Donnie Darko

29.10.18

On October 31, 2018, I let Frank come into my apartment. Until Frank, my apartment was a shield, a vest no bullet could penetrate, but because he wore all black, and deodorant that smelled like a high school locker room, and grinned in such a way that calls to mind the verb “to groom”—and because he was married but did not wear a ring; because he possessed a seductive, flat affect; because he used wheatpaste to inspire the populace to rise; because he had fine taste in contemporary sculpture; because he purported to be a fiction writer while, in fact, he wrote nothing beyond sexually suggestive emails; and because he attended Zen meditation regularly, asked questions about my emotional landscape, cared for a few houseplants, and did not tell me about his wife until four months into our friendship—I drank two glasses of wine with him in my living room and made small talk, and came to terms with the inevitably of certain unethical events to come.

“Do you like Joy Division,” I asked Frank, pointing to an Unknown Pleasures poster across the room. The historical reference to concentration camp brothels in juxtaposition with his extramarital encounter was not lost on me. As I sat on the couch with Frank, succumbing to each necessary step leading to sexual intercourse (the red wine, the wide eyes, the pillar candle, etcetera), I thought about how I wished I had married my ex-partner of twelve years when he wanted to marry me, and how, if we had gotten married, I would have worn my Unknown Pleasures t-shirt to the tenth floor of City Hall on the day of our elopement. There, one half of a gay couple waiting to exchange their vows would have made an allusion to the first song on Unknown Pleasures, “Disorder”—“On the tenth floor, down the back stairs, it’s a no man’s land,” one of the men would have said—and I would have experienced the spirit moving through me, though I would have been unable to metabolize the feeling.

Until Frank entered my life, processing my feelings was impossible. Sometimes, they were ambient, like a record I chose from a shelf and placed on my turntable, to which I would listen while lying in bed with my eyes closed. Other times, they were floating sheets, ghosts of ghosts of ghosts I did not know I knew, and so I could not touch them. Always, my feelings were concentrated, and I would think how nice it would be if a diffuser existed for them: I would put drops of my feelings into it like essential oils, and they would spread into thin air.

Frank, a two-way mirror, introduced me to my rage. Looking into his eyes, I would not see myself, but rather a camera filming me, dutifully projecting my gaze back onto his face’s disembodied monitor, so I too appeared inside the monitor, where I would present my palm back to my own gaze, which I pressed to the screen of Frank’s face. When my palm touched Frank, time rippled. Then Frank would gaze at me, his teeth situated beneath his ears, and pressed back. “How can you do that,” I asked, to which Frank did not respond.

A website devoted to demystifying everything explains that there are five ways to determine whether a person in front of you is a two-way mirror. First, you must observe whether they are hanging on a wall, or whether they are part of the wall itself. If a person seems to be part of a wall, there is a good chance they are two-way. Second, observe their lighting. Look around and consider whether their light is extraordinarily bright. Next, consider where you are. Note that it is illegal to become a two-way mirror in private spaces; however, in several states, it is legal for dressing rooms to contain surveillance cameras. Finally, do things like: tap on the surface of the person; place your fingernail against him; or, consider the extreme act of punching his face.

As I recall having unprotected sex with Frank—his decision, not my own, although a person generally possesses some agency in the situations into which she gets herself (and I had gotten myself into this, I convinced myself)—I thought of violence, sexual slavery, the replacement of dead women with more soon-to-be-dead women, and Joy Division’s song “No Love Lost,” which appropriates language from House of Dolls, the 1955 novella by Ka-Tzetnik 135633, a prisoner held at Auschwitz:

Through the wire screen

The eyes of those standing outside looked in at her

As into the cage of some rare creature in a zoo

In the hand of one of the assistants

She saw the same instrument

Which they had that morning

Inserted deep into her body

She shuddered instinctively

Daniella—the protagonist in House of Dolls—and other women in the Joy Division ultimately have organs removed from their bodies. These organs are depicted in the book as missing pieces of the women, hearts floating in jars in doctors’ offices, “uprooted chunks of life” that will go on living, while the gaps in women’s bodies are replaced by artificial parts.

Before my 20 minutes with Frank was up, I too had a heart.

