The Cinema of Whitney Houston (with Bradford Nordeen)

23.02.12

“The Cinema of Whitney Houston” was written back in 2008 for a forthcoming collection of writings on cinema by Kevin Killian. Penned when Whitney was promising to release the first studio album since her 2003 Christmas record, the resulting album, I Look To You, both proved an adequate comeback record and cemented our fears that all was not right, nor was it okay. Though it debuted at the top of the charts, her public appearances––from Oprah’s couch to Good Morning America‘s stage––found our Whitney winded and lacking in the voice which once drove her fame. Ironically, Kevin and I were recently collaborating on new projects one afternoon, THE afternoon it turns out, February 10th, when Whitney was found in her Beverly Hills Hotel room, dead at the age of 48. We shivered at the happenstance that found us together again on this heartbreaking day and felt it was time to bring light to this piece, in advance of Kevin’s book and what will be Houston’s final screen performance, in Sparkle, singing "His Eye On The Sparrow," the spiritual most famously incanted by the great Ethel Waters in Fred Zinnemann’s The Member of the Wedding (1952). -Bradford Nordeen

“The Cinema of Whitney Houston” was written back in 2008 for a forthcoming collection of writings on cinema by Kevin Killian. Penned when Whitney was promising to release the first studio album since her 2003 Christmas record, the resulting album, I Look To You, both proved an adequate comeback record and cemented our fears that all was not right, nor was it okay. Though it debuted at the top of the charts, her public appearances––from Oprah’s couch to Good Morning America‘s stage––found our Whitney winded and lacking in the voice which once drove her fame. Ironically, Kevin and I were recently collaborating on new projects one afternoon, THE afternoon it turns out, February 10th, when Whitney was found in her Beverly Hills Hotel room, dead at the age of 48. We shivered at the happenstance that found us together again on this heartbreaking day and felt it was time to bring light to this piece, in advance of Kevin’s book and what will be Houston’s final screen performance, in Sparkle, singing "His Eye On The Sparrow," the spiritual most famously incanted by the great Ethel Waters in Fred Zinnemann’s The Member of the Wedding (1952). -Bradford Nordeen

The gears are grinding, the gears of the great and terrible publicity machine, and a comeback by Whitney Houston is said to be in the offing––but what a shame that a star like her has to struggle for a comeback at all. Why can’t she remain, the perfect image of spectacle itself, in our minds forever as the firework that went up, then came down in a glittering shower of sparks? Before her movie career there was the music, and maybe having two careers complicates a comeback prospect. We all know Whitney Houston sure can sing. This unearthly ability tends to supersede everything else. Even in her songs, the voice rises up, into some stratosphere entirely foreign to the lyrics that enable it. You’d think that would make her easier to pin down, because for most singers, the word comes first, and where there’s a word, there’s narrative. But she’s a little different.

Her mentor and producer Clive Davis calls her “the voice,” like she’s some high-octane instrument. As such, there is something linguistically amiss in the content of Houston’s biggest songs. “The Greatest Love Of All,” “I Will Always Love You,” “Saving All My Love For You,” “Exhale (Shoop Shoop),” one never, for a moment, even registers the words Whitney barrels through in her delivery. (During an embarrassing moment at a Karaoke bar some years back, one of us selected ‘I Will Always Love You’ in jest, feeling oh-so familiar with it. Standing before the crowd, the laugh was on us, surprisingly at a loss for words––having no idea of what she actually says in the song.) (Maybe that’s why karaoke posts the lyrics across the screen––supertitles, just for overdetermined situations like this.) Irrelevant as texts, her tracks surge as emotive anthems, as vehicles for “the voice.”

Two pristine images of Whitney compete for the attention of the world. One is an idea of Whitney, non-visually based, just a summation, an essence. It is attuned to the cover of her Whitney album, but that doesn’t say it all. It’s an enormous commitment to the wholesome and the universal. Her songs deftly defy the specificity of race, language, genre (but never gender). Rather like a benevolent version of that thing in The Abyss, an amorphous feeling for Houston creeps over nature and culture, devouring all, making us feel good. It is many things, is any woman––so total is her appeal. The pervasiveness of her stardom tends to subsume her skin color (rarely, during her reign at the top of the movie and pop charts, was Whitney presented as a black entertainer but as Whitney Houston). The second pristine image is that of her specific star image, acutely rendered, lighting perfect, beads in place and a wig to kill for.

