And Everything is Going Fine: Soderbergh on Spalding Gray

21.05.10

“I get tired of talking about myself,” says Spalding Gray midway through Steven Soderbergh’s new documentary about the late monologist, “so the conversations with the audience are a way of talking to other people . . . and hopefully empathizing with other people.” What follows is a moving yet deeply ironic clip of Gray interviewing a middle-aged woman as part of his well-known performance, Interviewing the Audience. Gray originated this piece in the early 1980s, when he was roughly forty years old.

“I get tired of talking about myself,” says Spalding Gray midway through Steven Soderbergh’s new documentary about the late monologist, “so the conversations with the audience are a way of talking to other people . . . and hopefully empathizing with other people.” What follows is a moving yet deeply ironic clip of Gray interviewing a middle-aged woman as part of his well-known performance, Interviewing the Audience. Gray originated this piece in the early 1980s, when he was roughly forty years old.

“Did you ever try to kill yourself?” Gray asks the woman seated onstage.

“No,” she replies without hesitation. “Life’s so short that it’s the least you can do to hang in.” Gray seems taken aback by her certainty. “You’ve really never thought about it?” he repeats. The woman explains that her ex-husband recently killed himself. His fatal act left her very angry, even though they had not spoken in over a year. “If you can’t make it any other way,” she states matter-of-factly, “you can do it that way.”

Soderbergh is a master of incongruous moments. While this segment begins with Gray’s expressed desire for connection to people outside of himself, he clearly cannot grasp his interlocutor’s aversion to suicide. His face grows troubled—even dumbstruck—when his female audience member dismisses killing oneself as an easy way out.

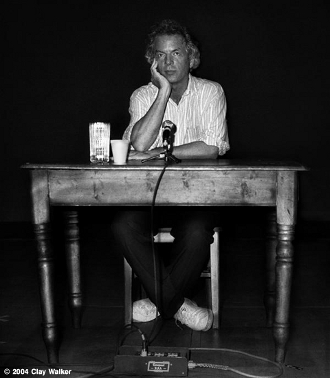

By contrast, Soderbergh and his crew embrace Gray’s lifelong fascination with self-induced death. On one level, the documentary functions as a visual chronology of Gray’s reflections on this topic. Soderbergh begins with a shot of Gray’s iconic wooden desk. Gray sits behind it, opens his notepad, and sips from a glass of water. Most fans will instantly recognize the ensuing material as Sex and Death to the Age 14 (1979), his first autobiographical monologue. I, for one, can almost recite Gray’s comic account of how his mother comforted his older brother Rocky when he could not fall asleep:

“Mom, when I die, will it be forever?”

“Yes dear.”

“Mom, when I die, will it be forever and ever?”

“Mm-hmm, dear.”

Soderbergh unsettles this familiar narrative about Gray’s childhood by intercutting more jarring footage of an older Gray discussing what it was like to grow up with a mentally ill mother. “Denial was the most difficult thing,” the performer tells an unidentified interviewer. To illustrate, Gray recalls playing in the house with other neighborhood children while his mother “shrieked in the kitchen, crying out. No one would say, ‘Was that your mother?’ We were all afraid.”

As followers of Soderbergh surely know by now, what makes this documentary unique (and a bit strange) is that Gray’s voice is the organizing principle. I saw And Everything is Going Fine at the IFC Center in New York on 6 April 2010. During a Q/A session after the screening, Soderbergh said he began with “90 hours of unique material” documenting Gray’s life and career. Unlike many traditional efforts to document reality, however, this project includes no expert opinions or posthumous interviews with people who knew Gray well. Instead, we get 89 minutes of Gray talking—mostly onstage or in film roles, but occasionally in the context of an interview with the media or a friend.

Some audience members questioned this mode of narrative by noting the absence of pivotal figures like the Wooster Group founder Elizabeth LeCompte, who helped to create the form of Gray’s monologues by instructing him to sit at a table and tell the audience about himself during the first part of Nayatt School (1978). I understand the call for a greater range of voices and perspectives. Nevertheless, I agree with Soderbergh’s sense that “there wasn’t a better way to tell the story than to have Gray tell it.” Conveyed any other way, this documentary would quickly succumb to the burdens of closure. And in the service of closure, Soderbergh would have little choice but to position Gray’s loved ones and colleagues as analysts who can somehow explain or justify his terminal act.

Gray is the only one who can resolve the mysteries of his disappearance, but he is no longer talking in the present tense. Nevertheless, Gray’s past is telling. Part of what draws me to Soderbergh’s assemblage of archival footage are his subtle insights into how much Gray lost as a result of his 2001 car accident. For example, the director includes a scene from A Personal History of the American Theatre (1980), a monologue in which Gray explains why his life changed when a drama teacher praised his timing. “Excellent timing—that’s everything, isn’t it?” a youngish Gray asks. Long after this segment ends, the fulfillment that Gray derived from timing remains on my mind. Indeed, finding “the perfect moment” became Gray’s obsession in his most famous monologue, Swimming to Cambodia (originally performed in 1984, and adapted in a film in 1987).

