Body Horror: Eating disorders, anatomy, and place (1)

05.04.17

Body Building

Tawny: Are you a body builder, or something?

Seth Brundle: Yeah, I build bodies. I take them apart, and put them back together again.

– The Fly (1986)

When I was thirteen, I remember inviting my friend Daniel over to watch Day of the Dead. I haven’t spoken to Daniel in a long time and I would be lying if I said that the watching of that horror film marked the end of the relationship, but it certainly set a marker in my teenage years in regards to the person I was and would turn out to be.

You could say what we fell out over was a difference in our bodies. I mean this in the most literal way possible as well as mentally. I can’t remember now why I invited this friend to my house seeing as he had humiliated me at his birthday party a few months earlier. The morning after his party, Daniel’s mother cooked breakfast for us all. Daniel and his other friends –I barely knew them – were eating at the table. All except me. I used my fork to push the food around the plate, to strategically make room to give the semblance that I had eaten something when I really hadn’t. I remember everybody looking at me out the corner of their eyes like I was a freak or some kind of monster. I had been struggling for nearly a year with an eating disorder that would dominate my teenage years and, at thirteen, still didn’t understand what was happening to my body. I was frustrated that I couldn’t put solid food in my mouth. It was like a mental block. I would routinely punish myself for my behaviour. I was like a religious penitent, punching walls with such force that my knuckles would bleed, smacking my head against brick walls like Jake La Motta. And so when Daniel took me aside, he told me how embarrassing my behaviour was. Why can’t you just be like everybody else, he said. I didn’t have an answer. I never did back when I was thirteen, usually choosing to look down in humiliation and scream inside my own head at my failure to control my body and mind.

And then, months later, Daniel agreed to come over and watch Day of the Dead with me. I think I know why he accepted my invitation. It was an embarrassment of his own, like I had a secret of his and he didn’t want me to reveal it. At that same birthday party, we went to hang out behind some council flats. Daniel and two of his other friends pulled their pants down and started to compare their penises. I didn’t join in. My friend Daniel was upset because his was the smallest and the nerdiest guy, Edward, had the largest. I didn’t care, but I was thinking, even then, that we are all at war with our bodies. That we measure ourselves up to other people and look at ourselves in mirrors.

Sometimes at school, before the days of iPhones, we would print off pornography from the internet and look at it together in the dark corners of the school. The printer never printed the images fully because the ink ran out easily or sometimes the paper had been ripped in two. There we were, teenage boys in 2001, looking at fragments of bodies. We became aroused at half a leg or a pair of breasts. Deeper in our mind still, we were turned on by collarbones and veined feet, anuses and testicles. We masturbated to amputated pictures of bodies but not just that. We did it to the bodies in our mind, the bodies that shapeshifted in the dark of our mental landscape. Women grew taller and lost limbs in there or, like one of Wim Wenders’ photographs, there were bodies seen through the frame of a carpark, obscured.

Wim Wenders

Even Daniel, who had shouted at me for not being able to eat, who had told me off for not fitting the mould of what a friend should be, was ashamed of his body. When we all went back to his house, he used a ruler to measure his penis and asked me to do the same. I didn’t.

So when he came round to watch Day of the Dead, there was a silence between us. Was I going to betray him and tell everybody what had happened behind those council flats? I wasn’t, though I see the irony in writing about it now. But I write about it now in order to understand something. It was when I pressed play that I realised I didn’t have the capacity to digest narrative. In the same way that I couldn’t consume solid food – I stuck to chocolate mousses and tomato soups at 4pm and 10pm every day, sometimes sucking the salt off crisps – I found myself unable to cope with watching a film from start to finish. I would hate myself for this and sometimes cut myself to punish myself.

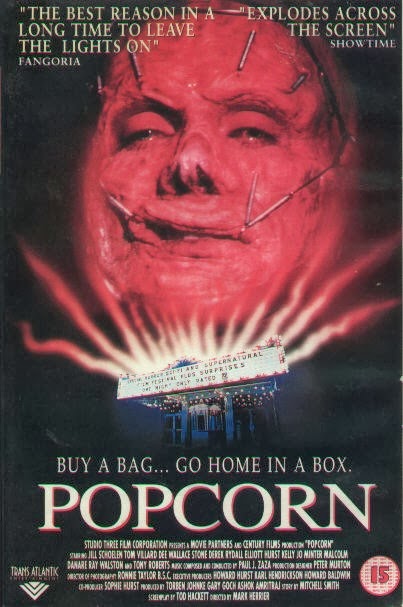

The films I gravitated towards were horror films, films like Dawn and Day of the Dead, Zombie Flesh Eaters, Basketcase, The Fly, Alien, The Thing, Society, Reanimator and Hellraiser. These films were perfect because I could stop and rewind scenes of torture and gore. Sometimes I became obsessed with just the VHS covers like Popcorn (1991), something I saw at the video shop around the corner from my house at the age of four or five. I was exposed to bodies at a young age, whether they were in my mother’s pathology books or on VHS covers, burnt and spiked. This was a childhood of eating things through my eyes.