Two pristine images of Whitney compete for the attention of the world. One is an idea of Whitney, non-visually based, just a summation, an essence. It is attuned to the cover of her Whitney album, but that doesn’t say it all. It’s an enormous commitment to the wholesome and the universal. Her songs deftly defy the specificity of race, language, genre (but never gender). Rather like a benevolent version of that thing in The Abyss, an amorphous feeling for Houston creeps over nature and culture, devouring all, making us feel good. It is many things, is any woman––so total is her appeal. The pervasiveness of her stardom tends to subsume her skin color (rarely, during her reign at the top of the movie and pop charts, was Whitney presented as a black entertainer but as Whitney Houston). The second pristine image is that of her specific star image, acutely rendered, lighting perfect, beads in place and a wig to kill for.

So how does this translate to film? If, in her songs, the voice mutes the linguistic compositions, how does Whitney function as a cinema star? The cinema of Whitney Houston amounts to a mere four films, though this could be theoretically extended to include the dozens of videos that she’s made––some of them more interesting than her movies. Her videography includes work with Julian Temple, David LaChapelle, Stuart Orme, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Phil Joanou, Francis Lawrence, and dozens more. But who counts those, except insofar as their individual images linger in the air around her like seraphs, helping her ascendance to movie stardom, then marking her fall with averted gaze.

The Bodyguard (1992) was Whitney Houston’s first movie. The Big Chill (1983) scribe Lawrence Kasadan wrote the script in 1976 for Diana Ross to play opposite Steve McQueen. When McQueen was diagnosed with cancer, production went on hold until Ryan O’Neil was proposed. He was romantically entangled with Diana, but when they parted ways, the script landed in a drawer for some time. Nearly 20 years later, the text would be unearthed to launch one of the most profitable crossovers of all time––though it was an artistic achievement only in a limited sense.

The story is a flimsy tale of a bodyguard (Kevin Costner) hired to protect über-starlet Rachel Marron in the months leading up to her appearance at the Academy Awards. Whitney’s own thespian capabilities, surprisingly slim, give her performance a pathetic luminosity––it’s always weird to see a “great actor” played on screen, just as when a novel counts a “great writer” among its characters. They tend to make the mistake of giving quotes from that writer’s greatness. In movie terms the locus classicus is Tuesday Weld as Maria Wyeth in the little-seen 1972 film made of Joan Didion’s Play It As It Lays. In the story, Maria has shot to stardom thanks to a documentary portrait of her made by her filmmaker husband––a cinéma-vérité masterpiece, with Maria displaying this cool It Girl spark à la 1966 Edie Sedgwick in Warhol’s Outer and Inner Space. Unfortunately, Frank Perry includes a reel from Portrait of Maria and we never again believe that Maria ever had anything, so sodden and blank as Tuesday Weld’s misguided performance as a crypto-Edie figure. Test audiences viewing The Bodyguard jeered Houston’s performance, resulting in a hasty reedit and thus birthing a Whitney style of editing: the shot of a shoulder, the back of a head, even attention paid to other characters while the focus is meant to rest upon her––these compose a scene without demanding a corresponding film presence from Ms. Houston, staving off for the one moment in which she will deliver her line.

This Eisensteinian montage of the body builds a delirious anticipation for the Whitney reveal. She’s typically shot in a medium close-up, rendered in shot reverse shot with her screen counterpart. Timing was perhaps Whitney’s biggest challenge, and so, in these distanced frames, Whitney could enact her own sense of time. And this Whitney shot’s careful composure and immaculate lighting is the essence of Houston’s performance––the complete removal from the continuity that surrounds her.

This Eisensteinian montage of the body builds a delirious anticipation for the Whitney reveal. She’s typically shot in a medium close-up, rendered in shot reverse shot with her screen counterpart. Timing was perhaps Whitney’s biggest challenge, and so, in these distanced frames, Whitney could enact her own sense of time. And this Whitney shot’s careful composure and immaculate lighting is the essence of Houston’s performance––the complete removal from the continuity that surrounds her.

Anne Friedberg: The conventions of cinematic representation enforce a metonymy of the human body; a face, a hand, a leg, all cut up. A star, like all human forms in cinema, is not presented as a unified body. In fact, it is often precisely this metonymy which is transformed in to part-object commodities. Garbo’s face is transformed into the most highly commoditized part of her, as are Grable’s legs… The cinema provides part-object identifications, creates part object fetishes.

