able to figure out how you’re supposed to wear it.’”

According to Viegener, Acker didn’t take terribly good care of her clothes. Food stains them…. Acker, he said, was a shopaholic. If she found something she liked, she’d take one in every colour. A black Gaultier dress grabbed Bellamy. It had a wool skirt with a diaphanous bodice. Sleeves of sheer mesh. A coat of arms embossed on the back. But whose family has such an insignia? In black flock, a consecration cross with 69 at its centre. Leaves sprout between the arms and neck of the cross. Lightning bolts blaze down either side. Scrolling over the cross, in faux-Gothic font: Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die.

According to Viegener, Acker didn’t take terribly good care of her clothes. Food stains them…. Acker, he said, was a shopaholic. If she found something she liked, she’d take one in every colour. A black Gaultier dress grabbed Bellamy. It had a wool skirt with a diaphanous bodice. Sleeves of sheer mesh. A coat of arms embossed on the back. But whose family has such an insignia? In black flock, a consecration cross with 69 at its centre. Leaves sprout between the arms and neck of the cross. Lightning bolts blaze down either side. Scrolling over the cross, in faux-Gothic font: Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die.

The dress is from Gaultier’s “Forbidden Gaultier” collection of 1987. I have a brooch from that show. It’s steel, a British bobby’s badge with the same slogan stamped into it. I couldn’t afford a dress. Gaultier winking at Westwood: Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die was, for a while, the name of the shop that Westwood and Malcolm McLaren ran on Kings Road in London. Later, it was known as World’s End. “Kathy often complained about not being famous enough,” Bellamy tells me. “Like she thought fame was her due and she’d been cheated out of it. So dressing in this famous designer, rock-and-roll, costume-y way was, perhaps, a way of shouting out that fame persona.

“Kathy’s Gaultier dress sits on my dresser, me on my bed writhing and grunting. It’s as if the dress has consciousness, is waiting for something, as I come I hear something coming from the dresser, something faint, a rustle, a breath.”

Bellamy took the dress home. Stared at it. Spoke to it. Had sex while it looked on. She wrote about it.

“Kathy’s dress sits atop my dresser and I want to turn this dress into a doll, it would resonate with voodoo, would resonate with Kathy’s stolen doll fucking passage, but the dress refuses to budge in that direction—the dress has presence, an aura, it sits there haughty as a popular girl who refuses to talk to me—stubbornly inanimate.”

A kind of alchemy.

This is what Bellamy did so beautifully with the Gaultier dress, and with the garments in “Kathy Forest.” She turned prêt-à-porter into ectoplasm.

“Ectoplasm, or teleplasm, as it is sometimes called, is a mysterious protoplasmic substance that streams out of the bodies of mediums,” wrote séance investigator Julien J. Proskauer in The Dead Do Not Talk. “This is manipulated by the spirits in order that they may materialize; hence, in a sense, they use it to shape themselves into a corporeal form.”

Acker wore her dresses, wore them out. Shaped them and stained them: blood, sweat, supper stains. Bellamy didn’t dry clean them. She hung them in an art gallery, where they seem spooky, spectral, signs from the afterlife. Like remainders from Acker’s life, but also like Acker’s doubles. Ectoplasm, according to occultists, is supposed to be the cloth from which the cosmos is cut—more substantial than matter itself. “Truly,” said British spiritualist Oliver Lodge in 1925, “it may be called the living garment of God.” What does it mean when God’s garment is a Gaultier? Is Gaultier God? Is Kathy Acker?

Is the universe stretch velvet?

On the second night of the “Kathy Forest” show, Bellamy delivered a reading of “Digging Through Kathy’s Stuff.”

On the second night of the “Kathy Forest” show, Bellamy delivered a reading of “Digging Through Kathy’s Stuff.”

“I wore an all white outfit,” Bellamy says, “because at the end of my talk I bring up an account of a reading Kathy gave of Eurydice in the Underworld a few months before she died, where she was wearing all white.

“Right before I went to read, I went to the bathroom, and this day-old cut on my thumb that had scabbed over, broke open and a few drops of blood fell onto the outside of the pants, down by the crotch,” she says. “The atmosphere of the reading was one of a ritualistic summoning of Kathy. So, of course it began with a spilling of blood.”

A little of her lecture: “As so often, Kathy’s outfit seems intrinsic to the experience. A slash of white in the darkness, she becomes an angel, Eurydice the death angel, her completely still body bleached in the darkness like a marble figure perched atop a tomb. When we transferred her ashes to the urn, ashy dust poofed into the air. All of us must have breathed it in.”

“Towards the end of my reading,” she tells me, “a huge cable fell from the ceiling of the auditorium and dropped right down into the audience in the form of a black noose. Everyone screamed and laughed. I had to wait quite a while for the audience to calm down to finish the reading. This convinced many that the clothes were haunted. After the reading, some people were too spooked to go up and look at the clothes again, but most people raced upstairs.”

“It was beautiful,” Bellamy says of reaction to her show, “a pervasive sense of connection and awe.” Some of the awe was amusing. “I was confronted with a lot of art-patron types,” she says. “Mostly women who wouldn’t stop talking to me, and who could spot a Vivienne Westwood or Comme des Garçons from across the room. I would get asked questions, ‘Where did she find a ‘Vivvy’ in San Francisco, I haven’t been able to find one here.’ It was all about shopping zeal and lusting after the clothes.”

In “Digging Through Kathy’s Stuff,” Bellamy quotes a line from A Discussion of Ghosts, a Buddhist book: “Happy ghosts live pleasant lives full of good food and beautiful clothes.”

The dead, like the living, crave nice clothes. Where does Kathy Acker’s ghost shop? Are there ghost boutiques? Ghost couturiers? Charles Frederick Wraith? Boolenciaga? Ghost? Do dead fashions have an afterlife?

Kathy Acker’s ghost is in Westwood. Something from the “Pirates” show. She is made of ectoplasm, as are her clothes. She is the same as her clothes—it’s an effect that she strove for in life, an effect that she’s finally sewn up.

As Acker once wrote: “It was the days of ghosts. Still is.”

And an Acker line I love: “I was in that store.”