Articulatory Organs and Hindi Sounds

02.03.15

A. As a speaker or teacher of Hindi will often state, Hindi is a very scientific language.

B. I’m not sure how a language can be “scientific.” I think by “scientific,” those who advocate for Hindi usually mean “uniform.” The rules for Hindi are fairly hard and fast. Once you learn the Devanagari script and the pronunciation of vowels and consonants, it’s sort of smooth sailing from there.

C. Hindi is (one of) the national language(s) of India, as “Indians would…say with pride if they are from the north and with a good-natured grouse if they are from the south,” claims Manu Joseph, writing for the New York Times. This north-south separation, marked especially by the Hindi-Tamil linguistic divide, creates a division between regions, prominently noted in the recently released runaway Bollywood smash-hit 2 States.

D. According to Snehamoy Chaklader, writing in Language Policy and Political Development, “Hindi…is not compulsorily taught at any level of education [in India].” Regional languages, like those spoken in West Bengal, Chaklader’s area of focus, instead tend to dominate in the educational sphere, although Hindi remains one of the foremost “official languages.”

E. Urdu is the national language of Pakistan, a nation created via the violent partition of India in 1947.

F. I’m told that Urdu and Hindi are virtually indistinguishable when spoken; yet, when written, the former takes on the curved shapes and dashes of Arabic, while the latter sports a “clothes-line” that letters hang off of in Sanskrit-derived tongues. Speakers of Hindi and Urdu maintain the distinctness of the two languages, to a point where Urdu-speakers express surprise if you tell them a word in Hindi and they hear it as the same word “in Urdu” – and the other way around as well.

G. Difference between the languages do persist, however, even in the spoken form.

H. I Googled “Hindi is a scientific language” to make sure I wasn’t making up that comment, although I believe I’ve heard it before from several teachers.

I. What I found, instead, was a book-length study on the short story by Christine Everaert, who reveals, “authors, when translating their own texts from Hindi into Urdu or vice versa, often make changes to the texts which can be more far-reaching than outside translators. In this way, authors change the meaning, interpretation, and even the plot of the story.”

J. In translating my experience with Hindi to this alphabetical essay, I may, too, even be altering the plot of the story to match its sounds.

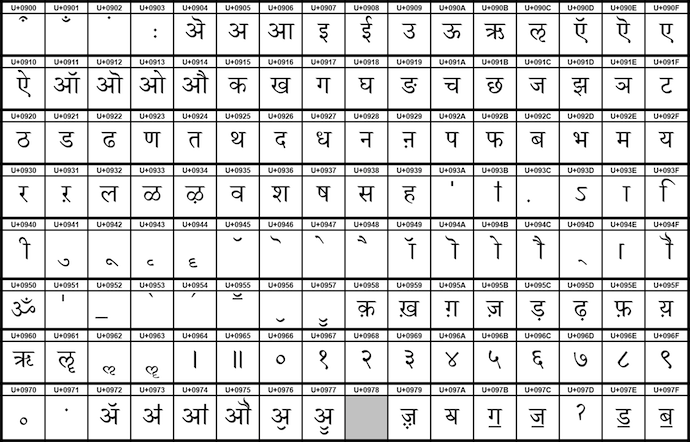

K. Retroflexes are the hardest sounds to pronounce for non-native speakers. The retroflex sounds include ट ठ ड and ढ. There are no retroflex consonants in English, though there are close approximations, like the “d” in “drum.”

L. The place of articulation, the origin from where the retroflex sounds bang out, is located in the back of the alveolar ridge. Most of the retroflexes in Hindi are pronounced like the word “duh,” as if the language itself is taunting you.

M. Pronouncing the dental sounds, unlike retroflexes, forces your tongue to touch your upper teeth, like you’re sticking out your tongue. As in “thing” or “this.” Duh.

N. The Economist states, “Indian retroflexes are fun to produce. Curl your tongue back and strike your palate, and you’re in position to articulate one.” Of course, The Economist‘s idea of “fun” might be different from what most folks think of as fun.

