Grief Lozenge

02.02.17

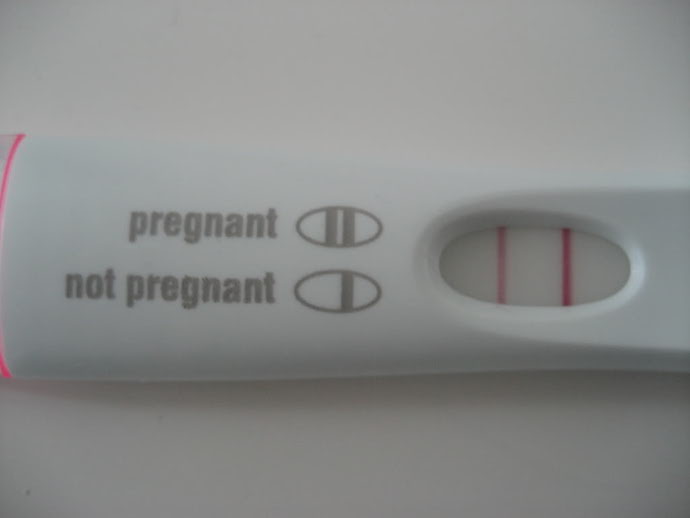

It had to have been a very early pregnancy. The line on the test showed up light. Four days later, I took another test. This time, the line was lighter than the first, but it still showed up. I searched the internet for what this could mean. My best friend told me hers looked the same. I sent the picture to her, my mother, and some close friends.

There was a new feeling that the core of my body held a deep fragility I needed to protect. My center of gravity thrummed and I laid in bed at night petting the small amount of fat beneath my belly button, as if it were a blanket tucking in the multiplying cells inside me.

The week before my doctor’s appointment, I started cramping and bleeding at work. I was stocking milk in the coolers, organizing them by date. Skim on top, two percent in the middle, whole milk on the bottom. About a dozen eggnogs had gone out of date, they littered the floor behind me. In the bathroom, I watched blood as it streaked through the water, and cried out of fear.

On Thursday, I showed up at the county clinic, feeling disoriented and hopeful about what I might find out.

Everyone at the clinic was very nice. I had no health insurance and got nervous that maybe I wasn’t being told up front what the cost of the services might be. I filled out some forms indicating my income level (currently below 12,000 a year) and signed several documents indicating that I would have to show proof of income regarding my wages in order to be considered on a sliding scale basis.

“Do you have two recent pay stubs?” the receptionist asked.

“No,” I said. “I only got my first one on the ninth of December. I can show you the second one when I get paid next Friday.”

“Okay,” she said. “I’ll just make a note in your file that they will have to extend the seven day period for you. Are you on Medicaid?”

“Not yet,” I said. “I applied two weeks ago.”

“That’s good— they can also get you set up here for applying if you need it.”

“Well, I guess I was kind of confused,” I said. “When I applied, they told me it would take 120 days to process my application, but I’m pregnant now, so I’m not sure how that will work.”

“Yeah, that is definitely something to ask them,” she said. I felt embarrassed. I thought about going back to the county health department, taking a number, waiting in line just to ask a question. I learned later from the nurse that I was allowed to check up on my application in 45 days, and sometimes Medicaid will backpay up to three months of care. I learned that, if I reapplied, they would consider my case “broken” and have to wait even longer to receive care.

When the bleeding started, I felt similarly lost. At this point, I thought, I won’t even need a doctor. The baby (fetus, embryo, insect?) is gone. What if they were going to charge me for this, and I would have to pay half a month’s rent out of pocket just to be told I’m not pregnant?

The doctor’s face was warm and welcoming, with clean skin and natural looking makeup. She looked young, but mature and well-put together in a way that made it seem like she was the type of person to wake up to her alarm on the first go and never hit snooze. In front of her she placed a sheet of paper with the date of my last period written on it, and then the dates of my positive pregnancy tests. When I told her about the bleeding, she wrote down the dates for that, as well.

The urine sample came back negative. The doctor’s eyes moved from the paper to look directly at me, and as she did, I moved my eyes towards the paper so as not to catch her gaze. I could not look directly at her when she told me the results of the test. Images of handmade blankets and baby clothes my friends promised to make floated out of one darkness and into another. The voice of my husband telling friends the news trailed a distant echo through my ears. Only my mother knew about the pregnancy, she was waiting for my okay before she could tell everyone she knew. I imagined telling her about the loss, the tiny bridle inside of her slowly dissolving like a grief lozenge.

