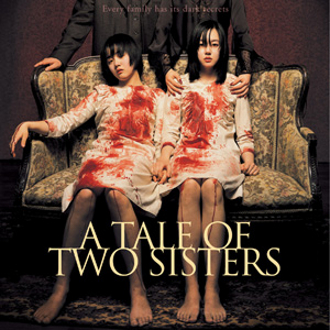

Kim Ji-woon’s Tale of Two Sisters

03.03.10

2004: Cul de sac in Minneapolis, February, four p.m., already dark, Craftsman-style bungalow, strangely narrow living room. I am reviewing a Tartan Asia Extreme video while the pale screen of my television illuminates my ghastly but gradual transition from young ‘n’ hip to old ‘n’ poor when the phone rings — my family, calling to wish me a happy forty-third birthday which is, oddly, on the same day as my mother’s. My mother, sisters and their kids are all in the Caribbean for a family celebration to which I could not afford the ticket. My husband/Registered Nurse politely takes a message and then endures my howling imprecations against my fate, family and fortune.

2004: Cul de sac in Minneapolis, February, four p.m., already dark, Craftsman-style bungalow, strangely narrow living room. I am reviewing a Tartan Asia Extreme video while the pale screen of my television illuminates my ghastly but gradual transition from young ‘n’ hip to old ‘n’ poor when the phone rings — my family, calling to wish me a happy forty-third birthday which is, oddly, on the same day as my mother’s. My mother, sisters and their kids are all in the Caribbean for a family celebration to which I could not afford the ticket. My husband/Registered Nurse politely takes a message and then endures my howling imprecations against my fate, family and fortune.

An eccentric scene, but not unheard of: in America people often sit in front of their TVs a thousand miles away from their “families of origin” and phone calls are second only to emails in terms of instant miscommunication. What happened to the notion of family, to honor and obligation? Modern “blended” families sometimes feel like a bunch of uneasy strangers moving around the world piece by piece, sending each other ambiguous messages of guilt or indifference, always ready to choose a new spouse or the next batch of kids. Everybody lives five thousand miles away from every one else. Here I am middle-aged, I moan, and my 70-year-old mother goes to more cocktail parties than I ever did. Who does my mother live near and whose mortgages does she pay? Her stepdaughters. While I, her real daughter, sit in cramped and darkened exile, worrying about the heating bill. Filial piety – promising to love and respect my mother – was never offered as an option and I’d be filial all right, if I wasn’t so stressed out about money all the time, etc. in a stream of self-pity.

Calm down. My husband soothes his way into my monologue, Watch this film. It’s about a family with some real problems. He titrates the methadone/chocolate milk/ I.V. drip to which I am permanently attached and slips in Korean director Kim Ju Won’s Tale of Two Sisters. Two hours later, I call my mother to beg forgiveness.

Tale of Two Sisters may not affect everyone like this but it’s based on a fairy tale, and fairy tales often communicate universally. The Korean folktale “Rose Flower, Red Lotus,” the source of film, is grimmer than a lot of modern day horror flicks. At one point, a boy is instructed by his mother to place a crushed rat in a sleeping girl’s bed, intended as an impostor aborted fetus to impugn the girl’s chastity. The stepmother in the story makes Snow White’s seem like a doting icon of maternity. In Kim’s 2003 film adaptation, he jettisons the rat, delivering instead a young girl gnawed by another kind of beast. The film’s short prologue consists of a shot of a young girl’s face as she’s asked–by an unseen male authority figure– “Who are You?” The rest of the film constitutes her tragic answer.

In the film’s opening, Su-mi (“Rose” in the original story) and her sister Su-yeon (“Lotus”) arrive home to a large, gated house in the woods. They emerge from a black car, two girls on the cusp of adolescence, dressed in child-like clothes. Rose is all in red, reminding western audiences of Riding Hood, and there is something fierce and self-contained about the way she links hands with her soft, pale sister. “I’ll protect you,” she later swears to her as they lie on a floating dock at a pond, surrounded by the cluttered, clasping trees. Afterwards they enter the family home and stepmother Eun-joo, emerges from shadow like a pale moon, all tight smile and bright, brittle chatter. Played by actress Jeong-ah Yeom, she’s so razor-thin her collarbone should get it’s own screen credit, and she seems as haunted as the darkness surrounding her.

