BARTHOLDI

01.02.17

Lenny Bartholdi first made a splash in the literary world when he hacked into North America’s largest publisher, W.W. Norton & Co, and inserted himself into the Norton Anthology of Poetry (5th Edition). He’d timed it like a bank heist, and before anyone could discover the sabotage, two hundred fifty thousand copies of the anthology were on their way to every high school and university in the country.

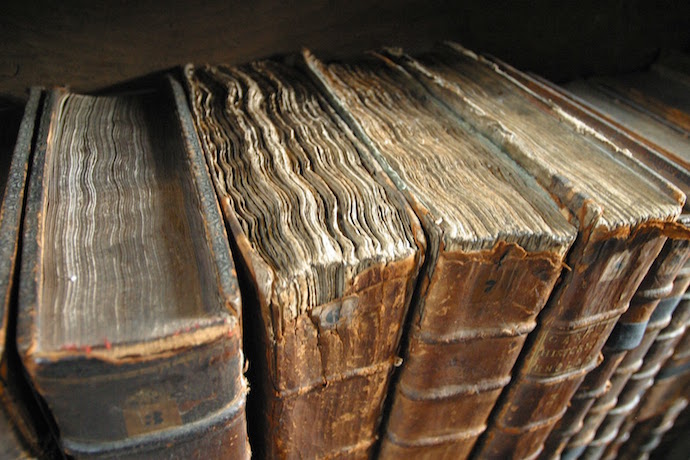

The classroom standard for the teaching of English verse is a cathedral of the language, and tours start at the catacombs of Anonymous Poets. At the base of the Great Stair, the visitor glances at the tombs, then looks up to where Caedmon’s Hymn is fastened in magnificent stained glass. She climbs and ponders Ubi sunt qui ante nos fuerunt as the Hymn’s burning colors flitter like buttorfleogan across her ascending face. At the Mezzanine, she slows her step to admire a fresco cycle illustrating the greet estaat of Geoffrey Chaucer (b 1343) and then it’s on to Statuary Hall, to bestow dainty kisses upon likenesses of Sir Walter Raleigh (b 1552), William Shakespeare (b 1564), and John Milton (b 1608). After the William Blake (b 1757) Mirror Maze, it’s out to the arboretum memorializing Wordsworth (b 1770), Coleridge (b 1772), and Keats (b 1795). Next, a composting and renewable energy center celebrates Walt Whitman (b 1819), and behind that, the Emily Dickinson (b 1830) apiary with free honey tasting. Back indoors to the Library, the visitor paces creaking floorboards in the rooms of William Butler Yeats (b 1865) and T.S. Eliot (b 1888) until, smoothing her hair with her hand, she proceeds down the gyring stair to the Gallery, and its tributes to Elizabeth Bishop (b 1911), Robert Creeley (b 1926), and Charles Bernstein (b 1950). Exhausted and bleary-eyed, she welcomes the cool breeze promising egress and rest, and hardly notices the Greg Williamson picnic bench (b 1964) on her way into the world. She breathes deep, believes she’s in the clear, turns the final corner –she turns page 1350 — only to be startled and sickened: a monstrous colossus rises into view, like a dementedly grinning Statue of Liberty: Lenny Bartholdi (b 1994), represented by three poems.

Confronted with that vandalized printing of the great book, Merit Scholars and members of the National Honor Society may have noted that Mr. Bartholdi went by Lenny and not Leonard, and that he was the collection’s junior poet by a full 20 years. Yet even those repeating Sophomore year couldn’t help note that LENNY BARTHOLDI was printed in block letters ten times larger than the other names. And, not only was it printed ten times larger, it was also printed in red –-incandescent and eye-searing. And, not only was it printed in red, the red was in flames –like it belonged on the side of a monster truck. And so it was: the enormous red name of LENNY BARTHODLI flamed across page 1351 like a literary apocalypse.

And at the very bottom of page 1351, condensed like a diamond pressed from the burning name above, a small couplet: two mere lines of Mr. Bartholdi’s poetry –so vulgar and unforgettable that no student, however sophisticated her apathy, could ignore it.

Nor could any student ignore what came next, on page 1352, where Bartholdi’s second poem sprawled in a motley font reminiscent of a ransom note, unfolded to poster-size, and narrated in unbalanced and intense verse a battle between Bartholdi and the unused fraction of his brain.

And yet it was the scandalous, borderline illegal Third Poem that nailed it. Printed in two-point font, it was illegible without a magnifying glass, and the gimmick did the trick. For the first time in its many printings, the anthology’s most widely read poem was not “Kubla Kahn,” or “Dover Beach.” It was, alas, Bartholdi’s unbeholdable and brain-destroying Third Poem.

As the good people at Norton Publishing read the Bartholdi poems, line by incomprehensible line, not in proofs but in complete, $70 printed copies, their disbelief mounted step by enjambed step until the words before their eyes hustled and scurried like ants on the page. And when they came to the Third Poem and applied their eyeglasses, those ants popped, hissed, balled, and died. In sympathy, the stricken editors one by one curled into the fetal position, as if doing the opposite of the wave.