I did have two positive pregnancy tests. At some point in the past two months, I had to have been pregnant.

I ended up asking too many questions. The doctor seemed rushed, and answered my questions very tersely and quickly.She would not confirm or deny that I was pregnant at all, but suggested that it could either be a very early pregnancy, or that something else was going on. The doctor determined that the next step was to have my blood drawn.

“If you’d miscarried, you would still have pregnancy hormones in your blood,” she said. “We can test the levels.”

To me, it was odd that no hormones showed up in the urine test. She insinuated, using the general “you,” that I didn’t take the tests correctly. I didn’t understand what could be so hard about peeing on a stick. I have never had a false positive in my life, and have always taken pregnancy tests the same way. She then seemed to correct herself by saying that most urinalysis pregnancy tests aren’t accurate at all, that it can’t detect hCG levels if it is a very early pregnancy, as one example. These levels are supposed to double every day that you are pregnant or something like that, which is how they determine just how pregnant you are with a blood test.

The nurse placed a tourniquet around the upper part of my arm and I marveled at the ease of which he “tied me off.” I thought about doing intravenous drugs, though I had never done them before in my life. He took my blood and as it always happens when I get my blood taken, my head stretched into a crescent moon and I felt woozy. I tried not to think of the way that blood was leaving my body, did not stare at the tube of it when he removed the needle, which I had become accustomed to doing years before when I was testing for an endocrine disorder called polycystic ovarian syndrome. I’d always been fascinated by seeing the inside parts of myself move to the outside, especially the parts that bled.

Before the appointment, when I was cramping and passing tissue from my body, I spent a lot of time staring at the red fibrous pieces in the toilet, wondering if the pieces contained a thing I created. I realized that this was a redundant idea because my body creates tissue every 28 days and passes it anyway. I didn’t know why it seemed like this time, it was more depressing, or that there was a deeper sense of loss.

Christmas was coming up, so I’d preemptively bought both my parents coffee mugs that had cute phrases about becoming grandparents on them. My own grandparents had died recently, and the idea of giving the gift of grandparenthood to a father that had lost both his parents within two months, and to a mother that had neither parents for a very long time, somehow held meaning for me. My grandmother had been ill for a while and requested that no funeral would be held. The details of her death have been kept purposefully far away from me — so far, that, when my grandfather died about 50 days later, and my parents decided to hold the double wake, they scheduled it in my father’s hometown of Rochester, New York when I would quite literally be across the country in Washington State on my honeymoon with my new husband. Everyone that had ever affected my young life would be there, all of my American relatives. And yet I would not be able to go.

Losing my paternal grandparents felt like severing a legacy from my body because while I did not lose the memories of them, their estate was cut up and sold in pieces. I offered to help my father in the process, but he did not involve me. I felt (and still feel) that the grieving process had been chosen for me. I was not at the wake, did not see them, dead or alive or ashes. I only heard through phone calls what had happened. My family is not the sharing type. The house my grandparents had owned for much of their marriage of sixty years was also sold, and I never got to see it before it went. As a military brat, I don’t really have a hometown or a sense of belonging to any particular place, except for where my paternal grandparents lived. I remember eating fresh green beans from their garden (not canned!) for the first time in my life. I remember bathing in the lavender porcelain tub that my dad and uncles grew up with, the broken tile pieces at eyes’ height that had been covered with clear scotch tape, revealing the darkness of the space between walls. The penny stamped into the linoleum floor of my father’s childhood room. I offered to buy the home, when I still worked in an office and made a decent amount of money. For the price it was being auctioned for, I could have paid the mortgage and still paid rent on my apartment in Denver. I could have held the only land my family still had. The house was instead sold to someone we did not know, an airplane pilot, for $65,000.

A lot of their belongings, the inexpensive, useless stuff that I’ll never see again, like my grandmother’s vintage vanity mirror or the 70s-orange coffee thermos my grandparents filled up with coffee every morning, felt like symbols of them. Proof that they had once existed somewhere outside of my mind. Death is so immediate— in the sense that a person is here and then they are not. It is an absolute purging of their existence, except for the objects they leave behind which for me was a type of cementing of their existence. I can’t possibly remember everything about a human being. I can carry that memory within an object I imbue with meaning, however, and somehow feel as if I haven’t forgotten, as if my memories of them aren’t slowly fading as I age.