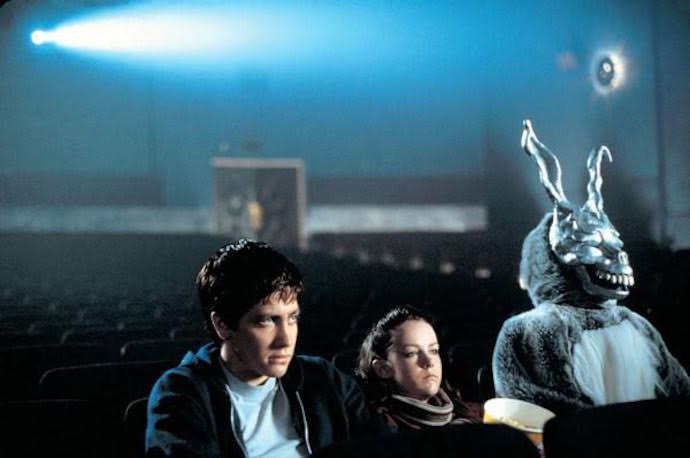

Before we had sex, Frank and I kissed. I used my tongue; I gripped his neck; I became liquid; then I got scared. Frank’s eyes were white; his ears were long; his teeth occupied too much space on his face, extending from the uppermost quadrant of his left jaw to the uppermost quadrant of his right. His forehead glistened, covered in veins. Fear, which coursed through my body, caused my heart to sound like a warning bell, but although I heard it, I ignored it, much in the way a person who hears a fire alarm going off in the background of her life tends to disregard it. What was it—my heart—trying to say? Abruptly, Frank took off my pants, then his, then looked into my face, filming it. Why are you wearing that stupid rabbit suit, I thought, and my heart no longer thumped in my breast. Rather, it was now pounding in the narrow bed. “Why are you wearing that stupid woman suit,” Frank said. To which I said nothing.

In lieu of further narrating this scene, I will now describe what I should have done instead of what actually happened. Life’s central questions are typically ones of fantasy versus trauma, and in this case, I possess enough self-confidence to assert how I should be the one to rewrite my fate. Therefore, it is with a sense of retribution that I state how, after he called me a stupid woman, I turned Frank over onto his back, then stood up on the bed, then stood up on him, and crushed his sternum. Indeed, I lifted my left leg onto his body first, followed by my right, and placed all of my weight into the moment. When Frank was no longer breathing, I took one of the medical instruments in my house—a scalpel blade—and drew a heart over his chest. Perhaps I should have extracted it right then and there, but instead I took a large houseplant potted in terra cotta and cracked it over his skull. Imagine! A man bleeding in bed from a blow to the head via a houseplant. I laugh thinking about the image of Frank’s blood intermingling with soil; soil staining my white cotton comforter; the white cotton comforter forgiving itself for being part of the scene. Then I imagine I put on a record—there are always so many to choose from, but I chose Unknown Pleasures; I always choose Unknown Pleasures—and tied Frank’s hands together in front of his navel using kitchen twine.

After the scene, I call my sister and cry. I am alone in the living room, sitting under strings of Christmas lights, un-showered, once again wearing pants. I can feel Frank’s ego inside me; I can feel him entering my apartment. I want to rid myself of him but do not know how; I want to dispose of his body but know it is already gone; I want to write down the facts but know there are none. I also desire to make a gynecological appointment and do so using an online scheduling platform, although it is Halloween, and I am supposed to be at a party with my friends, where I will eat a chocolate chip cookie with butter in it, despite the fact that I am dairy-free and do not know where the cookie came from. Did Frank’s wife send it to me as a form of punishment?

As I cry on the phone, I stare into my laptop, refreshing Frank’s social media page, where there exists no trace of his wife—Frank’s poor wife—and I think about whether I too will one day be married to a man who moves through the world without a ring. Then I think about whether I will ever have sex again, and in this moment, it does not seem like it, although it crosses my mind that sex is included on Maslow’s hierarchy of basic needs. In fact, a friend recently told me, two male twins once had sex with each other because they needed it. So what if I did too? My encounter with Frank felt like consumption, an infectious bacterial disease characterized by the growth of nodules in the lungs that causes approximately three million deaths each year in developing countries. Its spread is combatted by vaccination and the pasteurization of milk, but I am dairy-free; I identify with cows. They roam pastures and are sacred in certain cultures, but are also victims themselves. I know this because I attended high school with boys who drove to barren fields to tip them over.

Sometimes, men try to impress women by saying they’re vegan, and by noting they don’t drink cow’s milk due to rape. Is Your Food a Product of Rape? reads the title of a subpage on PETA’s website. So states the website’s copy: Cows produce milk for the same reason that humans do: to nourish their young. In order to force them to produce as much milk as possible, farmers typically impregnate cows every year using a device that the industry calls a “rape rack.” To impregnate a cow, a person jams his or her arm far into the cow’s rectum in order to locate and position the uterus and then forces an instrument into her vagina. The cow is defenseless to stop this violation.

I am thinking again of Frank, a vegan with whom I, in fact, had three unfortunate encounters. The first time, on Halloween, I cried, and the second time, I bled. The third time, a friend had recently died, and I could not feel my body. I remember the room was cold, and Frank’s wife’s hair was in the bed, and I lost a bobby pin in the bed, and I felt like my body was meat encased in a thin layer of television static, which a psychoanalyst would later close read as an image symbolizing disassociation.

