A (Psychic) Portrait of The Artist: Looking at the Work of W.C. Bevan

14.01.14

The August I stayed with New York based artist W.C. Bevan, I had just gone through what I now half-jokingly have deemed my dark period. I was nineteen, broken-hearted and living on my own for the first time outside of college. My circumstances and delusionally high capacity for self-pity had allowed me to become more or less an irresponsible, depressed, drug-addled piece of shit for most of the summer. To put it crudely. I think I was operating under the twisted idea that this made me an Artist. When I arrived at W.C’s West Harlem street apartment, it immediately became clear that this was not the case.

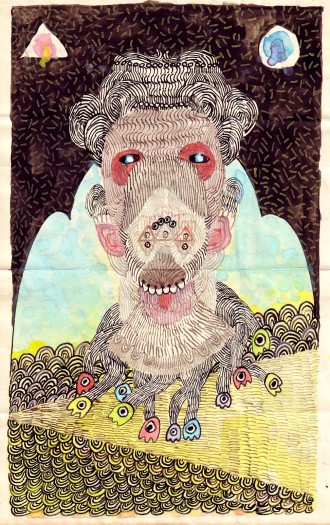

His room functioned as a hybrid studio/gallery. He was working on “psychic portraits,” a term I understood but then lacked the courage to ask about openly. They were bizarre, hypnotizing fountain pen drawings on old paper he routinely acquired from area craigslist sellers. The walls were adorned with older pieces: paintings, doodles, and even historical documents that seemed to chronicle not only past projects but “past lives.” Particularly memorable were the numerous paintings of pimps in bathtubs he attributed to “risky days. Tough milk.”

Since then, I have moved across the country and direct access to W.C. Bevan’s process and environment. For the most part, email correspondence is a lousy substitute for an up-close friendship, but it has given me the chance to ask my friend about his work directly.

While its subject matter ranges from abstract to cartoon to portrait, all of W.C. Bevan’s pieces share a sense of detail and portray a lively imagination remarking on the whimsical, magnificent oddity of life. Bevan describes his process as “sourly combating malfunctions with disembodied cartoons in psychic limbo. Then I walk around in circles until the fight begins again.”

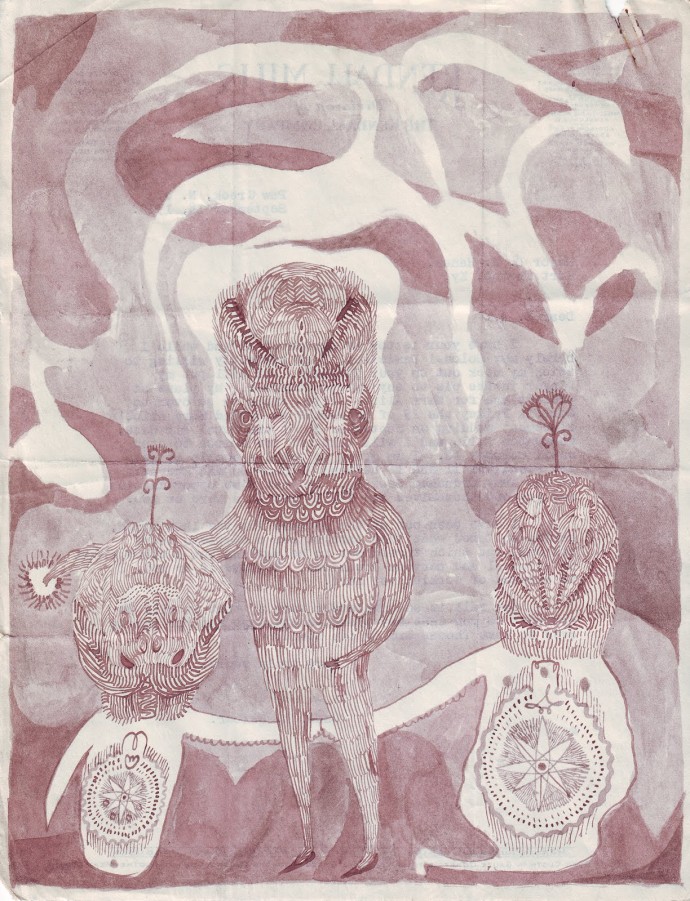

Each of W.C. Bevan’s psychic portraits is a unique creature, but they are united by characteristically meticulous repeated lines and unexpected shapes. Reiterated forms of lines, dots, and curves create a sense of ongoing movement and texture, while their variant quality evokes the tension between different forms and aspects of movement coexisting in a being and/or space.

Filled with parallel and echoed marks, these pictures ultimately seem to offer resolution rather than merely present an arresting instance of conflict. Bevan describes a psychic portrait as “something that happens after I get in trouble with a good friend.” And so I got my answer. Revisiting these pieces, I am particularly struck by their dynamism; how myriad forms converse and conflict within their borders and then, subsides or is subsumed and unified in aesthetic reverberation. Unlike the largely still, posed subjects of traditional portraiture, the forms within these portraits are part of an ongoing, perhaps-cyclical progression from dissonance to serenity and back again.

When they appear in groups, these creatures possess an endearing, anthropomorphic quality, reaching out thin, gentle, arms. “Magic Light” depicts interrelated beings, engaged playfully with each other and the viewer. While they are partially comprised of abstraction and their faces and bodies refuse to conform to those of figural human or even animal painting, the subjects of this portrait are not merely alive, but incredibly expressive.

There are times in my life when I want to make beautiful things and feel incredibly impeded. I have felt confused and frustrated trying to make my life into a beautiful life and perceived other peoples lives as beautiful without knowing why or how I could emulate that.

I once thought art was a kind of life, which I realize now wasn’t a life at all; if anything, it was a way of rejecting life: making life into a set of circumstances you can pit yourself against. I think a lot of people do that. I once thought that art was something you could fill a room with, and I loved that room, even though it was always someone else’s. It was an important room.

What I’ve learned is that the whole world is a room to fill. You can keep filling it, and emptying it, or rearranging what’s inside. You can spend your life doing that: infusing the world with each infinitely peculiar world you sense within yourself, and it will make you happy and terrible and tiny and huge over and over.

——————–