The New Era of Blackface

17.12.09

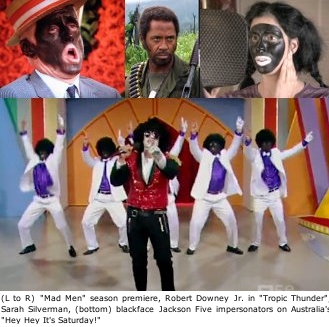

It should be clear by now that we are at the cusp of a new era of classic, no-holds-barred, in-your-face minstrelsy. Just this year alone blackface “incidents” have flared up in cultural zones ranging from America’s Next Top Model to critics’ darling Mad Men, from YouTube and Facebook to this years’ edgiest of Halloween costumes. French Vogue‘s recent photo-spread of a model in blackface was therefore less an act of racism than a calculated statement of the zeitgeist. That it so quickly followed on the heels of a now notorious blackface Jackson Five impersonation broadcast on Australian television was telling: the skit immediately went viral just as blackface did the moment it appeared in nineteenth century America.

It should be clear by now that we are at the cusp of a new era of classic, no-holds-barred, in-your-face minstrelsy. Just this year alone blackface “incidents” have flared up in cultural zones ranging from America’s Next Top Model to critics’ darling Mad Men, from YouTube and Facebook to this years’ edgiest of Halloween costumes. French Vogue‘s recent photo-spread of a model in blackface was therefore less an act of racism than a calculated statement of the zeitgeist. That it so quickly followed on the heels of a now notorious blackface Jackson Five impersonation broadcast on Australian television was telling: the skit immediately went viral just as blackface did the moment it appeared in nineteenth century America.

But what distinguishes this new era of classic blackface? It’s not so much those old habits of racism that commentators exult in pointing out but that blackface despite its known capacity to offend is now being used to confirm that the person underneath the mask and behind the stereotype is not racist. They are so convinced of this that they feel comfortable flaunting this taboo whether anyone is offended or not. Some of these resurgent examples of minstrelsy go so far as to suggest that blackface is the ultimate statement of anti-racism in that it emerges from a desire to criticize and mock racism itself. This certainly motivated the writers of Mad Men, America’s Next Top Model and tends to be a fallback position for too many drunken revelers. Call it “meta-anti-racism” if you dare call it anything at all. Like it or not this new confidence in “blacking up” does grow out of an aggressive refusal to be denied the pleasures and perils of racial parody, of taking things to the sharpest edge. And though it may be heresy to say, it is also a full-throttled attack on racial sanctimony and on the toxic notion that any one group has the last word on what is or isn’t offensive.

Perhaps the most aggressive sign of minstrelsy’s return to the media mainstream was the film Tropic Thunder. It was bold not only in its use of blackface, but in its daring to use it to not be about blacks at all. The film was probably most offensive to those for whom the very fact of blackface will always be about blacks and has always been categorically racist. This is not historically true, especially since blackface is fundamental to African-American popular culture even today. What the hostility to the film and its attempted mainstreaming of blackface suggests is something quite else: that the issue is not minstrelsy per se, but the white attempt to employ it. If this weren’t the issue then Tyler Perry would still be broke and most rappers would have stayed in school.

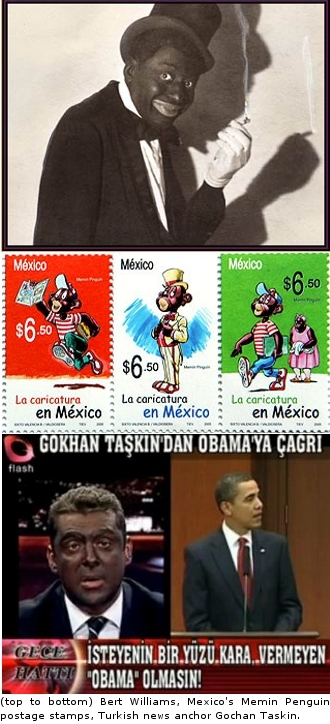

But what really marks this return of classic blackface is its globalization and emergence outside the control of American racial sensitivity: places such France, Australia, Turkey to name just a few; England, Mexico, Japan and the continent of Africa to name a few more. One example of American response to this phenomenon was in 2005 when Mexico was asked to withdraw a blackface postage stamp based on a beloved cartoon character Memin Penguin created in 1943. Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, then-President George W. Bush and an array of activist groups complained, leading Walmart to pull the comics from its shelves. The enthusiastic declaration of racism then prompted a defensive reaction among many Mexicans and Mexican immigrants that singled out the cultural insensitivity of Americans. Americans were being too quick to judge while knowing little of Mexico’s motives, racial histories or profound affection for the character. Arguably, it was that character’s beloved-ness that enabled a conversation about race in a country less willing, if not less equipped, than America to do so.

And just a few months ago a Turkish news anchor blackened his face in response to President Obama’s address to the Turkish Parliament. The American response to this was predictable though wrong-headed, since in Turkey blackening the face does not necessarily connote racial offense. In this case it was a half-comical sign of embarrassment, of shame, of having to prostrate oneself to American power in order to gain support for a number of Turkey’s most pressing national issues. So once again it was America’s judgment that was offensive. The accusation of “racism” was yet another example of bad foreign policy. Now the Australians may have shared the Turks’ befuddlement in America’s response, but in admitting they would never have performed the skit in the United States their “gee shucks” insincerity only bolstered the suggestion of actual racism.