Yet Whitney is no radiant beauty. Her voice is the stuff of legends, but, as Richard Dyer is quick to remind, “ordinariness is the hallmark of the star.” Here, her use is purely iconographic in terms of her attire and mise en scene. Her appearance is so wholly rendered that the lack of acting capabilities is far more pronounced. She stands erect, looking out over her estate as Maria Montez did, atop her plaster palaces.

Her casting as a successful crossover superstar is ingenious as it not only attempts to codify her lackluster performance as Oscar-worthy, but it renders Houston as Celebrity iconic. Like Houston’s elusion of race, she is not playing Rachel Marron, she is playing Fame. When Rachel steps onto the stage of the Mayan Theater for her provocative performance of “Queen of the Night,” she is not merely Madonna, Cher, Kylie, Diana, and Tina by way of her iconic charge, she is being Whitney Houston. The scene illustrates just how much Houston’s celebrity is a summation of all these figures.

Playing her off Kevin Costner was a defining gesture, for sure. At the time, Costner was America incarnate. In the Seventies, Kasdan insisted the casting be “colorblind.” Right. To watch Rachel, perched in flannel sheets, cradling her son in Costner’s craftsman cottage is to assess in a visual moment what lies at the heart of American perceptions of racism. His world is all snowy and white and steeped in the ruggedness of Americana. She stands out like a sore thumb. The family is “dramatically dark or ‘black’ against the ‘white’ snow,” as Lynne Tillman eloquently observes in her essay on the film. Later she makes it even plainer. “Racial conflict is the unmentionable, perilous secret of The Bodyguard, sitting at the back of the movie-bus, not supposed to be there, not supposed to be an issue.” {Lynne Tillman, “Looking for Trouble (or privileging the subtext),” The Broad Picture, Essays 1987-1996 (London: Serpents Tail Press, 1997).

Three long years later, race receives similar treatment by an opposite means in Waiting To Exhale. In a seemingly odd move, Whitney’s follow-up to the success of The Bodyguard was a “Soul” picture. But, in utilizing an all-black cast, the movie removes racial tension by absolving whiteness from its frame. Though the women do complain about white people, it is rare to catch sight of one in the narrative. By their exclusion, the film creates a world of oneness. Houston reifies her omnipotence.

Even though her Savannah is more mundane than Rachel Marron (she’s a cable segment producer, not the Queen of the Night), she receives star treatment. She’s the first of the four ladies we see, cruising along desert roads in the starriest of non-star convertibles. She’s Grace Kelly, silk scarf enshouding a sunglassed face. Her fragmentation here is beyond belief. As in The Bodyguard, she’s built up via montage––shown only in glimpses. We see her obscured in the car and later, as she prepares for a New Year’s Eve party, she’s shown in parts. She’s slipping on a dress or clasping a necklace––all the while the spectator grows in anticipation, palms itching for our Whitnage. When she finally enters the party and is depicted in full, it is amid twinkling Christmas lights in warm golden hues. She gets two exhales.

Even though her Savannah is more mundane than Rachel Marron (she’s a cable segment producer, not the Queen of the Night), she receives star treatment. She’s the first of the four ladies we see, cruising along desert roads in the starriest of non-star convertibles. She’s Grace Kelly, silk scarf enshouding a sunglassed face. Her fragmentation here is beyond belief. As in The Bodyguard, she’s built up via montage––shown only in glimpses. We see her obscured in the car and later, as she prepares for a New Year’s Eve party, she’s shown in parts. She’s slipping on a dress or clasping a necklace––all the while the spectator grows in anticipation, palms itching for our Whitnage. When she finally enters the party and is depicted in full, it is amid twinkling Christmas lights in warm golden hues. She gets two exhales.

