3 Intersections of Heavy Metal and Romantic Art

17.02.14

I’ve always loved two things: Heavy metal and art history. Both topics, fine art and metal, are valid enough without the help of the other. Heavy metal does not need to make art cooler, and art has no business validating heavy metal.

But there’s an overlap where neither art nor heavy metal are trying to be something they are not: Album covers.

Whether created, commissioned, borrowed, stolen, or altered just enough to avoid copyright infringement, album covers are chosen to represent a record in its entirety. The visual history of heavy metal has an equal share of fine art replications, low brow illustrations, and under exposed photography. For as many album covers rely on landscapes of horror and grim depictions of dread, there just as many that turn to classical works. Paging through the catalog of famous and more obscure metal records can be a tour of western art’s most famous or obscure treasures. Aside from a flood of Gustave Dore lithographs and Casper David’s “Friedrich Monastery Graveyard in the Snow,” there are other selections that are thematically fitting or profane juxtapositions.

Heavy metal, much like art, is concerned with human emotion, existence, and the response to life’s grand narratives. So it’s natural that the grim and macabre reality of some of fine art’s most famous works are celebrated and obsessed over in heavy metal.

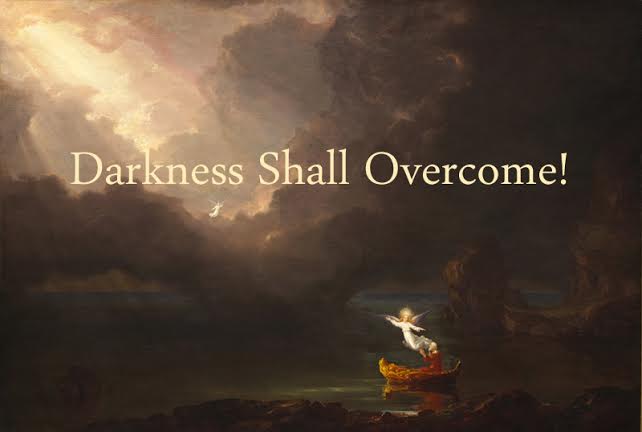

Thomas Cole – “The Voyage of Life” (1842) / Candlemass – Nightfall (1984)

Thomas Cole has become synonymous with the Hudson River School, which was a group of landscape painters who depicted the American wilderness as grand, untouched lands. The school would become intertwined with an academic movement that would later be known as Romanticism. Cole would also become famous for his large serial works — most notably “The Course of an Empire” and “The Voyage of Life.”

“The Voyage of Life” was a series of four paintings that portrays the journey from birth to death. These stages of life are depicted as the journey of a man walking along a growing river, with an angel at increasing intervals. Cole shows the man and the angel as small figures lost in an enormous landscape. The final panel, Old Age, sees the return of the heavenly figure waiting at the mouth of the ocean. The old man reaches up for comfort to a beam of other worldly light enveloped in a swirl of dark clouds.

The band Candlemass has become synonymous with epic doom. Candlemass took the sound of Black Sabbath and Pentagram and paired it with grand, classical themes. Candlemass’ pseudo operatic vocal style also helped cement them as a celebration of life and, more importantly, death.

Candlemass’ second record, Nightfall, saw the stark yet fluid transition of vocalist Johan Längqvist with Messiah Marcolin. Additionally, the band switched labels and hoped their vision of epic doom would be more commercially viable than their previous record Epicus Doomicus Metallicus. Nightfall would eventually become Candlemass’ most critically successful record and its single, “Bewitched,” has become one of Candlemass’ most talked about, and playfully joked about, music videos.

Candlemass’ inclusion of Cole’s final panel for “The Voyage of Life,” is not only painfully fitting for the album’s style but further explores the misunderstood connection of biblical subtext and heavy metal. Much like Sabbath did with their mortal fear and naivety of death, Candlemasses’ embrace of allegorical themes of life and death within the Christian tradition neither confirms nor denies religious affiliation, but rather celebrates the macabre in the narrative of life. Cole’s paintings, whose original popularity was with the growing protestant faith, now becomes cast as depicting the themes of doom, hopelessness, and the excitement of abandon.

Both Cole and Candlemass can be thought of as having the same general goal despite different means of reaching it. “The Voyage of Life,” which rests in a rotunda at the National Gallery in Washington D.C., is a tribute to living and the embrace of death. Nightfall has become a hallmark for doom and perhaps the most recognizable example of the epic subgenre. Both pieces beg the participants to experience the enormity of its themes and to show reverence to universal constants. Life is beautiful and death is inevitable. One just does it with low tuned guitars and the wail of mournful vocals.

Peter Nicolai Arbo – “Åsgårdsreien” (1872) / Bathory – Blood Fire Death (1988)

Though the 19th century in Western art is noted as the transition from the Neoclassical period into the Romantic, there were other things going on. These other things were the continuation of historical, landscape, battle, and traditional subject matter with schools dedicated to their execution. Bottom line: People did not stop painting ducks or rich people on horses.