For these countries the controversy ultimately had less to do with racism than with another old ism at the core of this new age of blackface: cultural imperialism. Lest we forget, for much of the world America is now officially a white country represented by a black face. The return of blackface as parody or homage was clearly inevitable. A black president may not be the sign of a “post-racial” America but for many across the planet he may be the sign of an America where blacks are perceived to be empowered enough to take a joke. Whether this is true or not is what partly motivates many of these global turns to minstrelsy. As in classic blackface there was always the assumption that blacks were the most potent symbol of America even amidst psychopathic racial hostility. To understand this, one need only hum a few bars of Dixie. In today’s hyper-mediatized world, blackface will continue to empower those who know that America’s dirty secrets are fair game and that its own internal contradictions make for great entertainment.

But minstrelsy was global from the get-go hence its inevitable return home. It traveled the routes of America’s 20th century imperial sprawl. Historical traces of it can be found from Northern Europe to the Middle East. Britain only cancelled its beloved “Black and White Minstrel Show” in 1978, and South Africa still celebrates its “Cape Town Coon Carnival.” The impact of blackface is still felt in West Africa of all places. There “tranting” and the “Concert Party” are forms of blackface theatre that can be traced to when colonized Africans began to mimic what they thought were freer, cooler and more politically empowered African-Americans. They blacked up, sang songs about “Broadway” and “Dixieland” and over the decades evolved a distinct style of extremely popular theatre. Ignorant of its origins in slavery and racism –– or in some cases simply uninterested in them –– minstrelsy produced something of enduring value to their equally black selves.

But minstrelsy was global from the get-go hence its inevitable return home. It traveled the routes of America’s 20th century imperial sprawl. Historical traces of it can be found from Northern Europe to the Middle East. Britain only cancelled its beloved “Black and White Minstrel Show” in 1978, and South Africa still celebrates its “Cape Town Coon Carnival.” The impact of blackface is still felt in West Africa of all places. There “tranting” and the “Concert Party” are forms of blackface theatre that can be traced to when colonized Africans began to mimic what they thought were freer, cooler and more politically empowered African-Americans. They blacked up, sang songs about “Broadway” and “Dixieland” and over the decades evolved a distinct style of extremely popular theatre. Ignorant of its origins in slavery and racism –– or in some cases simply uninterested in them –– minstrelsy produced something of enduring value to their equally black selves.

So in this international sphere the contexts and intentions of blackface are too distinct to dismiss as simply “racism.” To do so is to flagrantly miss the point. Today’s blackface tests the very right to comment on race and racism however crudely. The claim on blackface is a claim also on the right to reflect back to America images of its historical legacy or to use similar images to say quite different things, or to just mock this country’s hypocrisy, pretensions and the ambivalence of its international influence. This is the point. After all, not only can blackface have alternative meanings, it always has. Minstrelsy was never only racist just as not all blackface is minstrelsy.

Even though many attempt to project its offensiveness back into its origins in American slavery it was really in the 1960s when it began to be seen in exclusively negative terms. Call it a product of the hypersensitivities of desegregation where white guilt began to be cowed by a black resentment that defined itself by an increasing humorlessness and a perpetually furrowed brow. It was then that lines were drawn not to contain or correct a contentious history but to exert power in policing those lines. Blackface was certainly used to express love and hate and a sometimes-murderous envy towards blacks. It also expressed a profound ambivalence about a nation peopled by immigrants not yet sure what color they were or would be in the years before “whiteness” was opened to ethnic Irish, Italian, Polish and Jewish peoples.

But the open secret of minstrelsy is that it was not only performed by or for whites! Even in its earliest days many blacks cherished and claimed it. Many were proud to prove that blacks were better at performing as blacks in a time when most whites simply didn’t think it was possible! Some blacks that “blacked up” were considered cultural heroes in the fight against racism. The fact that Bert Williams––the black blackface performer who integrated Broadway––was celebrated by race-leaders like Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois and Langston Hughes attests to this. He was perhaps the greatest victim of that 1960s moment, a scapegoat for a notion of race pride that amputated history in order to exploit its own pain.

The saddest fact of this blind hostility to blackface is that it ignores the fact that African-American show business has its roots in black blackface performers and much of American popular music in “coon songs.” It is conveniently forgotten that this racist minstrel music made a black recording industry possible and was pioneered by African-Americans like Ernest Hogan and George W. Johnson, singer of the first black “hit record.” It also was at the root of American pop, from Stephen Foster to Al Jolson to Bing Crosby to Shirley Temple; the list is daunting and eye-opening. Simply put (and with the utmost respect): without Bert Williams, no Jay Z., without Steppin Fetchit, no Tyler Perry and without Hattie McDaniel, no Oprah.

So this all too prevalent idea that blackface minstrelsy is permanently a racist slur and always an assault on blacks or people of color is a troubling yet understandable one. It is far too simplistic and hinges less on the intentions of the performer or the context or even on the actual history of the form. A historically quite recent view it depends instead on an audience that has made “being offended” an expression of cultural and political power and are resistant to having that power challenged or mocked. Those who respond with such absolutism to blackface are not only hostile to the less salutary moments of common history; they are desperate to control the terms of racial conversation, here and abroad. This very American tendency, whether manifest in whites or blacks, says far more about what we have become than what we ever were.

Related Articles from The Fanzine

Darius James on black identity and zombie movies

Interview with Marco Williams, director of the documentary Banished on the case for literal reparations for land stolen from black families.