Savage Park: An Interview With Amy Fusselman

03.03.15

Amy Fusselman became something of a cult favorite with the publication of her first book, The Pharmacist’s Mate, a pulsing mutant of a memoir that layers excerpts from her late father’s World War II journal underneath her struggles to become a parent herself. A former punk guitarist and editor of the vine BunnyRabbit and literary web site, Surgery of Modern Warfare, Fusselman’s work maintains a punk ethos of irreverence and rawness that rebels against almost all the commercial protocols of publishing. Through memories, manifestos, and random ruminations on everything from sex salon furnishings to the lunacy of motherhood, Fusselman writes with unabashed joy about our beautiful, weird lives.

Amy Fusselman became something of a cult favorite with the publication of her first book, The Pharmacist’s Mate, a pulsing mutant of a memoir that layers excerpts from her late father’s World War II journal underneath her struggles to become a parent herself. A former punk guitarist and editor of the vine BunnyRabbit and literary web site, Surgery of Modern Warfare, Fusselman’s work maintains a punk ethos of irreverence and rawness that rebels against almost all the commercial protocols of publishing. Through memories, manifestos, and random ruminations on everything from sex salon furnishings to the lunacy of motherhood, Fusselman writes with unabashed joy about our beautiful, weird lives.

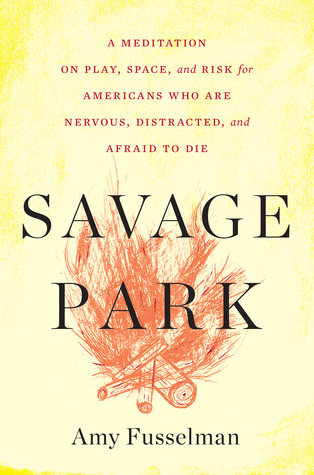

Her latest book, Savage Park, is a poetic inquiry into the theoretics of play and space, the catalyst of which is a family trip to Tokyo where the author’s hostess introduced the Fusselmans to a massive play park that’s more Lord of the Flies than “Parks and Recreation.”

On her first visit, Fusselman is shown an unsupervised hut housing hammers, nails, and box cutters for use on the raw pieces of lumber lying all about, and a massive field where open fires and tree climbing are de rigueur. After befriending the park manager and understanding more about the philosophical tenets upon which the park is based, Fusselman returns to the United States with her theories about personal safety and what constitutes “play” overturned. Savage Park is the product of the several years she spent ruminating on what she saw and learned in Japan.

COURTNEY MAUM: Savage Park deals in a large way with what we understand children’s play to be in America. You’re the mother of two young children in an urban environment. After your visit to Tokyo’s Hanegi Playpark and the research you did for this book, did you make any changes in respect to the way your own children play?

AMY FUSSELMAN: Yes, this project made a huge impact on the way I view play and how I try to support it in our family, which has grown to include three kids. Brian Sutton-Smith, in his fantastic book, The Ambiguity of Play, questions whether the dominance of the rhetoric of play as progress—the idea that children adapt and develop through their play—has “disguised the understanding of what childhood is about as a way of maintaining adult power over children.” I think his book should be a parenting manual.

The psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott wrote that it is in playing, and perhaps only in playing, that adults and children are free to be creative. As a result of this project, I have become more devoted to making play happen for myself and my children. I am more tolerant of my kids’ play-related mess, for instance, and more likely to ask whether we should save a project in progress. And I’d say I play more myself. Right now we’re in a phase where my right and left hands are named Freddy and Jimbo and they and my daughter talk a lot. Freddy is a straight man and Jimbo has watched a little too much Triumph.

CM: Let’s talk about your prose style a bit. You have a very distinctive style—at least in what I’ve read of you (8, The Pharmacist’s Mate, Savage Park), your books are composed of brief meditations—often on different subjects—that contribute to a larger theme or even mood. Have you always written in this interrupted way? How much editing goes into each of the meditations? Do you start out with a larger chunk of text and whittle it down, or does everything come out this cool and clean?