Peter Nicolai Arbo was a Norwegian painter who spent the first half of his career painting historical Scandinavian battles, but later became known for his depictions of Nordic mythology. “Åsgårdsreien,” painted in 1872, combined Arbo’s craft of multiple figures embroiled in action with the grand scope of romantic landscapes. It would also become the face of viking metal.

Bathory was a Swedish black metal act lead by Thomas Börje Forsberg, known to many people as Quorthon. Bathory’s first three albums were seminal in the birth of the first wave of black metal’s sound, and chiseled it out as a raw continuation of the structure pioneered by Motorhead and Venom. Blood Fire Death did not dramatically change the sound of the previous record, Under the Sign of the Black Mark, but substituted some of the dark subject matter for historical and mythological references. The album would later be defined as the catalyst that moved first wave black metal to the now very misunderstood subgenre known as viking metal.

The Nordic mythos has become almost inseparable from heavy metal. Whether for the themes of glory within battle or a mythology that predates the dominant Christian institution, the myths of the Scandinavian people have been used to create songs that range from the celebratory to the downright silly. Bathory’s inclusion of Åsgårdsreien as the cover for Blood Fire Death is fitting as the album highlights a new direction for heavy metal. Compared to the goat-obsessed occultism of previous records, Bathory’s Nordic direction took a previously established sound and dressed it in something less threatening, and surprisingly more resonating.

Arbo’s “Åsgårdsreien” depicts The Wild Hunt, which is a North European myth of spectral riders crossing the sky in search of the dead and living. The folk myth was thought of as a harbinger of destruction, which is perhaps indicative of the turbulent existence of its believers. The Wild Hunt has since been adopted with different meanings, victims, and participants. The Norwegian, and perhaps most popular, version shows Odin tearing across the landscape on his eight-legged horse followed by a host of Valkyries. The myth finds romanticism in the dominance of ancient primal spirits who terrorize the weak and unbelieving. Parallels between the myth’s noisy riders and black metal’s dissonant structure have been drawn and discussed most notably by Michael Moynihan and Didrik Søderlind’s book Lords of Chaos. The Wild Hunt has become an icon for Norwegian mythology and now stands as an odd testament to heavy metal’s sometimes idiosyncratic obsessions.

Théodore Géricault – “The Raft of the Medusa” (1818) / Ahab – The Divinity of Oceans (2008)

Théodore Géricault would eventually become known for two works. One of them was his series of portraits depicting the mentally ill, and the other was his large tribute to the Medusa tragedy. Géricault’s life and legacy seems to have been built on the depiction of tragedy and ruin, and became one of the cornerstones in the growing Romantic movement. While Géricault’s subject matter is leagues darker than the Neoclassical themes before it, the sobering reality of his paintings, combined with traditional technique, brought dramatic focus to both the horror and beauty of current events.

Funeral doom is a style of heavy metal that took the slow structure of doom (much like Candlemass) and slowed it even further to the tempo of a dirge. From there, death growls were laid overtop, adding to a dismal style of monumental proportions. The style, popularized by bands like Skepticism, Thergothon, and Funeral, celebrated the fragility of life and the cold embrace of sorrow with anthems of gloom and ultimate doom. It was a style practiced by few but to the appreciation of, well, still a few. While the style’s innovators and largest names made records in the 90’s, funeral doom has seen some interesting innovations, Ahab in the mid 00’s being one of them.

“The Raft of the Medusa” became famous, or at least helped popularize Géricault, because of its political and scandalous nature. The historical tragedy occurred when the naval ship Medusa ran aground because of inexperienced officers, including a philosopher as the primary navigator. The wreck sent 147 of its crew onto a constructed raft to seek land 30 miles away. The tragedy occurred when 132 of these passengers died over the course of 15 days with its survivors supposedly resorting to cannibalism for survival. This grim sermon of human nature combined with a latent criticism of the then French government caught the interest of everyone. This is also the reason why Gericault’s painting made him a popular figure.

The Divinity of Oceans continues Ahab’s obsession with Moby Dick and the tragedies that helped to inspire Herman Melville’s opus. The band pays tribute to George Pollard, the real life captain who would later be immortalized in the character Captain Ahab, as well as Thomas Nickerson, who penned the first hand account of the Essex disaster.

The Divinity of Oceans contemplates the enormity of the ocean as well as its unsympathetic nature. One of the larger themes in the Divinity of Oceans is the acts of cannibalism that marked the Essex disaster, in which a vicious whale attack and subsequent marooning left 11 men dead. Ahab writes all of their lyrics in antiquated speech, which not only keeps character but also makes the death and gloom more timeless:

This world is turned upside down / By malisons of dire revenge / All fleshly means run aground / Hovering between life and death / All sense fade away / Darkness shall overcome! / Will you sink to ageless gloom! / Will you sigh out your soul!

Ahab’s choice of “The Raft of the Medusa” not only is fitting but draws parallels from two separate sea tragedies that are tied together with cannibalism. Géricault’s painting helped shift interest away from the airy reconstructions of neoclassicism and cement modern art in the unbiased viscera of the real world. The Divinity of Oceans continued funeral doom’s gloomy descent into depictions of literary horrors used as a platform to illustrate the complexity of human emotion in the face of tragedy. The premiere theme for both pieces is the will of man and the moment when that very thing is broken.