Beyond Beyond Bedlam

20.02.12

It’s February in Zurich and everyone’s toasting the Lusitania and Pier 54. Everyone but me––I am wringing my hands on account of this Most Dangerous Method movie, which has vastly depreciated my stock of cocktail Jung and Freud closers. Whereas six months ago I could send some Freely-Discoursing Expert at the local into a fugue with a carefully timed “Did you consider that in ‘The Uncanny’ Freud claimed exactly this sort-of-thing was caused by the unexplained recurrence of the familiar” now even odds some wiseacre lobs back “Yes, but didn’t Jung disagree?” I’ll be on the wrong end of the Sunday morning arts & crafts hour at the Altersheim before there’s any money in psychoanalysis again.

It’s February in Zurich and everyone’s toasting the Lusitania and Pier 54. Everyone but me––I am wringing my hands on account of this Most Dangerous Method movie, which has vastly depreciated my stock of cocktail Jung and Freud closers. Whereas six months ago I could send some Freely-Discoursing Expert at the local into a fugue with a carefully timed “Did you consider that in ‘The Uncanny’ Freud claimed exactly this sort-of-thing was caused by the unexplained recurrence of the familiar” now even odds some wiseacre lobs back “Yes, but didn’t Jung disagree?” I’ll be on the wrong end of the Sunday morning arts & crafts hour at the Altersheim before there’s any money in psychoanalysis again.

So me and two pals each manage investment funds. Buddy 1 went bonkers over 4% Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railway Company mortgage gold bonds per 1 April 1934. Buddy 2 sold Buddy 1 default insurance in the remote unlikelihood of the unthinkable, neither of them having noticed the maturity date on these venerable documents. Buddy 2 bought land in the states with his investment trust, money so sitting on the table I sold him cover on the cheap. Buddy 3, namely me, my own operation was troubled out the gate. Sniffing a quick buck in technology I went big to attract a better class of investor. My colleagues rented pricey mailboxes on Paradeplatz––Zurich’s own Pennsylvania Avenue, an address which punches above its weight and price but down a block from the White House and up a floor you find night schools and thin halls where every door has at least five or six names painted on the glass. My enterprise however met an exclusion to the permit required for foreigners to buy land in the canton; I bought a briar patch down on the Pfnüselküste and took bids to build a big modern-looking thing, six stories of brick and stone with a columned façade, marbled, high ceilings, a richly decorated interior and a reverential hush upon entering like that at Napoleon’s Tomb. Over the months as I watched it being built I kept imagining that silence. Being no fool I bought insurance from Buddy 1.

A Danish construction enterprise won the bid for the building; terms of the contract translated into Danish by a reputable local translation agency (“Translation Agency One”) stipulated walls painted in graphite color (in Danish, “grafit”). Here the troubles began, for the translator turned it into “graffiti-painted walls” (in Danish, “grafitti”). So instead of watching the summer suns sink each night behind the Gold Coast, the day to cut the ribbon comes and I walk in lo and behold! believing jackals have defiled my temple pull a Fred Sanford.

On the horizon appeared legal consequences: to wit one lawsuit between my fund, the construction company, and Translation Agency One. As was determined only much later on appeal, during trial the translator from the second translation agency (“Translation Agency Two”), which I had hired for the express purpose of demonstrating to the jury the gaffe of Translation Agency One, this second translator translated the Danish back into English and, as she later testified, inadvertently corrected her own translation to conform to the first translator’s translation. At some point during review this second translator forgot that mistranslation was the essence of the dispute; in some sort of what a leading local psychiatrist referred to during his testimony in a much later proceeding as a “superego override” she “hyper-corrected” her own translation in order not to mistranslate the first contract. With the result that the two documents submitted to the jury, the contract 1) as it was and 2) as it should have been were identical––it appeared as if I were suing to have my walls covered in graffiti. Which is of course exactly what had already occurred. Given this substantial error of this mistranslation at the trial phase of the litigation the jury at the Bezirksgebäude quite correctly returned after 5 minutes with a verdict for the construction company. The trial was as lost as Walter Benjamin’s briefcase.

On the horizon appeared legal consequences: to wit one lawsuit between my fund, the construction company, and Translation Agency One. As was determined only much later on appeal, during trial the translator from the second translation agency (“Translation Agency Two”), which I had hired for the express purpose of demonstrating to the jury the gaffe of Translation Agency One, this second translator translated the Danish back into English and, as she later testified, inadvertently corrected her own translation to conform to the first translator’s translation. At some point during review this second translator forgot that mistranslation was the essence of the dispute; in some sort of what a leading local psychiatrist referred to during his testimony in a much later proceeding as a “superego override” she “hyper-corrected” her own translation in order not to mistranslate the first contract. With the result that the two documents submitted to the jury, the contract 1) as it was and 2) as it should have been were identical––it appeared as if I were suing to have my walls covered in graffiti. Which is of course exactly what had already occurred. Given this substantial error of this mistranslation at the trial phase of the litigation the jury at the Bezirksgebäude quite correctly returned after 5 minutes with a verdict for the construction company. The trial was as lost as Walter Benjamin’s briefcase.

The foreman read the jury’s verdict. The gavel rang like a shot, which I found discomfiting. There I was a British general in a Sepoy swirl, righteous injustice smote me like a thousand lynchings borne by steam locomotive cloaked in a cape. A cheer in the back of the courtroom swelled to a roar; I awoke within Burghölzli, as I was informed by my new roommate, in order to get my head fixed.

