My Life in the Bush of Words or, J.D. Salinger in Africa: Broken Glass, by Alain Mabanckou

25.05.10

Broken Glass

Alain Mabanckou

Soft Skull Press

176 pages

$13.95

Racism and colonialism may be our most public concerns and most jealously guarded political commodities, but the greatest difficulty facing black writers is actually a prohibition on self-loathing, a certain inability to hate oneself or “our people” with impunity. The impulse to extreme and sometimes satirical self-criticism tends to be shunned by many of us and attacked by many others in favor of outward gestures: the critique of power, oppression, and almost inevitably, racism. Sure, there are great misanthropes and bitter self-obsessed bastards in global black literary traditions. Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man comes immediately to mind, as does the work of George Schuyler, Jamaica Kincaid and the staggeringly under-rated Zimbabwean Dambudzo Marechera. There are others too but the tendency towards nobility and grace almost always wins out in our writing, as does the affirmation of oneself or one’s “people.” As a result the critique of external structures bends ever towards an assertion of black historical if not political innocence. The joys of disaffection and the creative possibilities of nihilism are left largely untapped due to a crippling obsession with pride and an almost totalitarian insistence on solidarity.

Now there are those who’ve been using the term “black nihilism” since the 1990s, by which they have meant that tendency in African-American popular culture since hip hop to eschew the glories of the outward gesture in favor of a seeming exultation in decadence and compromise. And in Africa, the term “Afro-pessimism” has emerged in the last ten years to describe literary and cultural responses to a social world where political independence has turned out to be far more dangerous than colonial oppression. To the radical imagination, these negative sensibilities are either a sign of political capitulation or of just how powerful those aforementioned structures remain in the wake of a generation that sharpened its teeth and its pens in the struggles against colonialism and racism. Neither of these are the self-loathing I mean, though Alain Mabanckou from the Democratic Republic of the Congo does make the kind of generational claims in his most recent novel Broken Glass that place him on the other side of that same historical divide; and capitulation, decadence and the joys of self-abasement are his themes. There is no innocence here: not in his work and not in his Africa.

Where hip hop’s nihilism and the literature that it has birthed tends towards grandiose performances of potency, what marks Mabanckou’s work is its interest in the internal gestures possible when cultural and political impotence are fruitfully acknowledged. He is a writer whose work is set in the central vortex of an Africa where both colonization and liberation have failed, and where cultural affirmation and political resistance have often turned to genocide. His world features the kind of violence that is enough to make any “hardcore” rapper blanch or become envious of material. In such a world, his is the kind of self-loathing that matters (and his most dubious distinction may be that he is the first to incorporate Rwandan genocide jokes into his fiction). Without this kind of brutal self-criticism and the will to render one’s own “people” complicit and less than noble, all outward critique rings false. Without this healthy skepticism of the self, it is impossible to mount any serious critique of society, history or their various structures without the easy and dangerous obfuscations of ideology or religious orthodoxy.

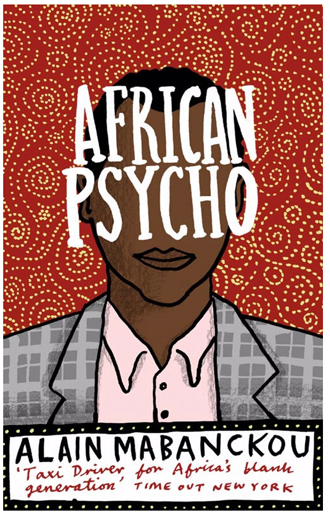

Broken Glass is Mabanckou’s second novel to be translated into English after the acclaimed and grandiloquent paean to impotence that was African Psycho. Where Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho was driven by the boom-economy privileges that could make murder a mere lifestyle accessory in the over-developed world, Mabanckou’s would-be killer couldn’t even act in a country where life was cheaper than beer and where the river that bisected the country was filled with more corpses than fish. Like other great novels about murder or crime as an act of liberation (from Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment to Richard Wright’s Native Son and Andre Gide’s Lafcadio’s Adventures, surely an influence on Mabanckou), African Psycho was largely about self-justification, excuses, interrupted and foiled opportunities. In short, it was about language; particularly a dialect from a country so far on the margins of metropolitan French, that it’s very right to exist was in some ways also a crime. French colonial policies were and are, after all, notorious for a rigorous policing of the language, one that had profound racial repercussions given that both immigration and assimilation were impossible without an accentless mastery.

Broken Glass is also the name of the novel’s narrator, busy writing the stories of the sodden yet voluble patrons of a bar called (what else) “Credit Gone West” at the behest of the barman, Stubborn Snail. He often reflects directly on the relationship between himself, his language and France. Now a disgraced ex-teacher, possible pedophile and devoted alcoholic he claims that “what mattered in the French language was not the rules, but the exceptions to the rules…the French language isn’t a long, quiet river, but rather a river to be diverted.” It is not difficult to hear Nabokov here; indeed it isn’t difficult to hear an army of others since Broken Glass is constructed by a dense web of literary in-jokes, allusions and references. On one page I was able to count as many as ten and that’s not including all those lost in the translation. Adding to his grotesque phantasmagoria, the entire novel is written in one, long—well, it can’t be called a sentence since it has no periods, starting capitals or other punctuation besides commas. In its own words “…it’s a real mess, this book, there are no full stops, only commas and more commas, sometimes speech marks when someone’s talking, that’s not right…”

Though quickly irritating despite being often poetic, its relentless enjambment first suggests the influence of Louis Ferdinand Céline whose work appears often in Broken Glass and whose name Mabanckou gives to a French woman “with a terrific ass on her, an arse like a real Negress from back home.” This Céline is described also as “the author” of one character’s decline, “his Dark Empire.” Secondly, this technique oddly recalls Nigerian novelist Amos Tutuola whose My Life in the Bush of Ghosts is here blended with Céline’s Journey to the End of Night and Death on the Installment Plan to quite remarkable cross-cultural effect. This doesn’t forgive the fact that by the end of this short novel, the narrative is in fact a mess. Even its willingness to admit it’s own limitations doesn’t quite redeem it in the same way that a clever apology doesn’t excuse a crime. It may be a fairly common gesture for sub-par writers of “meta-fiction,” but this kind of puerile self-reflexivity in no way stands in for insight into the admittedly exhausted techniques of narrative fiction.