Then there were those who proposed Norton stand by the poems and thereby supersede Bartholdi as the true literary innovator. The radical act is not knocking on the door of the canon, they argued, but opening it. By admitting the poems, the 5th edition would go down as an undauntable experiment, and Bartholdi would be relegated to a footnote of thwarted artistic ambition.

They were all fired. To an outraged conglomeration of school-boards, booksellers, and social justice organizations, W.W. Norton & Co. explained the circumstances of the “loathsome intercalation,” and cooperated with authorities to identify “the imposter” and ensure he serve a sentence in line with that of the most promiscuous counterfeiters. There were even some at Norton who believed that was stopping short. In their opinion, Bartholdi was not a counterfeiter, but a Terrorist, and the Bartholdi Sabotage was literature’s 9/11. “We must respond,” went their refrain, “We will respond.”

Norton’s response, when it came, was that books must be in their original wrapping to be eligible for return. In the case of already unwrapped copies, it was suggested that teachers exclude pages 1350-1354 from any curriculum and consider “the physical excise” of the offending pages.

Few teachers read the memo, and fewer still took it upon themselves to mutilate a brand new textbook. There were even those who were happy for the controversial material. And so, one way or another, the great majority of the 250,000 Norton Anthology of Poetry remained intact, its canonical trajectory culminating with Lenny Barthodli’s 75pt name and three psycho poems.

*

Only weeks later, Bartoldi returned to the scene of his crime, and this time targeted The Norton Shakespeare.

He found entry more forbidding than before, but he was devious. He passed through twists and turns which reminded him of the very Bard’s syntactical elaborations, and down chutes evoking the Poet’s undulating articulations, and many times he risked falling, as did Shakespeare each time he entered new personae. Bartoldi landed safely on his feet, felt his way to a myriad-minded portal, and suffered its every transformation until his penetration complete. For the first time since Boswell’s Third Variorum, editorial footsteps echoed in that Sanctuary so chambered and reverberant that repercussions preceeded and proceeded every footfall.

When he stepped out of that keystone tome, it was more weighty than ever, for it included a “New Authoritative Introduction by Lenny Bartoldi” in which he navigated the student along a system of footnotes toward a truth “as turbulent at first glance as it is placid upon reflection.”

“And yet is it more or less remarkable,” the introduction read, “That Shakespeare’s plays are a composite labor rather than the work of one man? Great authors are of our own making, and if we learn from The Shakespeares, our greatest authors lie ahead of us. All that remains is to ask which writers will be the next to put aside the authorial ego. Who will be the next to band together to write a book none alone could write?”

That was August. In September came a new edition of the Selected Allen Ginsberg which included only seven poems. Next, a new printing of Plath’s The Bell Jar contained only two poems, but over one hundred twenty photographs. And a new O’Hara was not only fractional in size, it also contained a prescient manifesto titled IMPERSONISM.

If reading was like swimming in the ocean, said one blogger, Bartholdy had equipped the reader with a mask. The colors changed, the light became wavy, and it was disorienting at first –but under the water’s surface, a whole new world was revealed: colorful, strange, and beautiful.

*

It was revealed the blogger had been hacked, but nonetheless, things were different. Bartoldhi’s career was in one respect, however, similar to that of other writers: after first establishing himself as a poet, he moved to prose. New books by Jonathan Safran Foer and Dave Eggers, published in time for Black Friday, were noteworthy because critics found within them something worthy of praise. Of course, the explanation was not long in coming, and the victimized authors were left no choice but to affect displeasure, even as prize nominations mounted and royalties poured in.

When PEN, the Man Booker Prize, and the National Book Foundation came forward to announce that their nominations were the result of Bartoldhi hacks, few were surprised. But when reporters revealed that the nominations were in fact legitimate, and that it was the series of retractions that constituted the true work of Bartoldhi, people began to simply give up.

That December, Poetry magazine published an essay by Jessica Reed. The essay read:

As we integrate quantitative analysis into traditional literature studies, exchanges of thought evolve into exchanges of matter, and immeasurable ideas congeal into measurable things. In this new and material economy of literature, the notion of a literary value independent of commercial value is a fantasy. The best metric by which to know a book’s value will be book sales; in fact, book sales will not merely measure value, it will express that value perfectly, and to the question, “what does that book mean?” one will be answer: “475,870.” The New Canon, then, will consist of the world’s all-time best-sellers, one after another.

In Bartholi, however, we have a champion at last. Subverting the model of writer-as-content-provider, he does not provide content but changes it. He does not aspire toward virality, but rather writes books people want to destroy. His best-sellers are unbuyable books everybody bought already, and never to be sold again.

Upon the appearance of the essay, Reed was outraged, but the buzz surrounding Barthoji continued to grow until he attracted such swarms of imitators and so many clouds of forgeries that by the New Year, Barthoji’s own works were in danger of being consumed by a voracious authorlessness which spread through the literary world like a plague.

But just when the virus threatened to eat away the last of literary identity, Barthoji managed to separate himself from the tangle of attributions, appropriations, and claimants to the ‘True Barthoji,’ and continued his singular pioneering.

