Marque of Goodness

20.05.10

I valued what was good in Mrs. Fairfax, and what was good in Adele; but I believed in the existence of other and more vivid kinds of goodness, and what I believed in I wished to behold.

—Jane Eyre, from the book Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte

Beauty is the harmony of chance and the good.

—Simone Weil

Some of the good things in this life are material things. Some of these materials are art and fashion and jewels. Some of the materials are not material, like goodness, and a persistent allure that seduces and degenerates the real so that its sheen of good qualities reflect upon the mob the image of their ideal.

Vast audiences want to behold goodness like Jane Eyre wants to behold goodness. Goodness implies an innocent- forever aloofness about anything that isn’t it. Something like an accidental good art can happen when one isn’t worried too much about doing anything but parading their own goodness. There is a current of regality to goodness, a superabundance of beauty unto waste, prey to one obstinate dream. Goodness has to do with the heart, and the good work of the heart that can find its way into art is a rare goodness. To design work with the good heart. To impute a touching sensuality to the work of good art because it is of the nature of goodness to be all good, like wholly your body and soul good. The mind is sometimes an impediment to goodness because it makes one think. Pure goodness does not have to be thought about. Some things that are good are pretty things like clothes and jewels, sweet and good things like keepsakes and prescriptions that make you feel good, or legal documents that free you or make you good and rich. Goodness can be formless and shapeless, elusive and pleasurable. Makers don’t think about goodness enough when they try to create a work of artwork. Good being a characteristic not beneath great, but something greater than great. Great is beholden to goodness. Goodness resists classification because of its ubiquity, ubiquity being like “Sound and Vision” played from an Icelandic eider down cloud in heaven for everybody everywhere to hear. Deliberately understated, goodness cannot trump itself so it does not try. It cannot always be aware of its goodness so it will be, just plain good. It cannot refer to itself, it must be like a heaven that is to die for.

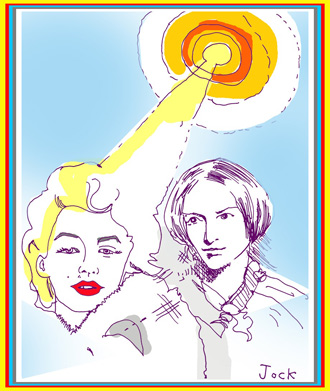

Marilyn Monroe is good. That is true. And Marilyn Monroe was into jewels and clothes and channeled goodness through her body. Marilyn Monroe was famous for being good. Maybe Jane Eyre longed for Marilyn Monroe to appear among the busy world. Goodness is ultimately rich, too rich to really even look at sometimes, like the sun. There is a lot of sun in Los Angeles, and maybe it is the source of all goodness. Maybe the goodness in art, and the goodness inside of one that makes it possible to make good art really comes from standing directly under the sun all the time. The sun kind of solicits you in the instance of standing under it in the magical moment that you are in the process of creating a work of art that is so good it will be like the bejeweled heaven that holds the sun. I think that the sun can be seen and can be reflected in good material things that are the product of essential goodness. Sometimes these things can be found on bright walls, sometimes they can be found on a person’s person, sometimes they are found on gleaming racks, sometimes they are found in cathedral vaulting, sometimes they are found in a motion pictures theater, right now they are found in a book, The Ravenous Audience, displaying an excellent written work called “Marilyn: Leftovers” by Los Angeles-based writer and performer Kate Durbin who writes poems about the House of Viktor & Rolf and other forms of goodness that would make Jane Eyre blush redder and feel like it is all good and worth it.

“Marilyn: Leftovers” is an exhaustive textual sensation cataloging the good things that Marilyn Monroe chanced to leave behind. It’s sorted into five sections: The Clothes, The Jewels, The Keepsakes, The Prescriptions, The Legal Documents. These sections, in paragraph blocks and syntactic units, contain the material items pertaining to their heading. Below is a passage titled “The Jewels”:

a collection of necklaces bracelets earrings and brooches a gold necklace possibly by Paul Flato from the early 1960s the long chain is hung with stylized “lily” drops a necklace with a diamond center stone a jade beaded necklace a link necklace with a square clasp a jade beaded necklace with a gold flower clasp a diamond necklace with a diamond and ruby pendant a pearl necklace with a pearl and diamond pendant a pearl necklace a diamond art deco-style necklace a pearl necklace with a flower clasp a Blancpain diamond watch a Marvin diamond and gold watch gold ear clips pearl and gold cluster earrings pearl drop earrings diamond and pearl cluster earrings pearl and gold pineapple earrings diamond and gold starburst brooches a pearl and gold brooch a pearl brooch a pearl and gold pineapple brooch a diamond and gold brooch a diamond and gold-link bracelet a four-stained pearl bracelet with a gold clasp a diamond and ruby bracelet a jade and gold bracelet

Kate Durbin, who recites and performs this distraction with a surfeit of pleasures like it, will not maintain an audience unless decorously dressed in spectacular costumes of vintage gold lamé, feather eyelashes, butterfly dresses, lengthy exquisite gowns, pervasive doll-like makeup, gauntlets, stockings, satins, or hoods. The costumes more than compliment the written work, they are a primary gesture in Durbin’s practice. Beyond writing, Durbin enchants the mob, precipitating a trance-inducing litany of bling, vogue, and the content of image. Being of total goodness alleviating total absence, at the precipice of panic, where tableaux vivant might break out into dance, Durbin trespasses beyond the closely restrained writer-unto-reader schemas to inspirit her audience toward a more intuitive style-is-substance reception of the written works.

Why do people want to look at art that doesn’t move? Marilyn Monroe moved, models move, pageants move, movies move. Written works typically don’t move. They are usually immovable and flat, unlike money and jewels that rattle around in people’s pockets and on their necks and faces. In “Marilyn: Leftovers” Kate Durbin has amalgamated perennial good vibes into a good poem that is like a new way in American poetry that is about not doing stuff that doesn’t move people, move bodies, move clouds, move jewels, move markets, move fabrics, move vividly, move cascades of people that move around wearing moving and elegant dress, touching and gliding softly into the future that doesn’t want the bad art to be so bad and motionless and stationary. The universe wants the good art that can come from the good places inside where nothing really matters but the vain dreams in your heart that never die, that renders obsolete so much art that isn’t obsolete yet. Art that imprisons and kills dreams, making people want to wear bad clothes, go around unmade up watching uninspiring movies, and looking at uninspiring stases that do not emit the classic fluids is not good. Kate Durbin is good.