O. Remember, this is also a publication that reports country currency data using a “Big Mac” index, an economic comparison system “based on the theory of purchasing-power parity (PPP), the notion that in the long run exchange rates should move towards the rate that would equalise the prices of an identical basket of goods and services (in this case, a burger) in any two countries.” Fun.

P. Some retroflex sounds require aspiration and others do not. When you pronounce “aspirated” sounds, breath tumbles out of your mouth. When you’re learning to differentiate between “aspirated” and “unaspirated,” you can hold your hand in front of your mouth to feel the air exiting or not exiting. In a plosive consonant, like the letter “P,” airflow is stopped.

Q. As our teacher explains, seeing us students raise our hands to our mouths as we “aspirate,” it’s not as if Hindi is spoken with your palm sealing off your lips at all times.

R. Learning a new language, as pretty much anyone will articulate if they’re an adult, is like being a child again. You do a lot of pointing and mispronouncing. Your hands transform into overexpressive actors.

S. During our first class, our teacher honestly invented and wrote nonsense tri-syllabic words in the Devanagari script on the board just so we could learn to pronounce new consonant sounds strung together. We were saying nothing, in unison. A blanket of Hindi white noise.

T. Singing the English alphabet, though instructive, becomes a terribly depressing cyclical action. Just try warbling “next time won’t you sing with me” and feel your adult body absolutely refuse, under any circumstances, to start at A again.

U. Feeling like a child again is also incredibly frustrating. Art, some would claim, is about an attempted return to childhood. A range of artists wrestle with this philosophy: from Cy Twombly to Proust to Virgil writing about the utopic arcadia. The paradise of being young, ignorant, and free. An Eden without knowledge; the coziness of the unaware.

V. I remember feeling impossibly, hopelessly frustrated as a child. I wasn’t able to pronounce a desire, I didn’t use the correct social cues, and the world appeared like a mess of codes I couldn’t write. And, as an ignorant only child, my perspective turned solipsistic. I loved books because they took me seriously, even when I was alone.

W. Productive texts don’t belittle the reader. This is possibly why writers like Aimee Bender and Ben Lerner have revealed their fascination with Margaret Wise Brown’s Goodnight Moon: it’s a weirdo existential tome masquerading as “children’s literature.” Don’t talk down to kids, because, even if they can’t talk back, they understand you. They simply can’t translate back yet.

X. When I lived with a Jaipur-based family who primarily spoke Hindi, I still understood familial situations, even when the language escaped me. When the son wanted to go out with his friends but the mother insisted he stay for family dinner, even if family dinner consists of watching Zorns Lemma with English subtitles, I perceived and received this dynamic, at least to an extent, only through interpreting hand-motions and eye-rolls and this little head-shake that’s not quite a nod and not quite a “no” many Indians practice, in response to most, if not all, questions and statements.

Y. Not quite a yes and not quite a no. The Hindi word that sounds like “kul” – कल – means both tomorrow and yesterday and the day before.

Z. Of course, context tells you where the past, present, and future are located in a sentence. It all depends on the ending of the verb, if you understand its language.

—————-

Sources and references:

Everaert, Christine. Tracing the Boundaries between Hindi and Urdu: Lost and Added in Translation between 20th Century Short Stories. Brill, 2010. Brill E-Books. January, 2010. E-book.

Jain, Usha R. Introduction to Hindi Grammar. Berkeley: Center for South Asia Studies, University of California. 1995. Print.

Manu, Joseph. “India Faces A Linguistic Truth: English Spoken Here.” February 16, 2011. URL: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/17/world/asia/17iht-letter17.html

Chaklader, Snehamoy. “Language Policy and Reformation of India’s Federal Structure: The Case of West Bengal.” Language Policy and Political Development. Ed. Brian Weinstein. 1990. Print.

—————–

John Rufo reads and writes poetry at Hamilton College. His work has been previously published, or is forthcoming, in Ploughshares, Prelude, Entropy, Queen Mob’s Tea House, and HTMLGiant. He interns for Maggy and co-runs Red Weather, a literary arts magazine, with Zoë Bodzas. You can hang out with him online at dadtalkshow.tumblr.com.