The mystery here is why did it take Whitney so long to make a second movie after the great success of her first, and secondarily, why did she return to the screen in a limited, ensemble part? For those of you who have somehow missed Waiting to Exhale, it tells four stories, all of them of equal weight, and Whitney’s doomed affair with married Dennis Haysbert is just one of them. Is that how a real star behaves, agreeing to a quarter of the screen time she deserves? Or did somebody have something on her? Of course when one looks at the big picture one notes the difficulty any star has in finding a followup vehicle, and women have it ten times worse, and black women, notoriously, fare worst of all when it comes to keeping a screen career going. Dorothy Dandridge, Lena Horne couldn’t do it. Had she actually filmed The Bodyguard opposite McQueen or O’Neal, Diana Ross herself could have continued her screen career, but somehow it just didn’t happen, even with the backing of a powerful studio. When Whitney took Diana’s old role and made a success of it, did Diana wish her well, or did she transfer the curse?

Director Forest Whitaker is creative with Whitney’s shortcomings. Compensating for her poor timing, he puts her on the phone. She yammers away, setting her own pace and you believe her. Aside from these phone sequences, she seldom graces the film’s first hour. In her key, final-act scenes, she’s shown again in medium close-up, in a shot reverse shot with her acting counterpart. Framed solo, Houston exists outside of the narrative, posing as a substitute for the fictional figure, a fetish.

As the Voice robs the innate meaning from its songs by prioritizing form over the content, Houston’s limitations lead the filmmakers to show her as a star in close-up. The Whitney tableaux in the otherwise continuous editing tears the story from the film and renders it a vehicle for her visual.

People found her unbelievable––which she is, but in a purer way than they give her credit for. She’s an unearthly object to be regarded, her screen performances mere afterthoughts.

The success of Waiting to Exhale encouraged the studios to try her out as a romantic lead once more. That’s probably why she made The Preacher’s Wife (1996). Two fabulous women, and too many critical snubs took Whitney to a more humble, family-oriented role. She’s quite good in it and it’s truly refreshing when she just lands onscreen in the film’s first minute. She seems earnest and unpampered, tucking in her child and helping her husband keep his faith. Penny Marshall’s remake of a Goldwyn film from the late 40s divided critics and audiences. There will always be those who can’t abide the idea of a remake, any remake, even one of a movie not particularly remembered as a great classic. And these purists were aghast at the Marshall plan to re-cast Loretta Young, Cary Grant, and David Niven with Whitney, Denzel Washington, and Courtney B. Vance. Myself, I didn’t think it so bad, it’s not like the original Preacher’s Wife (then called, more grandiosely, The Bishop’s Wife) was any Casablanca or anything. It was just a serviceable whimsy about a married couple losing that spark while staying true to their religion. Then an angel comes to earth, charged with helping them out, but as it happens he’s a man too (excuse me?) and falls a little in love with the earthly, married lady. For me, Cary Grant––I could take him or leave him, and as an angel he really makes my teeth rattle.

The success of Waiting to Exhale encouraged the studios to try her out as a romantic lead once more. That’s probably why she made The Preacher’s Wife (1996). Two fabulous women, and too many critical snubs took Whitney to a more humble, family-oriented role. She’s quite good in it and it’s truly refreshing when she just lands onscreen in the film’s first minute. She seems earnest and unpampered, tucking in her child and helping her husband keep his faith. Penny Marshall’s remake of a Goldwyn film from the late 40s divided critics and audiences. There will always be those who can’t abide the idea of a remake, any remake, even one of a movie not particularly remembered as a great classic. And these purists were aghast at the Marshall plan to re-cast Loretta Young, Cary Grant, and David Niven with Whitney, Denzel Washington, and Courtney B. Vance. Myself, I didn’t think it so bad, it’s not like the original Preacher’s Wife (then called, more grandiosely, The Bishop’s Wife) was any Casablanca or anything. It was just a serviceable whimsy about a married couple losing that spark while staying true to their religion. Then an angel comes to earth, charged with helping them out, but as it happens he’s a man too (excuse me?) and falls a little in love with the earthly, married lady. For me, Cary Grant––I could take him or leave him, and as an angel he really makes my teeth rattle.

I’d rather have Denzel any day, though Courtney B. Vance as the preacher is a little dusty drab. (Isn’t he the one married to Angela Bassett? What’s THAT about?) Whitney gets promoted here to be the head of a rockin’ soul choir like the one Lily Tomlin leads in Nashville. It is funny, with her penchant for being photographed in the snow, that the whole film takes place in winter. In one scene, Denzel literally drops onto the ground on his back, in a yard filled with snow, and experimentally moves his arms and legs in the way that, when we were children, we called making snow angels.