I even made lists of my favourite scenes from these films. The splinter in the eye from Zombie Flesh Eaters. The sound the man makes in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre as Leatherface hammers his head in. The pencil in the ankle from The Evil Dead.

But as a thirteen-year-old boy, I never questioned why I did this. It’s only now, thinking about that time when Daniel came over, that I realised there might be another reason for my obsession with these films. As Daniel sat there at the foot of my bed, I rewound and played, rewound and played, rewound and played the grisly death of Rhodes in Day of the Dead.

Day of the Dead

I watched with glee as he was ripped in two, his guts pulled out, his heart, liver, stomach and bones chewed on by the living dead. Daniel said nothing. He didn’t need to be there; I was playing this VHS for my own self-gratification. He said he didn’t like films like this. I just replayed the tape until he left.

This replaying of Rhodes’ death was more than just a teenage boy being obsessed with gory movies. Perhaps, instead, this replaying of a man being ripped in two was my version of a cry for help. I didn’t understand my body and here I was watching a man being rent in two, his own insides being distributed and eaten by zombies. The screen body being taken apart was like a table of contents to me, like a book to be read. I couldn’t digest the entire film, so here I was with scenes and moments, deaths and dismemberments, watching bodies “being taken apart” and, in my own head, taking myself apart and hoping, like Seth Brundle, I could put it back together again.

However, these films influenced me in ways I have, until now, forgotten about. It’s 2016 now and I still find moments of those teenage years coming back to me, whether that is through nightmares or conversations with my parents. But upon returning home this Christmas period, I found some papers tucked away in a cupboard, papers that when I look back on them now show the disturbed mind of a young boy, but one trying to piece himself together again through body parts and gore, to restore himself through film and books and anatomical drawings.

Drawings

Humans have always been interested with what’s inside their bodies and the potential of transformation.

With Galen, our understanding of anatomy was derived mostly from animal cadavers, notably due to the lack of human ones available. There were questions of how we work and why we don’t work: there was only so much an animal could teach us. Many believe that Mondino de Luzzi, a 14th century anatomist from Bologna, was the first person to produce an anatomical text of note, but there are many who dispute this, stating that he didn’t know the body through practical experience but through bodies of text, through translations of Arabic and Greek work. There was Leonardo Da Vinci, who after abandoning the anatomical teachings of Galen, decided to rely on his own gaze: after dissecting around 30 human bodies, Pope Leo X ordered him to stop. But what was left were beautiful drawings of the human anatomy.

And then there was Andreas Vesalius. What interested me most about Vesalius were the drawings. Skulls and skeletons, men with their skin removed exposing their muscles, their heads facing heavenwards just like Jesus Christ. One page shows the palms exposed, opened up and the veins reaching towards the ground, which as an image, is echoed centuries later in A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors, when one of the young patients is dragged by their veins like a puppet by Freddy Kruger.

A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors

Illustration from Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica

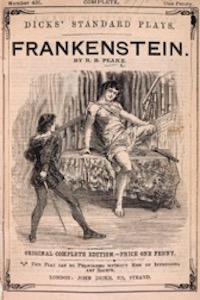

In order to draw the body and explore its interior, there was a demand for corpses. Bodies were stolen, graves robbed. In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, a work I knew as a butchered text in the first place having read the 1831 version and then the 1818 version, sees a man build a body from corpses. The descriptions of the monster are particularly interesting, reading like an anatomical study with ‘limbs in proportion’ and ‘his yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath.’ The hair is said to be ‘lustrous’ whereas the eyes are ‘watery,’ the same colour as the ‘dun white sockets in which they are set.’ The monster is a body of contradictions, at once showing signs of life and death. It is a body that is created as a tabula rasa, a body born innocent; it is through experience that the monster is corrupted.

The story went through numerous changes and transformations, from novel to play and from play to the silver screen in 1931.

With James Whales’ adaptation, we had the monstrous body moving, a black and white image flickering in the darkness of the theatre. Years later, I thought, this black and white image would soon be the glow of the cathode ray tube television, me and all my VHS’s, recorded off television, butchered by ad breaks. I saw the VHS as a body too, then, one that was a bastard of the original, a stitched together and edited version of what once was. But I loved the VHS tape and its raw quality, the sound of the tape rewinding almost sexual. Even pausing a video tape is sexual to me, the image distorted, the sound of the VHS player whirring.

——–

Check back for part two of this essay at FZ tomorrow.