The Object is Not the Art

16.02.12

I officially met Truong Tran last year at one of the Living Room Series readings held at his home on Ashbury Street [San Francisco]. His delicate-looking art jutted from living room walls, and though fragile, upon closer look it contained vulgar and jarring imagery. I knew I was encountering someone with a fertile playfulness. I had also heard that he had published five books of poems and a children’s book. His prolific nature intrigued me, as well as his modesty and sociability when I first spoke to him.

I officially met Truong Tran last year at one of the Living Room Series readings held at his home on Ashbury Street [San Francisco]. His delicate-looking art jutted from living room walls, and though fragile, upon closer look it contained vulgar and jarring imagery. I knew I was encountering someone with a fertile playfulness. I had also heard that he had published five books of poems and a children’s book. His prolific nature intrigued me, as well as his modesty and sociability when I first spoke to him.

As the months have gone by since then, I’ve been fortunate enough to speak with him many times about his perceptions of art and poetry. And to simply joke around with him. He’s often jolly.

His second big exhibit just launched at SOMArts in San Francisco, called At War. His art will remain there until February 29th, so if you’re in the Bay Area this month I recommend you check it out.

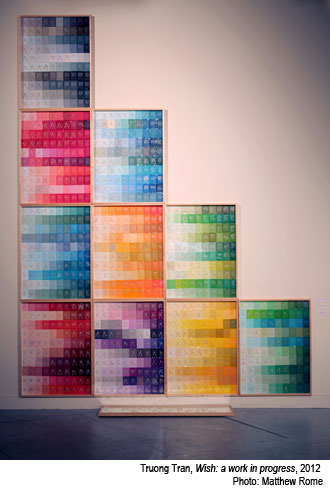

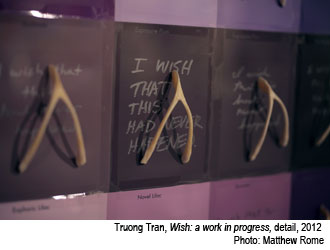

On opening night, I arrived to see his side of the gallery glowing with lit-up images, projected videos, paper cranes, and an immense piece consisting of vividly-colored squares with “I wish that this had never happened” scrawled on them. In front of each colored square, which were encased (as the majority of his art is), he had placed 600 chicken wishbones. This piece, called Wish: a work in progress, due to its massive size and irony resonated with me most. A friend of mine pointed out that one square read, “I wish I was happy.” As I found out later, Truong loves to hide things in his art. Whether it’s one of hundreds of squares that says something different than the rest, or shocking images that can be made out only upon close inspection, he thrives off providing a veil for the viewer. As I also found out later (from the video tucked away in the corner room of the gallery), he manually cut out each wishbone for this piece.

Apart from the intriguing repetition and sheer magnitude of his art here, I began thinking about the title of the exhibition: At War. I approached him about it––about his vision of the show. He said, “It’s all in the Camus quote.” He was referring to the quote on the main sign at the entrance, that reads, “Accepting the absurdity of everything around us is one step, a necessary experience: it should not become a dead end. It arouses a revolt that can become fruitful.” Further, I asked him why so many of his pieces invested in obscuring images, in placing layers in front of the images in order to skew them. He said he wasn’t trying to obscure them but to “veil” them, that just as media veils the absurdity of war from us he was veiling these (often homosexual pornographic) images.

I wanted more insight into his process, his motivations. And his show became more and more crowded. It wasn’t an appropriate atmosphere for me to ask him questions and hope for elaborate responses, so we scheduled a time for me to come to his art studio on Mission Street two days later. I was stoked.

I wanted more insight into his process, his motivations. And his show became more and more crowded. It wasn’t an appropriate atmosphere for me to ask him questions and hope for elaborate responses, so we scheduled a time for me to come to his art studio on Mission Street two days later. I was stoked.

When I arrived at his studio, I saw a piece made from syringes and one from crack pipes, both of which exhibited his characteristic repetition and absurdity. His big windows looked out on the Mission.

Here’s some of what followed from my interview with him:

Matthew Sherling: So, how long have you been making visual art?

Truong Tran: In earnest, probably about five years now.

M: What do you see as your main shifts from writing poems to focusing more now on visual art?

T: I think it got to a point where I didn’t trust language anymore, so I wanted to do something outside of it that would push me away from language.

M: What was lacking in language?

T: I think the business of poetry was very difficult for me. “Po-biz” as they call it. It just felt like my own work was trying really hard to resist falling into that mode of being academic, and I thought the best way to do that was to give myself space from it. I mean, honestly, when was the last time you read a book by an author––maybe Diana Salier is the one [we had spoken about her earlier]––who didn’t go through a program, who didn’t write from that kind of headspace? Our society now is so driven by that. You know, I’m saying this as a teacher in an MFA program.