The day that I miscarried, I took a long bath and sobbed silently in the water until the water became too cold to inhabit. Then I spent the rest of the day laying in bed until I could feel something move far enough down within me that it needed to leave my body. I passed particularly large clots of material. One floated to the bottom of the toilet, heavy, dense. It was large. In the water, it looked to be the size of my palm. Something in me thought maybe it was more than just a red, bloody clump of cells. Maybe it was a red, bloody clump of cells that had already started to self-organize. This seemed important. Mournful. I stared at the lump. I took a picture of it with my cell phone. The water was clear except for the blood. I wanted to keep it and bury it. Something had been living in me and now it was dead. I reached into the water. It felt rebellious, childlike to put my hand into a toilet, something very taboo and strange and perhaps something you would only see in art films, in strange porn or on Liveleaks. I grabbed the clot and held it in my hand. Blood leeched from around it through the grate of my fingers, like sand, only viscous. The clot was suddenly much smaller, perhaps the size of a silver dollar.

I stared at it. And then I wrapped it up in toilet tissue five times one way, and five times another until it was a white, fluffy square the thickness of a menstrual pad.

I suddenly became very aware of how strange it would look to my husband to leave the bathroom with a large square of tissue holding human (fetus, embryo, insect?) remains in one hand, and a garden trowel in the other. In fact, I could not be certain that this particular clump was remains of anything, and began to feel insane. The two weeks that I knew I was pregnant, it was easy to think of the thing inside of me as a ‘baby.’ But was it? It had been cells. Blood. A wad of chewed gum stuck to the wall of my uterus, waiting to be eaten alive. We lived in an apartment, and I did not really want to bury it somewhere impermanent. Was I even pregnant at all? Did I just grab period blood and wrap into tissue to bury it like a lost pet? I saw both positive tests, even if they were very light. A false positive is very rare, and it seemed like the more I stroked the small potbelly that was growing (from binge eating sugar or being pregnant, who knows), the more that I felt protective of this small space within me, of what could be just four or five cells, a kidney bean inside a sac of bloody jello.

I felt, with certainty, that I had been pregnant before. And I felt, with certainty, that something had been lost that day. That something was happening to my body and it was scary and there was nothing I could do to stop it. And now, in the doctor’s office (too late? But nothing could have been done anyway) I felt, with certainty, that I just did not feel pregnant anymore, the way that I had the week before. My hands cradled my belly during the week between the bleeding and the appointment, and I just did not know if I felt connected to it anymore.

After I wrapped up the bloody clot, I sat on the toilet and searched for images on the net about spontaneous or intentional abortions, and what the leftover matter looked like at each week of development. At seven weeks, I found a picture of a latex-gloved doctor hand stretching membrane-y clear and red tissue across the fingers. I found forums upon forums of women asking, over and over again, about whether or not they could still be pregnant after bleeding and passing blood clots. One woman would post a question in the forum, and then for five, nine or 12 pages other women would pour in, sharing their same experiences, posts upon posts filled with anxiety about their bodies and what was happening, all asking questions, all lacking answers. I was surprised to find that I had a profound lack of knowledge in the biological processes of my own body, and it seemed like I was not alone in that.

There were also a few YouTube videos of women that had explored the things that had come out of them when they miscarried. A few had the embryonic bug-like masses, no bigger that the end of a thumb, suspended in water inside of a small jar or plastic bag. The forums suggested that exploring what’s ‘passed’ can help determine whether or not you have miscarried— for example, if it is a gestational sac, you will most likely find some kind of grey or pinkish matter inside of it, depending on how far along you are. Some also suggested they even found the amniotic sac, sitting like a clear paperweight in their hands, the fetus inside.

The video that struck me most was one of fetal remains from a miscarriage that occurred at 14 weeks. The fetus (baby?) was about the size of a lemon. Whoever it was, they were outside filming. The hand seemed to attempt to caress the fetus it was holding, which gave it the effect of looking like it was still alive, twitching, reacting. The video was only a minute long. It seemed strange to record these kinds of things, but I took the picture of my toilet. Maybe what we are doing when we record these things is somehow trying to cement the idea that this living thing did exist, and that we want to record it, archive it, since it left before we had a chance to understand it. With a loss like this, there is no real object we can keep to cement the memory in our minds. Victorians took photos of their deceased, even made jewelry from their hair, and mourned very publicly and formally through dress and behavior. With a loss like this, the cultural norm is to not discuss it at all, to treat it very privately, as if it is a mistake, not supposed to happen, a grieving error. It is natural to want to ritualize loss, no matter the kind. I grew attached not just to the embryo within me, but to the idea of being pregnant, what it would mean to grow and then deliver a child. I was grateful to find the kind of desire that would push a person to publicize a loss, no matter how odd or sad. It made sense to me to attempt to archive an event like miscarriage, given that there is no material we can safely keep of what remains, if that is what one chooses to do.

