All The Things We Cannot Know: A Review of Sunshine State

20.06.17

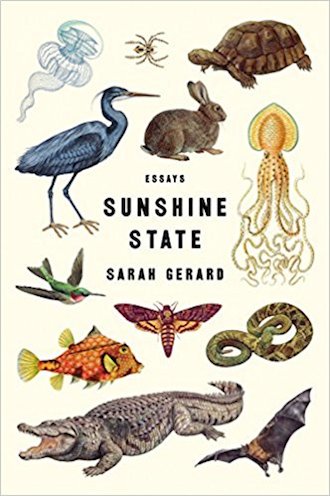

Sunshine State

Sunshine State

by Sarah Gerard

Harper Perennial

384 pp. / $15.99

In Leslie Jamison’s “Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain,” she writes “…I don’t believe in a finite economy of empathy; I happen to think that paying attention yields as much as it taxes. You learn to start seeing.”

There is an importance to seeing and being seen that is difficult to explain to those who have always been in focus.

In Sunshine State, Sarah Gerard writes essays that feel incredibly personal without spending too much time on herself. She is a thoughtful observer who often turns inward, but it’s always to clarify, to reflect, to linger.

The collection alternates straight memoir of her youth in Florida with longer, more journalistic pieces, about people and institutions that have roots in the state.

Gerard is present in all of them, smoking cigarettes with her subjects, comparing her experiences to those she’s observing, but her voice is never the loudest. She never speaks when someone else is talking.

This is especially evident in the title essay, “Sunshine State,” which is ostensibly about a bird sanctuary. Over 55 pages, Gerard unravels only a small thread of the densely knit mysteries of the Suncoast Seabird Sanctuary (which, in a move that will surprise no one who reads the essay, rebranded itself under new management last fall). The story of how the sanctuary came to be starts out clear, but gets rocky, as it can only be told through rumors, dropped calls, misunderstandings, and finally, photos from a police report.

Gerard talks to everyone orbiting the sanctuary she can, piecing together a messy narrative from new and old employees, news articles, and Dewar’s advertisements, family members, even a guitarist named Jimbo. Eventually, she gets to the founder of the sanctuary, Ralph Heath, a Miss Havisham of a man, who spends most of his time tending to his “private collection” a warehouse of birds owned by his adult children.

But Ralph won’t, and it seems, can’t, give her the answers she’s looking for. And here is the power of the collection: Gerard is constantly searching without truly knowing, a thread that unifies the entire collection.

“BFF,” the opening essay, is about her first best friend, about finding and losing her slowly, clinging even after they’d grown apart: “I pretended we were still best friends when we got our tattoos.”

She writes about the unraveling of that intimacy as a person who has hurt and been hurt, in memories and fragments: “Lies I know you told me / Lies I heard you tell yourself / Lies I told you” – but never manages to pinpoint exactly what drove the friends apart. Of course, it’s impossible. We become blind, numb to so many things without realizing they’ve faded away, and we’re left only with the aching memories, the sting of what’s missing. When Gerard writes, “You’re the only woman I’ve loved this way: enough to want to hurt you.” you believe her — and it stings you, too.

She’s writing toward our trust, and she earns it quickly, allowing her to flip seamlessly between the Florida that she’s lived and the Florida that she’s seen.

“The Mayor of Williams Park” takes a winding look at the homeless of Pinellas County, FL with a focus on G.W. Rolle, the formerly homeless minister of the Missio Dei church, which holds weekend breakfasts. Focusing on Rolle, on his mission and his struggles, allows Gerard the space to look at homelessness from up close and from far away. She does not approach the topic as a solvable problem (which would be reductive), instead, giving it space to breathe and be, which makes the reader experience enough perspectives to feel as helpless and conflicted as she seems to be.

When she focuses on herself, Gerard still manages to write toward something universal. “Records” is an examination of her last year of high school, budding adulthood, and consent that hit so close to home I felt bruised. And ”Before: An Inventory” is a poem that should not, by logic, be closing an essay collection, but manages to pull together a life in scraps. Always searching, always learning, rarely knowing a single thing for sure.

In the book’s longer essays, Gerard reveals fewer personal details, but they read as incredibly intimate. Going Diamond, a piece about Amway and the lifestyle it promises, first published in Granta last fall, feels more ominous now that Betsy DeVos has been confirmed the Secretary of Education. Gerard’s parents, luckily, broke even in their Amway days, but the stress of it lingers throughout history of Amway, in the background of gated-community open houses. There might never be enough, and it could be lost at any second.

The essay with the widest scope was also my favorite. “Mother-Father God,” is a meditation on the history of Christian Science and her parents’ path to sobriety and the Unity-Clearwater Church, as much as it’s about faith and doubt, as much as it’s a loving portrait of her mother.

She writes about her mother’s first husband, and how she realized, “Bob could kill her body, but he couldn’t kill her; he could physically control her, but he couldn’t control her mind.” This led her mother to leave, to drink to ease the loneliness, to meet her father in a bar, pining for her ex-boyfriend. The two of them get sober separately, then together, finding the New Thought Movement, and starting a family and a life together.

Gerard’s life, though her family spent less and less time in church as she got older, was shaped by the way the church teaches its followers to think positively, as negative thoughts can manifest themselves as illness or prophecy. “Despite all the time that had passed…positivity wasn’t doctrine; it was truth.”

The effect this has on her marriage to a lapsed Catholic with a tendency to think negatively is one that she has trouble quantifying. It isn’t until she looks at the fundamental differences in the religions they were raised with does she realize, “For me it was beyond his pessimistic tendencies and my optimistic one — in articulating his pessimism, he was sharing it with me, and in listening was committing the mortal sin of casting doubt.”

“Doubt to me was equivalent to mortal sin: to cast doubt upon a hope was to do away with all possibility of hope’s fulfillment, and would doom me to a life of hopelessness.“

Gerard’s mother became an advocate for victims of domestic violence in the local police force and the director of a domestic violence shelter. She held NOW meetings in their house, attended church, kept fighting. She kept a prayer journal, where she wrote, “I find this mystery fascinating, how much I’m shaped by something I no longer wholly remember.“

But all of the effort could not stop the cycles of violence, it could only break a fraction of them, sometimes only for a few days. “My mom sought solace in her faith…but where was the solace for these women?”

There aren’t answers in Sunshine State. It is a book about the search rather than the discovery, leaving mindful space between the facts for all the things we cannot know.