She’s Used to Feeling Strange: On Ottessa Moshfegh’s Homesick for Another World

11.05.17

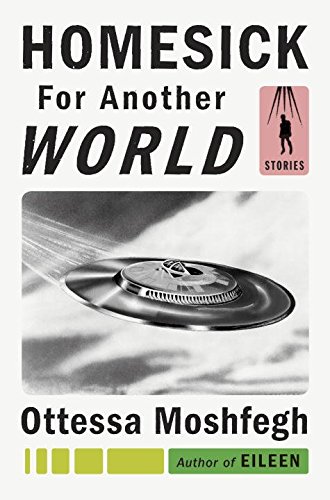

Homesick for Another World

Homesick for Another World

by Ottessa Moshfegh

Penguin Press

304 pp.

1.

I first heard of Ottessa Moshfegh’s work last year, when links to her now-infamous interview with The Guardian began popping up all over my Twitter feed. This was around the same time as her first novel, Eileen, was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. In the interview, she declared she’d written Eileen using a how-to manual called The 90-Day Novel. She’d begun writing it because she hoped to make a lot of money off of it, and that she wanted to be famous. She told The Guardian she didn’t want to “wait 30 years to be discovered . . . so I thought I’m going to do something bold. Because there are all these morons making millions of dollars, so why not me? I’m smart and talented and motivated and disciplined and . . . talented: did I say that already?” I found the whole interview refreshing, if slightly disconcerting. I’d been spending too much time reading about things Donald Trump had said about his own particular talents, and Moshfegh’s self-assessment had a whiff of the same self-aggrandizement. At the same time, I loved her honesty: what writer, at the beginning of their career, on some level, doesn’t wish they could make a lot of money and be famous? Moshfegh had swagger, and she was carrying herself like a big shot, saying things American writers don’t really say anymore about themselves. She was talking about herself like fucking Norman Mailer.

By the time I finished reading the interview I was grinning. I imagined all the head-shaking and finger-wagging she was going to provoke amongst the MFA / literary Twitter crowd. After all, when a writer who seems to have ambitions to being a serious artist—as Moshfegh’s first book, McGlue, an intensely literary novella that won the Fence Prize for Fiction, and her stories published in The Paris Review seemed to imply—declares that she wants to be famous and make a lot of money, she draws a line in the sand against preciousness. The defenders of preciousness—some of whom make their home in the world of academia—don’t like that sort of thing. I wondered if there’d be any backlash.

But then there was no backlash. Eileen was greeted with almost universal critical praise, and almost all of the writers I saw discussing her Guardian interview, and other, later, similar interviews, thought she was the coolest fucking thing since sliced fucking Wonder Bread. Literary grand-standing used to be par for the course, but in the last ten or so years, the only real public instances of literary braggadocio we’ve received have been the intermittent and oft-lampooned bloviations of reliable old Jonathan Franzen.

I think we can all agree we’re tired of making fun of Jonathan Franzen. It’s not even fun anymore.

So what made Moshfegh’s bit of self-aggrandizement different than Franzen’s? For one, I think nearly everyone, in terms of the little world of indie lit, was jazzed that in Ottessa Moshfegh was a writer who could jump from winning a $2,000 prize with a relatively obscure (to the non-indie lit world, at least) press like Fence to, with her very next book, being nominated for something international and starchy and prestigious and terribly important like the Man Booker Prize. In saying what she said in that interview with the Guardian (that she’d written Eileen as a fuck-you joke to the mainstream of the publishing world) Moshfegh was essentially shitting all over the Man Booker Prize’s selection of her novel, a move that was not all that different in spirit from Franzen’s refusal, with The Corrections, to have Oprah Winfrey’s sticker adorn his future book jackets. He made out just fine and so, it seems, has Moshfegh. Every single English-language publication with any readership whatsoever that covers books, including this one, has devoted space to her in the past year, and, it seems, almost all of them have been beguiled and mystified by both her prickly persona and the downright nastiness of the characters that populate her fictions. A recent profile in the Boston Globe ends thusly: “It feels strange, [Moshfegh] says, to be treated like an insider. But she’s used to feeling strange.”

So far, she’s the perfect of example of someone getting to have their cake and eat it too: a young, intensely literary writer, with the big advance and movie deal (Eileen was recently optioned by Fox Searchlight Pictures) To top it off, she seems so unimpressed by it all! Plus, she, like, actually made it! So cool!