M: [laughs] Right, so what capacities does visual art have that language doesn’t have?

T: I can only say for me personally, but I think it can be more playful. I mean, I’ve always been playful with my writing––playing with the space––but I think in visual art the access of materials allows access to irreverent materials.

M: You love irreverence. I’ve noticed that. Why is that?

T: I think art needs to be difficult. It has to be jarring. I think commercial art in our society equates art with taste. I don’t think the two have anything to do with each other [laughs]. I don’t think art should be about taste. The minute that you do that, art is created, you know, to fit behind a red couch. And that’s not art.

T: Edmond Jabès. He has this amazing excerpt that I always share with my classes.

[He pulls out a book1 and reads this passage]:

***

“A good reader is first of all a sensitive, curious, demanding reader. In reading, he follows his intuition.

Intuition––or what could pass as such––lies, for example, in his unconscious refusal to enter any house directly through the main door, the one that by its dimensions, characteristics and location, offers itself proudly as the main entrance, the one designated and recognized both outside and inside as the sole threshold.

To take the wrong door means indeed to go against the order that presided over the plan of the house, over the layout of the rooms, over the beauty and rationality of the whole. But what discoveries are made possible for the visitor! The new path permits him to see what no other than himself could have perceived from that angle. All the more so because I am not sure that one can enter a written work without having forced one’s own way in first. […]

***

I think this is an amazing document to have. I spent years trying to understand the work of others as they would want me to understand it. But it has to be understood by you, by yourself. You have to give yourself permission. And I think that’s the same thing I’m trying to do with my art.

I mean, at the show, when people encounter that bag of gift-wrapped boxes. They have questions as to what is the art there: is it the boxes? Is it the bag? But the real art there is, is someone taking the box? That’s what enacts the art. Do you take it or not?

M: I saw a little girl take one of the paper cranes at the show. And I was thinking, Would he care if someone did that? And I asked Rod, and he said, No, he would love that!

T: That’s right. It’s what’s supposed to happen. I don’t believe in the preciousness of art. It may look organized and contained and perfected, because I’m obsessive. But ultimately, it’s an object. And the object is not the art; it’s the relation one has to the object that is the art. I want the viewer to arrive at their own conclusion of whether it’s art for them or not. I think we often think something’s art because it’s pretty. But real art is difficult. It should have at once an attraction and a repulsion.

M: Interesting. Can you say a bit about the wishbone piece?

T: I had the original idea to, over a twenty-four hour period of time, run a soup kitchen as performance art. I would feed people. And in exchange for being fed people would give me a wish that I would tag to the piece. And it’s something that may still happen. I’m not finished. I had 800 wishbones, and I have 200 more.

__________

1From the Book to the Book: An Edmond Jabès Reader. Trans. Rosmarie Waldrop. Wesleyan, 1991.

M: So on each colored square, the text reads, “I wish that this had never happened.” And there was one that reads, “I wish I was happy.”

M: So on each colored square, the text reads, “I wish that this had never happened.” And there was one that reads, “I wish I was happy.”

T: Yeah, “I wish I was happy,” “I wish I was a porn star.” That was me just being a smartass. I hide things. I’m really fascinated with the idea of hiding things inside of things.

M: The other piece that resonated with me was the soldier piece––the nude picture of Alex.

T: Yeah, and that was all by chance. I met Alex at the Fourteen Hills launch and, I didn’t know it but he had been at my house to see Dan Langton read. He sat down next to me, and when he told me he was soldier––it was interesting––that was the only perspective I didn’t have. It’s easy to be critical of the war, and it’s something I was doing very clearly in the show. And the politics of it. But having someone who was a soldier in the war kind of changed that perspective a bit. It needed to be in the show.

M: Absolutely. So, can you say any more about the veiled politics thing? You’ve mentioned that your last book was concerned with that as well as this show.

T: Yeah, yeah, it should be pointed that 99% of all the images from the show were from the Internet. And what I juxtapose quite a bit are the images of war and porn. Some people might say, “Oh, he’s interested in the politics of porn.” And that’s not true: I’m not interested in the politics of porn. I’m interested in pointing out the fact that the government invokes the intimacy of two men as a way of diverting attention from the real pornography of our society, which is the proliferation of war and destruction. You see it all the time. When there’s an election, you can rest assured that gay politics will enter in somehow. And that is the veil. Diverting attention. And it’s a very sensationalized notion. It’s never presented as the intimacy of love. That’s why when I chose the images for the art, I chose really really outlandish images. It’s almost like a Botticelli painting––it’s so staged. In the same way that the images of war are so staged. Those are actually images we got off the Internet. Many of them were from government websites, and they look very staged or posed. And there’s a lot of glory embedded in those images of war.

To me that’s really pornographic. I think a lot of dudes in Middle America might look at that and say, “Yeah!”