First it was the SATs. Proctors had never heard so much cheering. Then it was the written portion of The Department of Motor Vehicles’ driver exam, which included a series of questions under the heading Reality and Representation.

Then came cookbooks whose recipes were distinguished not so much by being unsavory, as by being impossible to execute. Then the Peterson’s field guides for humans, classifying the species according to clothing, elocution patterns, and behavior. Then biology text-books that read like some Lamarkian fever dream, physics volumes that quoted from the Upanishads, math books written as British satire, and chemistry texts which were all too empowering.

Then came The Bible.

*

“If it had been the Koran,” Christians protested endlessly, “If he had hacked into the Koran,” they fumed, “If he had changed the words of Muhammad . . .” staggered by the thought they could not complete, they worked to summon the outrage such an act would surely have occasioned, never mind that Baltholdhi had in fact hacked into the Koran (changing a single “in” to “on” and creating a new split in Islam).

For all the uproar, Baltholdhi’s Bible was mostly innocuous. Other than elaborations upon the Books of Job and Ecclesiastes, and a recasting of The Psalms into Ted Berrigan Sonnets, his only prominent change was the insertion of a new book into the Old Testament: The Book of Minor Prophets II.

Written in a combination of Hellenistic and Achaemenid styles, the Book mostly offered financial advice, but it also narrated histories of celebrities, evidence of time travel and extraterrestrials, and visions of literary utopias. Baltholdhi himself did not write The Book, as explained in an open letter to Guideposts, he merely edited it. He had always wanted to edit a literary journal, and this was his divinely inspired format by which to introduce America to six of the most important writers working in the language today.

As collectors and other interested persons rushed to religious and secular bookstores to buy up all the Bortholdy Bibles before Thomas Nelson could execute their recall, Christians filled the streets. In Washington DC, hundreds of thousands filed out of busses and rallied. Protestors formed a human chain around the White House. Subways and roads were blockaded. Tear gas swirled among helicopter blades. The Protestors lit fires and chanted, demanding an audience with the President. And the world learned of the first major literary movement of the 21stcentury, The Minor Prophets.

The crisis grew. The Times prefaced their coverage of events with the announcement they had gone back to moveable type and ink rollers to protect themselves from any possible “Barkholdi infections.” The announcement, however, was widely regarded to be another hack. Politicians caught on, and when quoted unfavorably simply claimed Barkholdi had changed their words around. Across the country, manipulated news proliferated in newspapers and websites: obituaries of the living, wars between allies, and specious anthropological finds were described serially and in academic detail. Markets crashed after rumors went flying that Barkholdi was spoofing stock prices. And the revolutionary poetry of the Minor Prophets was shredded by an overdrive news cycle toothed with catastrophe.

It wasn’t just the Minor Prophets. Brjolki’s poetry, his introduction to Shakespeare, his novels, his standardized tests, they all fell to the wayside (only some cookbooks remained in the public eye, as culinary bravehearts endured the recipes and discovered tastes that changed cuisine forever). Jessica Reed rewrote her essay on a typewriter, photocopied it, and mailed it around. In her summation, Brjolki was not only imitable but imitability itself. He was not an author but authorship and specifically celebrity authorship that writes for the sole reason of being read. Brjolki pre-sells works written to sell by writing what readers think others bound to buy, then, boasting how much he sells, sells more. The fact he doesn’t receive money from the sales means he is beneath even the profit motive. In Brjolki, the most humane elements of capitalism, such as self-interest, are absent, and only the mechanism of capitalism remains: pure spreading. A boundaryless incorporation which admits no difference, where form from content is as indistinguishable as content from content and form from form. Reed’s analysis became consensus. All the critics agreed: Brjolki reduced a spiritual world to materiel.

*

Sitting at his desk, a letter opener beside his Olivetti Studio 44, Lenny Blarjuldi read the essay with satisfaction. If the essay had been published in Poetry magazine, Reed would have been right, of course. But, hand-typed, post-marked, and with a return address, her argument was a parody, and he told her so in a brief and polite letter written to encourage correspondence. And he imagined all the other letters Reed would receive, and the letters she would write back. And he looked out his treehouse door to the stars, and imagined the Blorjuldi-proof poems being mailed among friends, the Blurjuldyproof stories bandied between rivals, the Blurujuludy-proof theories contested in bars and basements, and he felt satisfied indeed.

And when it was all over; when the Norton, the novels, the Poetry essay, and the rest were buried under a morass of frauds and counterfeits, then he undid all his work –-not that it much mattered, but he liked to cross his T’s. He recreated a world where he need not have hacked into anything, or had to have hacked into all of it and he did, or he just entered this –hard to tell. Still, seems there’s a little Brlujdulti in everything, doesn’t it? As if once in there, it can’t come out. Not even with a typewriter.

He was very satisfied indeed.

———————

Eric Gelsinger is an ex-pat from Buffalo who currently lives in the Osa Peninsula. He is a translator and poet, and he’s just completed two poetry novels. He is also the editor of Poets’ Fiction which publishes fiction & translations by poets.