After thrice having sex with Frank, I turned into a floating sheet. I felt uncomfortable with the negative emotions I experienced while succumbing to his flesh, not because I did not say no, but because I did not not say no. And in my not not saying no, I did not know how to not say no. So I said no, and was not heard, or I was heard but not listened to, and as a consequence, my self-esteem neither was nor wasn’t.

To speak the truth, Frank had power over me. He had a wife, and his wife could potentially learn about me. At night, while falling asleep, I would fantasize about her gaining access to my apartment. Maybe a neighbor returning home late would hold the front door open for her; or maybe she would show up in a rage and punch the front door’s glass with her fist, and open it, and ascend two flights of stairs. Maybe she would stand in front of my apartment, and knock three times, and I would foolishly answer without looking through the peephole, and there she would be—Frank’s wife, coming to strangle me. Because my self-esteem is such that I appreciate being choked, I let her wrap her hands around my neck, and as I stand outside of myself—once again, disassociation—I watch as my eyeballs bulge and my face turns red. “How dare you let Frank enter,” Frank’s wife would say. Yes, I think. I agree. How dare I?

Dare I say, I was foolish then. At that time, I thought I was a straight woman. But now I know: I am a gay man. As such, I no longer let straight men enter. Instead, I maintain close proximity to men who have no desire to touch me. Sometimes, it is painful—not because I want these men to touch me, but because there is no one in my life who touches me the way I deserve to be touched; that is, empathically, with knowledge of the fact that human beings are mere animals that need to pet and be pet, hence the expression heavy petting, which feels inappropriate in relation to the events I am doing my best to relay here, though I recognize memory is replete with caesuras, and that I am unable to articulate with utmost certainty what exactly happened that night. I made an unwise decision that carved out a space, and in that space, Frank did not think about my body at all, inserting as he did his ego into me: once, twice, three times. In not thinking about my body, he was also not thinking about his wife’s body, which is something she points out when she comes over to strangle me: “Now I have a sexually transmitted disease!” And I feel for her, I do. My parent has a sexually transmitted disease, too. When I was five years old, my father said: “I have HIV.”

The HIV was contracted during a trip my father took with a man named Dave—his name was Dave, as all men are Dave—a “friend” with whom he was “conducting scholarly research.” This trip took place in Florida, where my father and his friend stayed in a hotel with a balcony overlooking a bright blue pool. Do I remember learning how to swim? As my father spoke, I imagined his body slow dancing with his friend. It is night, and it is humid, and as I imagine my father’s pleasure, I try to channel how liberating it must have felt to experience—from the Latin experientia, from experiri ‘try’—another man’s flesh, as if his skin were meat or one step of the scientific method. I think of my father’s sexual encounter with Dave as a learning experience, and I wonder if this moment was filmed so it could be revisited over and over.

Two months ago, I dreamt that a gay man I do not know, with whom I share two mutual friends, was slow dancing with me in the middle of a cement room. The room was unrecognizable but felt familiar. When familiar yet displaced architectures appear in my dreams, I refer to these spaces as the [redacted]. As the gay man I do not know danced with me in the [redacted], I felt treasured, safe. He did not want to take off my pants. He did not place his fingers in my mouth. I knew he would not try to take my integrity away.

As we slow danced, no music played. Nor did I look into his eyes and tell him I loved him. I didn’t. Rather, I wanted to be him: to possess the ability to sleep with men like himself; men who, for the most part, feel safe, though I realize this generalization about the man’s experience of his culture is precisely that, and that my lack of firsthand experience as a gay man—beyond my DNA, my gay DNA—leaves me without evidence to the contrary.

The gay man I do not know places his hands around my waist, and holds them there. I close my eyes. I place my cheek on his shoulder. He places his head on mine. The encounter feels close, and in this closeness is contained an alien quality that brings us even closer. When someone or something is unlike you, you may push it away or get curious about it, violate its boundaries or transgress set expectations in relation to the way you are expected to relate to it. The transgression that takes place between us—myself and the gay man I do not know—is one of the heart. We experience a romantic yearning directed toward one another’s souls, the opposite feeling from death. This is also a feeling of gender reversal. For at some point in the dream—when I become bored with dancing, or when the man I do not know takes his head away from mine—I lean down, unzip his pants, and extract his ego from his pale blue boxer briefs. His ego is cold, grey, chafed. I look at it, then place my mouth on it. It does not budge; it does not command its y-axis. Rather, it continues to limply cascade between his legs, and I continue to kneel, trying to rescue it, but in this moment our closeness is dead, though I am very much alive, doomed to replay this encounter for quite some time.