AF: Thank you for that compliment. The books are superconstructed. The sections of text are closely edited and deliberately placed. That process of composition is one of the primary joys of the work for me. I studied poetry writing in graduate school and I found the seed of this form during that period. My books operate as prose poems. For that reason I don’t think of this writing style as interrupted. Maybe the texts are constructed in a way that’s surprising for a reader who is expecting the prevailing form. But I am the sort of reader who likes to be surprised.

CM: In a prior interview with BookSlut before The Pharmacist’s Mate’s re-release with Penguin, when asked whether you write fiction, you responded, “I don’t think I’m capable of something purely fake.” Can you expound on this? Do you still think of fiction as fake?

AF: What I meant at the time was that I wasn’t then capable of working with a narrative that was made-up. I wouldn’t say that now. For one thing, I’m a better writer. And of course good fiction has truth at its core— that’s why we love it and why it resonates.

CM: You have a musical background as a punk guitarist. Does music in any way influence your work?

AF: My past experience in bands is something I treasure and I do believe that it has informed my working process. When I write, I sometimes feel like I am recording, as in recording a track. I can tell this is happening when my listening seems amplified. I write by ear, and when I am writing well, I feel that same “recording” feeling of listening very closely to what I am making. I consider it to be a good sign when that happens.

CM: The parts about your classes with the famed French high wire artist Philippe Petit in “Savage Park” were fascinating, but it wasn’t clear to me what lead you to take those classes in the first place. Were you there for research or for fun?

AF: I don’t think of research and fun as either/or. In the second paragraph of that passage I write, “I was there to learn about space from someone who clearly has a genius’s understanding of it.” That Philippe Petit looked at the negative space between the World Trade Center towers and saw that as a valid field of operation was exactly the kind of creative perception of space that I was interested in. I also love his understanding of creativity as something that is fundamentally transgressive. His recent book on the subject frames it as “a perfect crime.” In it, he uses the metaphor of the creator as outlaw to write about the tenacity and subversiveness required to bring artistic dreams to life. That framing seemed particularly apt while as I was working on Savage Park and confronting the poverty of a typical playground space.

CM: Your writing is never prescriptive. It’s a gamble in today’s market, writing creatively in a way that requires that readers reflect, ask questions, and in short, work to get the most out of what they’re reading. Have you experienced any pushback about your fairly open-ended style?

CM: Your writing is never prescriptive. It’s a gamble in today’s market, writing creatively in a way that requires that readers reflect, ask questions, and in short, work to get the most out of what they’re reading. Have you experienced any pushback about your fairly open-ended style?

AF: What you’re calling work, I think of as play. My hope is that people will find reading the books to be exciting. Some people obviously won’t, though, so if by pushback, you mean “Does the writing have detractors?” then, yes, of course. That comes with the territory.

CM: Let’s talk about length. Your books are slim, but not necessarily concise. That is—they leave a lot of room for interpretation so they are, in fact, much longer than they appear to be. But still—to a passerby in a bookshop, say—they’re going to appear short. Why are your three published books the length they are? Does it have to do with subject matter, aesthetics, stamina?

AF: I write until the piece is finished. That is my sole directive. I try not to pay too much attention to how books should be. I don’t think that’s helpful creatively.

CM: To what extent were you inspired or influenced by your time in Japan, outside of your time in the Hanegi Playpark? Are you working on anything else that has to do with your time in Tokyo? I was very moved by the friendships you formed, most notably with Noriko, the park’s playworker.

AF: I am a Japanophile like a lot of people. I was fortunate enough to see some sumo wrestling when I was there and I could have watched that for days. I am also obsessed with ramen and we are lucky to have some great ramen places in New York City. I would love to go back to Tokyo and I would love to see Noriko and her family. I have several projects in the hopper but none of them deal with Tokyo.

CM: What question do you wish more interviewers would ask you?

AF: I edit an online art and literary journal called Ohio Edit and we recently released our first publication for sale—a 99-cent downloadable essay by London Review of Books publisher Nicholas Spice called Winnicott and Music. It’s a beautiful piece of writing that offers several provocative ideas about the way we listen to, talk about, and learn music. I am very excited about it.