As mentioned, the first two thirds of the novel feature a series of lurid and unbelievably depraved tales told by the regulars of Credit Gone West each attempting to make their way into Broken Glass’ “great book of life, of shit and tears.” Each tale goes deeper into the kind of self-abasement that can only be redeemed by an equally depraved listener, or a writer who has lost the right if not the capacity to judge. It would be easy to dwell on those stories, all of which seem calculated to shock and offend. They are in fact the weakest aspect of the novel. They are so pointlessly garish that they suggest that the writer has also lost the capacity to laugh.

Broken Glass is not really about the man raped so often in jail that he wears multiple diapers simultaneously; or the man who ‘did France,’ and whose opinion of other Africans would surprise the most devoted racist and who comes home to find his son in a masochistic sexual embrace with his French wife that is surprisingly predictable. The novel is also not the (though I must admit, quite brilliant) story of a literal pissing contest between a woman and a man in which the latter wins after sketching with his urine in the dirt a perfect map of France. Nor is it about the other tales that by the middle of the book lose narrative focus—not a good thing when your novel is a mere 176 pages.

Broken Glass is most obviously the story of that aforementioned diversion of French. It is when the barroom stories are exhausted that the novel abandons crude and random storytelling and focuses on its primary interest: literature and its possibilities for an African writer. Mabanckou is desperate to assert his commitment and connection to a broader world and sense of tradition than that determined by his country or his skin. In his now infamous manifesto “The Song of a Migrating Bird: For A World Literature in French,” he did emphasize such a commitment and connection by claiming that he felt much closer to Céline (the author, not the woman reduced to buttocks) than to Nigerian Nobel Laureate Wolé Soyinka. To him Soyinka was a “stranger” despite their race and a shared continent.

“The Song of a Migrating Bird” was a manifesto of what’s called la Francophonie, that increasingly self-conscious diaspora of French-speaking writers, dialects and creoles. But there is much more to Mabanckou’s diversion of French since Broken Glass is equally invested in so many other literary and cultural traditions. In a method that I can only describe as ecstatically scatological, the novel maps a commitment to multiple literatures: French, American, African-American, Latin American, English, and continental African. It claims also all that comes with them, from jazz to soukous, cartoons to pornography and politics to the very detritus of global popular culture, which ends up where all detritus does—in Africa, mountains of it suitable only for the recycling properties of language.

The final pages of Broken Glass do read like a manifesto, with all its talk of being or becoming a writer, of the various clichés and expectations of the African writer and its intense mockery of certain African writers and intellectuals. It is particularly hard on those who dream of the Nobel Prize only to dramatically and publicly reject it. In this spirit the novel reduces the “noble” or “radical” pretensions of racial struggle or black writing—all its talk of “the sobbing of the white man, phantom Africa, the innocence of the black child”––to a series of bad jokes (and his covert riffs on African-American literature are priceless and ballsy). So despite the brutality of the world represented here, it is difficult to reduce the black/African world to its deprivations and suffering. It is also difficult to maintain that salvific tendency that always sees in African suffering a “triumphant human spirit.” Mabanckou loathes these clichés and attempts to draw them out as bankrupt by pairing such grotesque material with the kind of irony we thought only existed in the disaffected West.

However, despite its dizzying globality and its omnivorous aesthetic, I must admit to seeing something particularly French in Broken Glass. Not just because of that tradition’s strong history of manifestos but because no other literary tradition is better at self-loathing. From Camus, Céline, Gide and Genet (again, all present in this book) to Michel Houllebecq—nothing comes close, or is quite as refined. I say this despite the rich tradition of Oxbridge writers such as Martin Amis and Will Self who like the French are fully aware of self-evisceration as a necessary gesture in class or cultural criticism. I say this also despite the fact that the American tradition would have to include J.D. Salinger, whose Holden Caulfield (or someone pretending to be since he actually carries a copy of The Catcher in the Rye) appears in the last pages of Broken Glass.

This character appears to Broken Glass calling him “a has-been, an old man” and repeating ad nauseum Salinger’s famous refrain from The Catcher in the Rye, the one about the ducks in Central Park and where do they go in winter. It is to this character that Broken Glass hands the narrative that is Broken Glass, declaring that he will answer that question for once and for all. “Holden” commands so many pages without explanation that one wonders if he exists simply to make a cross-cultural point about generational nihilism, self-loathing, extreme profanity and a general literary miserablism that all too often passes for authenticity. Whatever that point may ultimately be, that final gesture is a potent one. It leaves us with an inverted image of literary and cultural exchange that though it answers no questions, is absolutely rich with promises.

—————————————————————

Purchase a copy of Broken Glass here.

Related Articles from The Fanzine:

Louis Chude-Sokei on The New Era of Blackface and Fiction Across Borders