Darkness in fact, is the first and foremost element in this family home. The only thing filmed in light are the two girls, and the contrast is instantly unnerving. The air crackles with barely supressed rage and free-floating anxiety. Su-mi is the one coming home from the mental hospital but it’s stepmom who takes the pills for melancholy that her deflated husband provides. When she tries to slip in bed with him, he wordlessly retires to the couch. Later, her show-stopping meltdown at a dinner party at first seems inexplicable until, as we understand more, her actions make shocking, subconscious sense.

Darkness in fact, is the first and foremost element in this family home. The only thing filmed in light are the two girls, and the contrast is instantly unnerving. The air crackles with barely supressed rage and free-floating anxiety. Su-mi is the one coming home from the mental hospital but it’s stepmom who takes the pills for melancholy that her deflated husband provides. When she tries to slip in bed with him, he wordlessly retires to the couch. Later her show-stopping meltdown at a dinner party at first seems inexplicable until further down the line her actions in retrospect make shocking, subconscious sense.

Su-mi insists that her stepmother is abusing Su-yeon, who is as endearing and slow as a puppy with a head injury. With a paroxically ethereal clumsiness, she trundles beyond the “shy Asian daughter” stereotype into a kind of infantile sweetness: You would have to be some kind of puppy-kicking monster to imagine being cruel to her. Stepmother Eun-joo is indeed frightening; high-strung, liable to spit out bitter, nihilistic truisms. Su-mi, however, is the one that we watch kills a small, helpless animal.

The set design also puts the audience on immediate alert. Working closely with art director, Geun-hyeon Jo, Kim built an actual house to be used as the set, full of sharp-angled shadows, tastefully hectic. In any movie where a family is menaced the house is important: in American films it’s usually an expensive example of disconcerting modernism, to signal that it is at once dream home and nightmare. Kim’s set goes further, the house becomes the woods these babes are lost in. Using William Morris patterns, Geun wallpapers each room with it’s own dense, febrile vine-and-flower motif. It’s the same hysteria-inducing Victorian rococo that drove the heroine in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s feminist classic The Yellow Wallpaper straight into the thickets of her subconscious. Fittingly for the feminine characters and set of concerns for both works, the term ‘hysteria’ derives from the Greek for womb. More Freud than Frankenstein, one of the first signs something’s amiss in this house is that all three women get their period at once. In an appropriate contrast, the house is also quite beautiful: an ideal of feminine innocence and privacy, the poetic architecture and interior design somehow mutilated, soft shadows turning into plain darkness — a haunting house.

So what is the secret wound that is infecting this home? The death of girls’ biological mother? It’s got to be something worse: there are evil eyes looking out from under the sink and they aren’t the eyes of anyone’s mother. The father looks bewildered and broken and the duel between Su-mi and her stepmother seems to be played for something much larger than this man’s affection. When the story is finally told this family isn’t “mended,” nor is “the monster” punished. As the plot is revealed in these rooms that were intended to be beautiful, sadness, as much as fear, makes itself at home.

Tale of Two Sisters is a good fright-flick, full of the required unease, mystery and dislocation, but what is it about the movie that would make someone want to call their family? The score, for one, flows out of fright and into sorrow. When horrible things happen, the music mourns without a saccharine note or else falls silent, as if abashed. In the end, this is a film that’s strong enough to rip the pettiness and self-injury out of my supremely individualistic head. It leaves you with a longing for grace along with a pleasing sense of dread. You won’t ever forget the movie’s last shot: a young girl’s angry face looking back at the home she doesn’t yet know is destroyed. Angry words, once spoken, the film suggests, can never be unsaid. What Su-mi has said to her stepmother is basically this: “I hate to be near you, I’m happiest when I am as far away from you as possible.” It’s tame by American standards, where daily you can hear 15-year-old girls telling their mothers: “Shut up and die, you psychotic cunt, and it’s $285 for the pull-ons, not the fucking boot-cut.” Somehow, though Su-mi’s words are much more final. It reminds a Western viewer that we do, in our families, often live as far away from one another as possible. This film suggests there’s horror in distance. Elders should be honored and honorable, and when they’re not, darkness enters through the gap. In an imperfect world, full of imperfect families, the film reminds, forgiveness is all we have to keep our house from becoming a forest at night.

So call Mom. She misses you.

______________________________________________________________

Related Articles from The Fanzine: