John Dermot Woods’s Love/Hate Letter to Baltimore

09.12.14

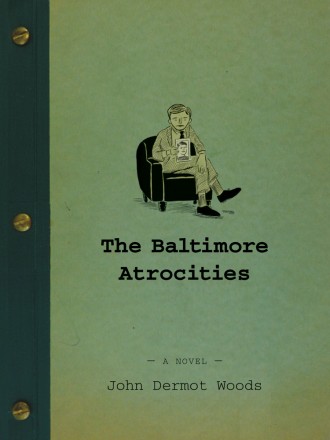

The Baltimore Atrocities

by John Dermot Woods

Coffeehouse Press

259 pp. / $17.95

My first notions about Baltimore didn’t come from The Wire, or Homicide, or John Waters’ films. They came from the Hitchcock film, Marnie. Most of the film doesn’t take place in Baltimore – yet the city is a major character in its own right. It’s where the troubled title character comes from, where her troubles began. The shots of her childhood harbor home are strangely lit, surreal, dreamlike – and so Baltimore, to me, always seemed a sort of psychosis of a city. A mental condition, a character motivation – a place you were really, really from, rather than a place you lived in.

Then I moved out to Washington, DC, and became more familiar with the city of Baltimore itself. I found it was a real city, of course, with a vibrant arts scene and a lot of character and beauty – and some ugliness, too – but that notion of a psychosis still struck me as somewhat accurate, especially when I listened to Baltimoreans talk about their complicated relationships with their home.

John Dermot Woods’s novel, The Baltimore Atrocities, perfectly captures this unsettling feeling of haunted-by-being-from, this essential, fundamental weirdness of Baltimore.

The events chronicled – or circled around, hinted at – in The Baltimore Atrocities are not your dictionary definition atrocities. But when paired with the word “Baltimore,” the second word takes on a sour, sarcastic tone – these are, indeed, the kind of atrocities that could only happen in this strange city.

In Woods’s book, Baltimore is a city of people who seem not quite to have gotten the hang of being alive. Our protagonist and his friend, who return to their old home searching for siblings who went missing years ago, find that theirs are not the only children the city has taken. Or indeed, the only tragedies, large or small, the city has created or caused. The uncertain, unreliable stories of the two main characters make perfect sense in the shifting, unreal landscape of a city where nothing seems to stick to life the same way it does everywhere else – where the same sort of rules do not apply. And indeed as the story unfolds, Baltimore becomes more and more not just a character, but a sort of sinister presence capable of harm. Our narrator tells us “the more time we spent in Baltimore, the more we came to understand the city’s unique ability to take children from their parents in increasingly indirect and unforeseen ways.”

The main narrative alternates with a series of “atrocities,” catalogued events and aspects of the city, presented almost as exhibits in the city’s own trial. But what is the city on trial for? What do the stories add up to? No one seems to know. Many of those driven to desperate acts themselves don’t seem to know. The puzzle is never quite finished – and this contributes to the unsettled, uneasy feeling the reader experiences as pages turn and the body count climbs. It’s a masterful touch, this sense of mystery created through omission. The cops don’t even understand that there’s a mystery at all, let alone how to approach it. And so, it is up to our two former Baltimoreans, each of whom has also experienced an atrocity at the hands of Baltimore, to find out what’s going on.

The main narrative alternates with a series of “atrocities,” catalogued events and aspects of the city, presented almost as exhibits in the city’s own trial. But what is the city on trial for? What do the stories add up to? No one seems to know. Many of those driven to desperate acts themselves don’t seem to know. The puzzle is never quite finished – and this contributes to the unsettled, uneasy feeling the reader experiences as pages turn and the body count climbs. It’s a masterful touch, this sense of mystery created through omission. The cops don’t even understand that there’s a mystery at all, let alone how to approach it. And so, it is up to our two former Baltimoreans, each of whom has also experienced an atrocity at the hands of Baltimore, to find out what’s going on.

Woods opens the book with an epigraph for Thomas Bernhard and “the other ghosts who haunted the places they hated to love.” And this is entirely fitting; like Bernhard, Woods tells much of his story through second and sometimes third hand anecdotes, often handed over by unreliable narrators.

And just like in Bernhard’s books, this lends a creeping, unsettled (there’s that word again) feeling to the narrative, compounded in Woods’ book by the mystery and alarming lack of evidence for these disappearances. Did they really happen? Can we trust our narrator, or his friend – can we trust anyone in this city?

And they also do something more: they humanize the horror, and demonstrate Woods’ compassion for the people of this city – both its victims and its criminals (and often they are one and the same.

In introducing one atrocity, Woods writes, “Some people fall victim to their own kindness, while some are victimized by the kindness of others.”

And so it is that in creating a catalogue of Baltimore’s villainy, he has also created a sort of a love letter – to the people struggling through the atrocities and keeping the city labyrinthine and weird and utterly unique.