But it doesn’t last long, as it was followed by the TV movie Cinderella (1997), which Whitney co-produced with Disney. This role is the filmic Whitney bible. It’s also her final film role, as she returned to the pop charts the following year, confiding in her fans, “It’s not right, but it’s ok.” She plays Brandy’s Fairy Godmother, enabling her to enter and exit the narrative at her leisure. Her tableau is fantastically exaggerated by the dictates of Disney’s visual effects. She must remain in place, stoic––lest Disney’s wisps and plumes of magicness land in improper places. She speaks in monologues, and it is her Fairy nature to burst into whimsical song. She arrives in clouds of smoke and, in the exhilarating final sequence, soars above the palace, trailing streams of flaming magic beyond the highest turret like some diva-phoenix. She blasts her signature voice and the otherwise bizarre film makes all the sense in the world.

Cinderella is also most illuminating considering Whitney’s perpetual casting as colorless. The film portends to be colorblind, or, as the boxcover informs, is told with a “modern twist.” In fact it’s known as “rainbow casting,” and Robert Iscove’s inventive film, with choreography by future director Rob Marshall (Chicago), is often held up as the primary example of this. Thus Whoopi (black) Goldberg and Victor (white) Garber as the Queen and King, have a handsome South Asian son (Paolo Montalban, born in Manila). It makes emotional sense, its proponents explain, even though Gregor Mendel may not like it. Cinderella herself is played by the young Afrian-American performer Brandy Norwood. But when a black actor is oppressed by a white wicked Stepmother (Bernadette Peters), her role becomes overtly slavey. It’s like a Kara Walker version of Rodgers and Hammerstein, and more power to the designers. And so the film extends a grotesquely placating gesture, viewing race “arbitrarily.” The white slaveowner/stepmother has an obese black daughter––to offset Cinderella’s racial and sexual charge? It’s hard to say, but when Whitney appears to Brandy in an explosion of CGI and sleekly manicured R ‘n’ B, she gives her fans what they really want––the fabled “Look of Superiority.”

Cinderella is also most illuminating considering Whitney’s perpetual casting as colorless. The film portends to be colorblind, or, as the boxcover informs, is told with a “modern twist.” In fact it’s known as “rainbow casting,” and Robert Iscove’s inventive film, with choreography by future director Rob Marshall (Chicago), is often held up as the primary example of this. Thus Whoopi (black) Goldberg and Victor (white) Garber as the Queen and King, have a handsome South Asian son (Paolo Montalban, born in Manila). It makes emotional sense, its proponents explain, even though Gregor Mendel may not like it. Cinderella herself is played by the young Afrian-American performer Brandy Norwood. But when a black actor is oppressed by a white wicked Stepmother (Bernadette Peters), her role becomes overtly slavey. It’s like a Kara Walker version of Rodgers and Hammerstein, and more power to the designers. And so the film extends a grotesquely placating gesture, viewing race “arbitrarily.” The white slaveowner/stepmother has an obese black daughter––to offset Cinderella’s racial and sexual charge? It’s hard to say, but when Whitney appears to Brandy in an explosion of CGI and sleekly manicured R ‘n’ B, she gives her fans what they really want––the fabled “Look of Superiority.”

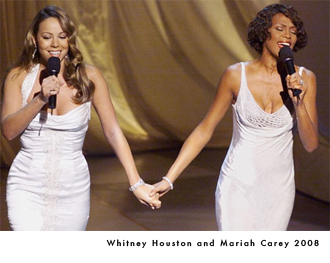

The “Look” is the thing fandom is made from. You see it everywhere in Whitney’s career, and it’s not especially pretty. To make a long story short, it’s a facial expression you see on Whitney Houston when she’s dueting with an inferior partner, and since nobody can match her lungpower, they’re all subject to the notorious withering “Look.” YouTube has a great video in which Whitney is dueting live with Mariah Carey on their theme from The Prince of Egypt, the minor-tinged, insipid “When You Believe.” Mariah is no slouch with trills, of course, but she is simply overpowered in the later, gospel choruses of the track, and Whitney, bellowing loud enough to be heard on Mars, is never too busy to simultaneously flash Mariah the malignant, triumphant, “Look of Superiority” we love. Poor Mariah’s fear shows through her smile. Go ahead now, Google “Look of Superiority” + “Mariah.” You will not believe your eyes!