Yet by December 2003, Gray had lost his ability to select the precise instant for doing something. A few weeks before his death—after he closed his first run of an unfinished monologue titled Life Interrupted at P.S. 122—Gray recorded a final journal entry addressed to his wife, Kathie Russo:

Kathie, it’s an old story you’ve heard over and over. My life

is coming to an end. Everything’s in my head now, my

timing’s off, all this terrific hesitancy. In the last two years,

I’ve had ten therapists, maybe more. Not to mention three

psychopharmacologists and all those shock treatments.

Suicide is a viable alternative for me, instead of going to an

institution. I don’t want an audience. I don’t want anyone to

see me slip into the water.1

In maddening yet poignant ways, Soderbergh respects Gray’s dying wishes. In other words, And Everything is Going Fine makes a conscious decision not to reference Gray’s death. Even though much of the film intentionally charts the monologist’s thoughts on mortality, Soderbergh ultimately omits any footage of Life Interrupted (2003), and makes no overt mention of Gray’s suicide.

Instead, the film ends obliquely. Shortly after his devastating 2001 car accident in Ireland, Gray returns to America, where he is interviewed by a longtime friend, Barbara Kopple. “What are you worried about?” Kopple asks the artist, who now looks gaunt and pale, and walks with a visible limp. “The next accident,” Gray replies solemnly. Since their interview is set in the Hamptons, they talk about life on Long Island. Gray confides that he thinks he drinks too much in the Hamptons: “When I drink, I feel like I’m coming closer to my mother.” In the background of this sad conversation, a dog starts to howl. The dog sounds heartbroken, utterly forlorn. “The dog is already howling for the late Spalding Gray,” Gray says, chuckling softly. As the dog continues to howl, Gray laughs until his eyes fill. At the end of the clip, I realize he is on the verge of tears.

A weaker director might take Gray’s tears and run with them. After all, it would be easy to end this story with an image of water, since Gray’s fixation with lakes, rivers, and oceans played such an inexorable role in both his life and death. But Soderbergh resists the predictable. Instead, he concludes with a clip of Gray on dry land.

The documentary’s closing sequence is a home movie shot when Gray was an infant, barely able to stand. As a blond-haired baby boy plays with his dark-haired older brother in a suburban family yard, I realize we have come full circle. We are back at the beginning, but without really knowing the end.

1 Lunden, Jeff. “N.Y. Plays Channel Monologists Bogosian and Gray.” All Things Considered. 6 Mar. 2007. National Public Radio. 28 April 2010.

“Are there any secrets that I have?” Gray asks the camera at a much earlier point in Soderbergh’s documentary, “Are there stories I don’t tell?” Gray poses these questions while standing in front of a tombstone, perhaps his mother’s grave. “Yes,” he replies curtly and turns away. In such moments, And Everything is Going Fine hints at how little we knew of the man who made his life a public performance. “I’m afraid of life,” Gray tells an interviewer elsewhere in the footage, “because everything is chance. Doing the monologue is making it up: giving structure to what is normally chaos.” The artist’s admission that creating his life story involves fabrication (“making it up”) leads him to wonder if the process is “making him too extroverted, perhaps even pandering.” At the end of this clip, he laments the predicament that self-based performance has brought him: “No living; just writing.”

Gray did not finish writing his last monologue. Nor did he write a suicide note. Instead, he carried out some puzzling last acts. On January 9th, 2004, he was spotted riding the Staten Island Ferry, and was removed from that vessel for acting suspiciously. The following afternoon, January 10th 2004, Gray took his sons to a movie, Big Fish. That evening, he told his family he was going out for a drink with a friend. Hours later, Gray called his apartment from the ferry terminal. His son Theo answered, and Gray said he would be back soon. “Love you,” he reportedly said.2

Not unlike Gray, Soderbergh uses music to express what words cannot. Among the most emotionally searing scenes in the film is a clip from the end of Morning, Noon, and Night (1998). Here, Gray uses a bright yellow boom box to reconstruct a spontaneous family dance that he enacted at home one night with his wife and kids. Loud, ebullient music by the British band Chumbawamba fills the room. Gray looks positively goofy as he struts across the stage, first shimmying and pirouetting, then dancing like an Egyptian. Yet for once, he is clearly a man in love with people outside himself. The tears of grief that Chumbawamba’s “I Get Knocked Down” solicits are for a moment that did not last.

Powerful music again fills the theatre as Soderbergh’s end credits roll. This time, the music is a haunting rock requiem written by Forrest Gray, the teenaged son of Kathie Russo and Spalding Gray. Electrifying, tender, and raw: that is how I remember Forrest Gray’s tribute. A perfect match for the spirit of Soderbergh’s documentary, which is complexly affective: at once sad, moving, frustrating, and surprisingly funny. The film raises many questions. What is truly refreshing is that And Everything is Going Fine does not try to answer them. Instead, viewers are left remembering and filling in the blanks.

2 Wood, Gaby. “Profile: Shades of Gray.” Guardian Unlimited 26 Dec. 2004. Guardian.co.uk. 1 May 2010.

____________________________________________________________

Related Articles from The Fanzine:

Review of Soderbergh’s The Informant

Alex Segade on When Marina Abramovic Dies

Oscar B. De Alessi on Youth Culture, Representation and Suicide

Image on page two courtesy of artist Ali Hossaini. Learn more about his work here.

Also thanks to John Boland, who maintains the Spalding Gray website.