Body Horror: Eating disorders, anatomy, and place (2)

06.04.17

[This part two of this essay; for the first part, begin here.]

And so from Galen to Vesalius, from Vesalius to Doctor Frankenstein, we come to The Fly. It is in Frankenstein that the doctor refers to the monster as ‘devil’ and, fittingly, ‘vile insect.’ I remember watching The Fly and thinking that this was my teen movie. My friends watched American Pie 2 and there was me, alone, watching The Fly in my bedroom. I was 14 years old when a friend of mine had a birthday party and didn’t invite me. I was not good to be around. Having lost a lot of weight, my anger levels increased. I started fights on people. I wanted to hurt people. I hurt myself too. And I remember seeing a group of guys from my year and they went quiet. I knew I wasn’t invited, but I stuck around for a bit anyway. I made jokes about my own body. I ripped into myself with words. My friends laughed, but there was still no invite. I think perhaps I was angling for an invite, but I knew it wouldn’t come. I was damaged goods. It was I who felt I was the vile insect.

Going back to my bedroom at home, I shut the door and took in the images of The Fly. As Seth starts to transform, he becomes more physically and sexually aggressive. We shared some of these traits, I felt. I was certainly an angry young man, starting fights on people and raging at inanimate objects. But it was with Seth’s secretions that I saw a mirror to my own body. When Seth begins to fully transform into a fly, he begins to vomit up liquids. His body is rejecting the human version of himself: a body at war with itself.

The Fly (1986)

When I ate food at the dinner table I would put the food in my pocket, even though I knew my parents could see everything. I even packed my cheeks full with chewed up food and kept it there like a gerbil, asking if I could go the toilet. I would run upstairs to the bathroom and in the boiler cupboard, there was a hole in the floor. It was here that I buried my food, threw it down the pit as it were. The chewed-up food that I chucked away had the same consistency of the fly. It felt as if my body was rejecting who I wanted to be. Food was, and still is for me, an object of desire. It’s what I wanted, but couldn’t have. Again, I wasn’t living out the teen movie like my friends thought they were: my body was going through a transformation. In my mind, my body was a horror film, frustrated, manacled.

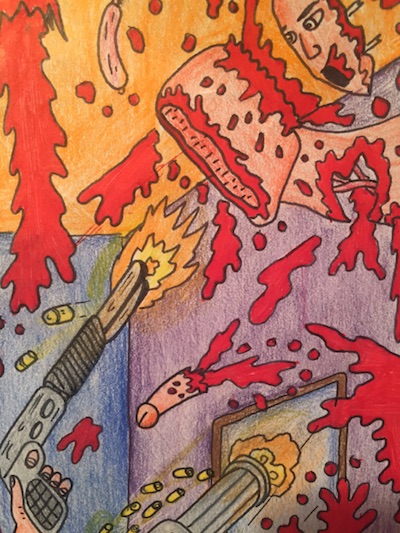

This is when my own drawings began. Looking back on these drawings now, they are juvenile and ridiculous, badly drawn and crude. Usually there is a male figure in the centre of the picture who is decapitating various people with axes, chainsaws and swords and mostly everybody had bald heads. There is nothing to be read into this, other than the fact that bald people are easier to draw. But perhaps there is something to be read into the amount of genitals that are flying around, the amount of blood and guts and gore that fills the images.

Here we can see a head being shotgunned so hard that a brain has flown out the roof of the head, high above the disco floor. Just next to this unfortunate soul is a man whose head has inexplicably exploded with a fountain of blood. His arms, too, have come off and are pouring with blood too.

The pièce de résistance is, of course, the penis that has pierced the man’s temples, going in one end and out the other, taking out an eye in the process. Subtlety did not figure here. This was a world in my head of Braindead proportions. Body parts fly across the floor, blood gushes out of orifices like water and guts are spilled. Faces are literally blown out the back of heads; random sausages fly across the room along with bullet casings and cocks.

This overabundance of body parts is linked to the idea of eating. The fact I could not digest a story from start to finish, that I had to constantly pause and rewind, that I saw films and books in fragments, is partly remedied in these images. I felt the need to put everything on one page. I could have drawn one thing beautifully, but I chose not to. There needed to be a feeling of suffocation on the page, a feeling that the flying cock and vaginas and breasts and heads were absolutely necessary.

I think of Peter Jackson’s Braindead again, a film so over the top, so utterly drenched in blood and guts and gore that it is truly a feast for the eyes. Perhaps that was it, then: in drawing my own gory feasts, I provided my own nutrients that were so lacking in my diet. My diet was taken through the eyes. I ate bodies through them and became a glutton for gore. I saw bodies and blood as a banquet.

The drawings, for all their excess, kept me sane. My obsession with anatomical drawings and medical illustrations from old pathology books kept me alive, in a way. And this all derived from the moving image. For me, I remember looking at myself in the mirror, naked, and seeing a monster. But when I watched those movies, I saw a world where I could indulge in gory fantasy. And now, with the benefit of hindsight, I saw a world where things could transform again. I felt like a monster at 14 years old, but maybe, I thought, there was a light at the end of the tunnel and that these drawings were a kind of restorative.

Place

This isn’t a hotel, it’s a nuthouse!