I thought about the clot, and I placed it in the linen closet where it could not be found.

I had only told a select handful of people that I was pregnant, without announcing it too publicly, so when I told them about the bleeding, and the blood test, and the negative pregnancy test, they then followed up asking me about how I was doing. I think people lie because they don’t want the world to be as terrible as it is. I’m not sure if I lied, because I did feel okay. I mean, I was alive. But I also felt a sense of grief that I didn’t think I deserved. Especially since I had never heard the heartbeat of the thing, especially since I’d started to convince myself that maybe I did piss on the test wrong, and that I had never been pregnant. Perhaps the idea of feeling pregnant was tied up in a miscommunicated intuition that I thought I had with my body. Thinking about it makes me feel tired, and in subsequent days I began breaking a lot of expensive, almost irreplaceable things on accident— because I wasn’t being attentive, because I was rushing through tasks— and then berating myself for being so clumsy. The negative self talk got worse. I told people that I was okay, given the briefness of the theoretical pregnancy, and that I was looking at the loss from an anthropological sort of viewpoint, in terms of how or when it is okay for a person, man or woman, to be sad in public. But really, saying that allowed me to have distance from expressing how I really felt, because I know that death makes people feel uncomfortable, especially death involving pregnancy or potential children, and being accommodating is a social tool used to control the way we express emotion to each other.

When I first was pregnant, during my internet research I saw a lot of suggestions from these “mom to be” type websites suggest not announcing until the second trimester, when the risk of miscarrying is much lower. On one hand, I can understand that it might personally be hard to discuss the loss of a pregnancy with everyone you know, which is a good reason not to announce so early. On the other hand, it seems like this practice really shields expectant mothers from the reality of pregnancy, which is that miscarriage is common, and most of the time, is not the fault of the mother. How common miscarriage is, is often hard to say, since many first pregnancies can result in miscarriage so early on that the mother may not even know that she is pregnant.

After my visit to the clinic, I began blaming myself for the miscarriage—even though logically I knew that it couldn’t have been prevented. The week before I took the test, for example, I drank heavily at least three times, and had been smoking cigarettes when I was drinking. I drank coffee with chicory in it at my friend’s house one day, and large doses of chicory (so says the internet) are rumored to cause uterine contractions, inducing miscarriage or early labor. I was taking 400 mg magnesium supplements every other day, when I read somewhere that the daily limit for pregnant women should be 350 mg. Even the idea that I didn’t pee on the pregnancy test in the right way had caused me to doubt myself. In the doctor’s office, I wondered if I hadn’t miscarried how many choices I’d make throughout the rest of the pregnancy that would be examined this hard, by myself or others, or what I would be held responsible for. If and when I do have a child, it is true that my choices, even after birth, will be scrutinized, whether or not I use cloth or disposable diapers, whether or not I leave my child in the car while I run into the gas station, whether or not I use daycare, whether or not I work part-time, full-time, or not at all. Even if the pregnancy was unwanted and I chose to end it for whatever reason, I wonder what kind of grief I would be allowed to feel in this moment. The beginning of pregnancy is an unstable place, an amorphous and constantly changing fluid in the structure of the body, a syrup in the mouth heading to the bloodstream.

The doctor did not call me back the next day like she said she would, and when I called she had left for the day, a Friday. I waited over the weekend, and had convinced myself that the square lump of tissue paper in the linen closet was really nothing, just a wad of blood. I threw it away into the trash. I was hopeful. Or really, I was trying to rid myself of the regret I might feel, had it been a living thing and, even though it was dead, I just threw it in the trash instead of somehow ritualizing its loss. I wondered if I was losing the chance to grieve properly, or if treating the wad of tissue as worthless was how I should be grieving, to tell myself that miscarriage at such an early stage shouldn’t be devastating.

I called again on Monday afternoon when still, no one had reached out to me. Finally, a receptionist found a nurse from the prenatal department to talk with me.

“Okay, Mrs. Nash,” she said. “The doctor wanted me to tell you that your blood test came back negative, and she recommended you come in for a well-woman exam and a check up, if you are still trying to get pregnant.”

“Does it say what my hCG levels are?” I asked. At the very least, I wanted to know how high they were, so I could research online just how far away I was from the pregnancy, or to see how quickly the hormone was leaving my body. Was there any hormone there at all? What did negative really mean?

I heard the shuffle of papers over the phone.

“Unfortunately, I cannot see that on the results here,” she said. We spoke our goodbyes and hung up.