2.

The world of Moshfegh’s fiction swarms with bizarre pleasures. It’s been there from the start. Here’s how the narrator of McGlue recalls losing his virginity: “The smell of it like cooking cabbage. What claims I’ve ever made to loving a woman scorned is just a half-truth. I love them most when they are suffering awful and full of wrath . . . My hands at their throats is a good one—all that soft, gristly stuff to squeeze.” In Eileen, the titular character muses that she believed her “first time would be by force. Of course I hoped to be raped by only the most soulful, gentle, handsome of men, somebody who was secretly in love with me . . .” and in the lead story of Homesick for another World, “Bettering Myself,” a teacher informs her favorite student she won’t “get fat from being ejaculated into.” At its best, Moshfegh’s relentless grotesqueries are the stuff of vicious, pitch-black comedy. One story’s protagonist, in a chapel, during his wife’s funeral service, experiences a moment of calm: “something seemed to break inside him. His breath caught. He choked and coughed. The wild thumping of his heart stopped. He belched loudly, from the depths of his gut, as though releasing some dark spirit that had been lodged down there his whole life.” A moment later he gets up, leaves the funeral service and, not to put too fine a point on it, goes to the restroom and takes a shit. It’s the kind of detail that, in the hands of nearly any other writer, would be grating in the extreme. His trip to the bathroom serves as a symbolic moment that is gracelessly compelling—yet still compelling nonetheless. Throughout the collection Moshfegh walks the line between the genuinely comic and the merely gross. At her very wicked best, as in the best stories of Flannery O’Connor and the coldest, most chilling moments of Dostoyevsky, the grotesque and the comic are cruelly, inextricably intertwined. Her characters are not merely fucked up—they like it that way.

At times this desire for self-destruction takes on a luridly sacred quality, as in when, in “Mr. Wu,” the protagonist alternates between obsession and revulsion for the cashier at an internet café. When the cashier finally rejects him—she, who he has alternately fantasized about and been disgusted by throughout the story—he sets the banner of a local supermarket on fire and walks home in the dark, “pausing now and then to raise his arms in victory.” Another story’s narrator declares that his bartender “could see that I wanted to be ruined. I wanted someone . . . to come and destroy me. ‘Murder me’ my eyes said to the woman.” Near the story’s end the unnamed protagonist barters his own clothes away in return for a shabby ottoman he knows is essentially worthless: “My future was at stake . . . The ottoman was a piece of shit, but that didn’t matter in the end.”

Moshfegh’s onslaught of the grotesque doesn’t always manage to move beyond itself. The collection’s final story, “A Better Place,” which can only be described as a kind of fucked-up fairy tale, follows a pair of children who “come from some other place . . . not like a real place on earth . . . but it certainly isn’t this place, here on earth, with all you silly people.” The only way to get back to the place is kill the right person. As in most classic fairy tales, the story’s logic is never fully explained. The story’s protagonist never questions the idea of murdering her way to paradise, and, like the writings of other fundamentalists, the result is suffocating, and the story never really gets enough air under its wings to fly. At their best, the stories in Homesick for Another World are bracingly strange and devastatingly funny. At their worst they drag themselves forward like the reanimated corpses of highly educated, beautiful people, never quite coming to life. I feel like this is largely a result of the repetition of Moshfegh’s subject matter. It’s not that more likeable characters are needed—far from it—it’s just that, repeated over nearly three hundred pages of fiction, even the most relentlessly repulsive and erratic characters acquire the same lifeless veneer of normalcy as most contemporary domestic fiction. To paraphrase Donald Hall: even in nonsense, sense.

3.

In a recent essay, Josephine Livingstone, writing in the New Republic, identifies Moshfegh’s style with the cold, ambivalent flatness of the writing of Tao Lin. Livingstone goes on to name Moshfegh and Lin (along with Nell Zink and Helen DeWitt, among others) as “Grandchildren of Camus”. While perhaps similar in tone, Moshfegh’s prose possesses a much greater sense of generosity of spirit than Lin’s. Camus’s characters lived in a world newly shorn of meaning, a world in which meaning had been hacked off and laid scattered all around in shards and fragments. The problem of Camus’s world was that the task of bringing those shards together seemed impossible, the weight of the task unbearable. In Moshfegh’s world, there are no shards—her characters have only the twin hands of excess and despair to guide them through the darkness.