Basketcase (1982)

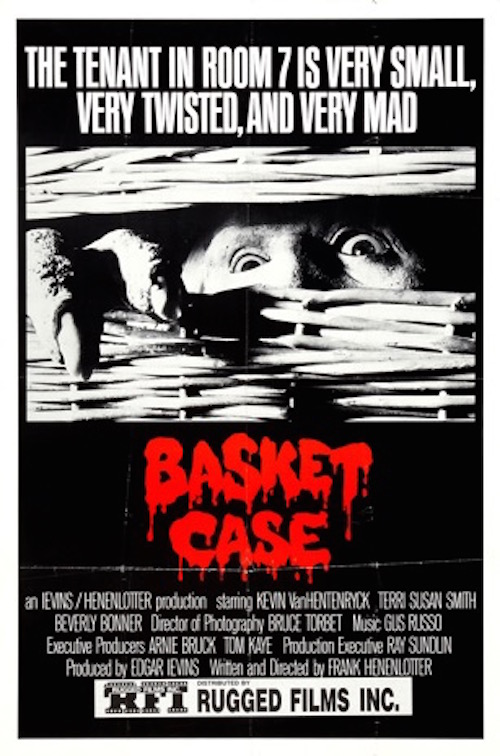

I was first drawn to Frank Henenlotter’s Basketcase because of its poster. The title is written in red blood, set against a black background. The face of the Belial, the monster, is peeking out of the basket with his sharp-nailed fingers creeping out. And then there’s the tagline: The tenant in room 7 is very small, very twisted and very mad.

Made on a shoestring budget, Basketcase is the story of Duane Bradley and the terrible secret he carries around in his basket – his Siamese twin, Belial. After surgery to remove them, Belial is deformed. He wants to hurt everybody he comes into contact with, whilst his brother wants to live a normal life. The cast and crew was so small that the end credits are mostly made-up names so they didn’t have to repeat names over and over.

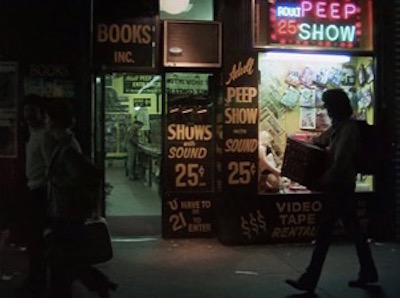

More than anything, I think it is the locations that stay in my mind. Henenlotter is like a grindhouse Scorsese here and in Basketcase, the locations feel like they could have been used in Taxi Driver. There’s the Hellfire Club and Franklin Street and Hubert Street. Tribeca. Duane Bradley walks with his basket through the seedy streets of New York City, past peepshows and adult theatres.

This was a New York of welfare hotels like The Martinique. Built in 1897, its guests all shared something in common: wealth. It was in the 1970s that the decline began. The city started renting rooms as emergency housing for the homeless and it was then that the hotel assumed the identity most New Yorkers know it for – ‘as the most notorious of several crime-infested depositories of poor people known until the end of the 1980’s as welfare hotels.’

In the New York Times, Sara Rimer writes that for one family ‘though the walls of the city-owned Harlem tenement are crumbling, rats roam the courtyard and strangers smoke crack in the hallway, Ms. Bosket says it is a vast improvement over their last residence – one room at the Martinique Hotel.’ Rimer interviews a woman from the Dominican Republic:

In her two rooms at the Martinique, she and her children at first sat on the beds when they ate.

”I found a piece of wood in the garbage and put it on top of a barrel for a table,” she said. ”Then I found two chairs in the garbage. One of the workmen got me two more chairs. Then one of the managers gave me a chair, so we had five chairs. Eventually we had seven chairs. It took me almost nine months.”

This is the world of Basketcase, a film that’s not only concerned with the grotesque body of Belial, but also with the social body of Manhattan. The true horror of Basketcase is New York itself, a city in desperate need of its own surgery, a place that Robert Hayes, director of the coalition for the Homeless, said was a place of ‘grinding, abject poverty.’

It is this world that Taxi Driver takes place in too. Although Martin Scorsese’s film doesn’t strictly fall into the same genre as Basketcase or The Fly, it is very much one that is concerned with bodies and transformations. Scorsese remarked that the film was like a mix between the ‘New York Daily News and a gothic horror.’

Scorsese himself even noted that the atmosphere in the film, especially in the night time scenes, are ‘like a seeping kind of virus.’ He goes on to say:

When you live in a city, there’s a constant sense that the buildings are getting old, things are breaking down, the bridges and the subway need repairing. At the same time society is in a state of decay.[1]

The dark hallways and seedy neon peepshow signs of Basketcase are apparent in Scorsese’s New York too, a city in a state of decay. Travis Bickle rides his taxi, picking up customers, cleaning the ‘blood and cum’ off the back seats and then repeats the shift again the next day. Day and night become one. He is god’s lonely man.

But the idea of routine and transformation is what interests me most about Travis. The dedication to his routine. Training and isolation. Push ups and pull ups. Drawing the gun in front of a mirror. Repeatedly pulling the knife from his boot. This is Travis. Routine to the point of religious ritual.

In Travis’s last act of violence, he enters the brothel where the young prostitute, Iris (Jodie Foster) plies her trade, and shoots everybody. Travis couldn’t watch any longer. But focus on the bodies. The fingers exploding from a man’s hand. Blood leaking from a neck. Bullets tearing holes into a cheap suit. A gun pushed up to a cheek, blowing brains out all over the wall. Travis and his wet, bloody finger.

The last act of violence as an act of catharsis. An orgasm.

And so returning to the pictures I drew as a teenager, perhaps this was my catharsis. These drawings were my way of articulating the war inside my own head, the war I waged on my own body. And those feelings of anger and loneliness and desperation have been put away like Belial, in a basket of my own making, but they are still there lurking, their fingers creeping out occasionally.

—————-

[1] Scorsese on Scorsese, ed. David Thompson and Ian Christie.