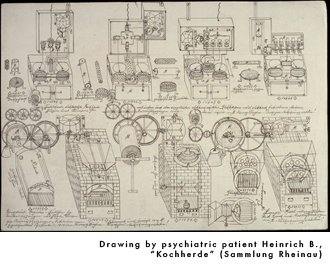

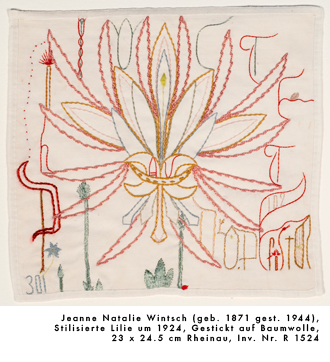

“The daily routine in the Rheinau Asylum was for the doctors and the patients determined by one thing only,––work! […] ‘[I]dleness is the patient’s worst enemy,––and work itself is the most decent tranquilizer.’” Iris Blum, Im täglichen Gange der Anstalt, Das Praxisfeld Arbeit in der Pflegeanstalt Rheinau in den Jahren 1870-1930. Do not believe these dates. The Medical History Museum at the University of Zurich recently concluded a show of art produced by inmates of the former monastery turned psychiatric nursing home in 1867 until its closure in 2000. The exhibit included several works of calligraphy and poems by Hermann M. (confined 1918 to 1943), a handful of designs for air and ocean vessels, hydro-electric cooking stoves and other mechanical fancies culled out of the two thousand patent applications left behind by former Swiss National Railway guard Heinrich B. (confined 1914 to 1926), and embroidering by Jeanne Natalie Wintsch (confined 1922 to 1925), who was included in the 54th Venice Biennial, an ambassador from the wacky world Outsider Art. Committed to Burghölzli in 1922 for violent behavior and religious delusions, she tried to escape and was taken to the incurable ward at Rheinau. There she took up embroidery.

Compared to the textual density in the other inmates’ works that often resembles Robert “clairvoyant of the small” Walser’s microscript, Wintsch’s works are colorful, buxom affairs, at first blush light on crazy. It takes concentration to recognize her meandering lines as distorted letters and then a good deal of patience to collect the letters into Old Testament names: Ararat, Jehova, Isis, etc. A friend had bad luck during Mardi Gras and wound up in Orleans Parish Prison (pre-Katrina), even by American standards a gladiator school. When asked how he made it out he nonchalantly replied, walking around screaming Biblical names. Nobody, it seems, wants to mess with a prophet. Wintsch apparently followed this strategy; her doctor, Oskar E. Pfister, son of Zurich theologian and psychiatrist Oskar Pfister (of the eponymous annual award given to contributors in the field of religion and psychiatry by the American Psychiatric Association) had her reclassified from incurable to cured––released after three years.

Compared to the textual density in the other inmates’ works that often resembles Robert “clairvoyant of the small” Walser’s microscript, Wintsch’s works are colorful, buxom affairs, at first blush light on crazy. It takes concentration to recognize her meandering lines as distorted letters and then a good deal of patience to collect the letters into Old Testament names: Ararat, Jehova, Isis, etc. A friend had bad luck during Mardi Gras and wound up in Orleans Parish Prison (pre-Katrina), even by American standards a gladiator school. When asked how he made it out he nonchalantly replied, walking around screaming Biblical names. Nobody, it seems, wants to mess with a prophet. Wintsch apparently followed this strategy; her doctor, Oskar E. Pfister, son of Zurich theologian and psychiatrist Oskar Pfister (of the eponymous annual award given to contributors in the field of religion and psychiatry by the American Psychiatric Association) had her reclassified from incurable to cured––released after three years.

I have heard it stated that the test for Outsider Art is whether the maker intended to create art––if not, then Outsider. Taxonomy has never been my strength; where I’m from intent is an issue for a jury to decide. But I have noticed that trench art, especially those brass shell casings beaten into obsessively detailed vases, has for the most part been forced to pitch its tent outside the castle walls of Outsider Art, a Bonus Army bivouacked on the wrong side of the Potomac. But there the analogy ends, unless Insider Art be New York but a New York that looked down upon the occasionally entertaining antics of its unwashed, slower southern neighbor. Lest I digress, I have heard this––I also have it on confidence that the purchase of Outsider Art is a ticket to the mythic past, a connection to a mystical world. Then again I was once harangued that Skid Row, a twenty block open air Andersonville where some 17,000 camp in downtown Los Angeles, was blood on the hands of Reagan, human detritus testament to his meanness towards the poor. In fact, it was unintended blowback from a 1972 federal court decision issued by Frank Johnson, probably the most compassionate civil and human rights advocating rump that’s ever parked itself on the federal bench. Johnson just as well-meaningly as one could imagine decided that the mentally ill have a constitutional right to treatment––and with the crack of his gavel a thousand hospitals closed, unsure but surely unable to afford whatever in the looming tsunami of litigation the Constitution would be determined to require. Thrown out on the street most inmates wound up reinstitutionalized through the state-financed criminal justice system. True story.

I make no secret my aversion to nuts and outright allergy to the nuthouse. I refrained from the activities indulged in by the others; I was there to be crazy, not make art. But as I watched between the bars as Wintsch waltzed out one foot on the sidewalk and one in the street I knew that if I were ever to make it over the fence I must don––the black beret.