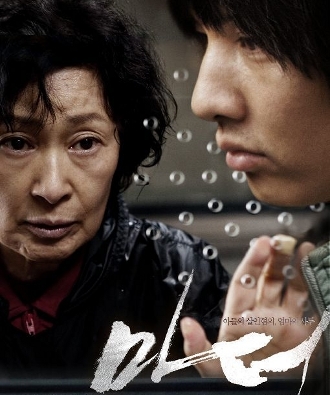

Bong Joon-ho’s Mother

07.04.10

Movies that open with dancing are typically Astaire-type affairs, Golden Age Hollywood projecting light-footed fantasies of itself onto the great screen of America, the sort of films whose greatest act of violence is the heroine half-heartedly slapping the rakish hero for his presumption. Not so with Mother, the latest offering from Korean director Bong Joon-ho, which begins with a Korean woman of late middle age sojourning across a prairie field, eventually stopping to waggle her arms at the sky in a hippie-dippie swoon, her facial expression morphing from horror to giddiness to unease to stupefied wonder. It is an apt and unsettling overture to a film that is an id-fest rather than a rhapsody, not Busby Berkeley but Alfred Hitchcock.

Movies that open with dancing are typically Astaire-type affairs, Golden Age Hollywood projecting light-footed fantasies of itself onto the great screen of America, the sort of films whose greatest act of violence is the heroine half-heartedly slapping the rakish hero for his presumption. Not so with Mother, the latest offering from Korean director Bong Joon-ho, which begins with a Korean woman of late middle age sojourning across a prairie field, eventually stopping to waggle her arms at the sky in a hippie-dippie swoon, her facial expression morphing from horror to giddiness to unease to stupefied wonder. It is an apt and unsettling overture to a film that is an id-fest rather than a rhapsody, not Busby Berkeley but Alfred Hitchcock.

Indeed if scene one is indebted to the unmoored emotion and dreamy physicality of Easy Rider, scene two is straight out of Rear Window. The dancing woman (played by the marvelous Hye-ja Kim) is now hunched over a cutting board in a dark shop, chopping just the sort of wild grasses she capered among minutes before. Following her gaze we look out through the shop’s door across a busy street to a pair of boys playing with a dog by the curb. The only sounds are the whiz of traffic and the slice-thomp of the butcher knife. The woman – unnamed throughout the film – watches nervously as one of the boys, her mentally disabled son, picks up the dog and waves its paw at her, the blade inching hack by hack closer to the hand holding the dried grasses. Then at the same moment, a car flies by, smashing one of the boys, and the knife crops off the tip of the woman’s finger. Yelling, she rushes across the street to the boy. He is dazed but seems mostly uninjured, nevertheless his mother panics at the sight of blood on his shirt, not realizing it’s her own.

Later, after a teenage girl is found dead, slung over the ledge on the roof of an abandoned building, Do-Joon, the woman’s sweet but useless son becomes a suspect. The police pick him up on the street, take him to the station, and coerce a confession. The bulk of the film is driven by his hardnosed mother as she tries to prove his innocence with the help of a few unlikely allies.

What follows is part police procedural and part thriller, with more than a little horror stitched in. The wunderkind director Bong gravitates toward genre – his last two efforts centered upon a serial killer and a river monster, respectively – and while Mother is a more mainline drama, the actions of its characters grow to seem serial, fatalistic, obsessive, and by its end, nearly everyone is revealed to be a monster.

Mother might be called a Korean Mystic River, and unlike many of the Asian films that make it across the Pacific to land in American theaters, its Eastern-ness is incidental: there are no samurai here, no ninjas, yakuza or geishas, no Ming emperors, kung-fu fighters, Buddhist monks or kamikazes. For this we should be grateful. Like Eastwood, Bong is a master of ratcheting tension click by click, and like Mystic River, Mother’s dénouement hinges upon a mistake, a revelation, and a shocking reaction. But Mystic River bristles with Eastwood’s cowboy masculinity, its most iconic image the tattooed back of a slab-muscled Sean Penn, whereas Mother follows the strivings of an older woman who is politically powerless, socially awkward, and gets things wrong more than she gets them right. All she has is her dogged love, as seen in Mother’s most iconic image, an arresting shot of Do-Joon urinating against a wall as his mother scuttles over to him and pours a cup of medicinal broth into his mouth. Like so many of the scenes between them, it is tender, grotesquely comic, and disturbing in its intimacy, and the film is summed up well in the tableau of a loving mother trying to pour healing into her damaged son while he pisses it away.

The film balances on the fine-grained performance of Hye-ja Kim, who is exceptional in the title role, and it is with unwavering intensity that her face and body are inhabited by a dark cycle of fear, solicitousness, lock-jawed grit and hysteria. The mother is an underdog, and in her frequently botched detective work there is none of the elegance of Hitchcock’s sleuths and spies. Not only is she an amateur – she’s not a particularly virtuous one, and perhaps her sole redeeming quality is her monomaniacal mother-love.

The film balances on the fine-grained performance of Hye-ja Kim, who is exceptional in the title role, and it is with unwavering intensity that her face and body are inhabited by a dark cycle of fear, solicitousness, lock-jawed grit and hysteria. The mother is an underdog, and in her frequently botched detective work there is none of the elegance of Hitchcock’s sleuths and spies. Not only is she an amateur – she’s not a particularly virtuous one, and perhaps her sole redeeming quality is her monomaniacal mother-love.

In fact, none of the film’s characters are admirable, and while Bong shares with Hitchcock an endless supply of cinematographic inventions and a love of minor-key strings, his characters belong to a different ethical universe. The summary of a movie about a mother trying to vindicate her falsely accused son might seem like a feel-good tearjerker, but the film is in fact a feel-bad cringe-inducer. Mother is unremittingly dark, a film without heroes, and the revelation of the truth brings no closure, no catharsis, only more pain.

It is no coincidence that the mother is an unlicensed acupuncturist, and she believes that her needles can alleviate any hurt, whether physical or psychological. In one of the film’s many blackly comic scenes, the mother, while visiting her son in jail, tries to convince him to press his thigh against the speaking hole in the Plexiglas so that she might insert a needle into his thigh and cure his terrifying mental confusion. The guard intervenes before she can, but at the end of the film, after a roller coaster’s worth of twists and turns, Bong returns us to that panacea in needle form. Sitting dejected on a train of vacationing mothers dancing to celebrate their temporary freedom from their children, she hikes up her skirt and performs self-acupuncture on the spot she described to her son. Immediately the despair in her face effervesces away and she stands in the aisle to join the loose-limbed ballet.

In the dance the movie ends where it begins, but after the preceding events, nothing could be more nauseating than jubilation. In a film that seemed solely shot at night in the rain, it should be a relief to see the sun glaring through the windows of the train, silhouetting the dancing women, but the sunshine seems false, as horrifyingly inappropriate as the dreamy grin on the good mother’s face.

_______________________________________________________________

Related Articles from The Fanzine:

Michael Busk on My Life with the Taliban