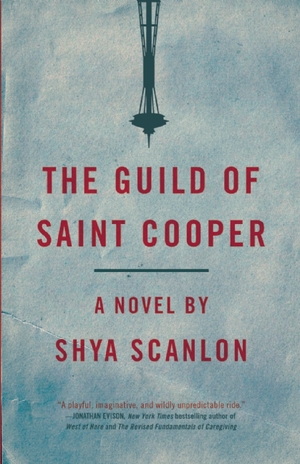

You’re Still Bound by Time: An Interview with Shya Scanlon

21.04.15

I pass Seattle’s downtown library on my way to work every morning. The library is an award-winning, somewhat controversial piece of architecture that I absolutely adore, even if it is not an ideal place to browse books. It’s just a pleasant place to be.

In The Guild of Saint Cooper, Shya Scanlon uses the library as the headquarters for a fringe-group in post-evacuation Seattle. He describes it as an “irregular glass and lattice frame zagged out of the pavement like a colossal glacier.”

That simple description has irrevocably changed how I see the structure. It’s hulking mass sits at the corner of 4th and Madison on one of the steepest descents into downtown. Now, I can’t help but imagine it slowly sliding toward Puget Sound, carving new canyons between the hotels and office buildings.

Having never lived in New York, I’m not used to walking around a city used as a backdrop for literary fiction.

It’s appropriate that Guild transformed Seattle for me as a reader, because that is the essential goal of its narrator: rewriting the city’s history, fundamentally rearranging its landscape.

I spoke with Scanlon about his book in advance of his arrival to Seattle as the second Writer-in-Residence for Authors, Publishers and Readers of Independent Literature (APRIL) 2015.

FANZINE: When APRIL was discussing our writer-in-residence candidates for this year, one of the arguments in your favor was that you’re a writer living in New York who is still writing about the West Coast. What about that setting is compelling to you?

FZ: The way I interpret the events in Guild is that Blake’s presence starts to alter the events somewhat beyond his control even, or as alternative timelines in a multiverse sort of situation. But there’s also textual evidence that this could just all be Blake’s escapist fantasy, the multiple drafts of a story he can’t quite figure out. While the timeline isn’t exactly linear, to say the least, the emotional arc does feel somewhat traditional in a satisfying way. How did you build/envision the novel’s structure?

SS: Whether or not the timeline of a story is linear, the reader—except in extreme examples like Cortazar’s Hopscotch—is going to experience it in a linear fashion. Meaning they are going to read through from the first page to (the author hopes) the last page. Even in the example of Hopscotch, you’re still reading one page to the next, even if you’re hopping around. You’re still reading one sentence to the next. One word to the next.

You’re still bound by time.

So in that way, the book, it’s characters, and particularly in the case of a first person narrator, is revealing itself to the reader linearly. I know this is rudimentary, but it’s actually a liberating thing to remind yourself of as a writer. I began experimenting with this in a series of linked stories a while back—my favorite structural departure was to let the story recede backward in time, from the central character’s “present tense,” via flashback, to an older period in time, and then to a period even farther back. Flashbacks are standard, of course, but what if the story ends without returning to the initial time period? What new pressures are put on the events in the character’s past that can have resonance for the reader, can inform the reader of something that feels important?

I was fascinated by the implications on character development, and brought those earlier experiments to bear on Guild. Of course, in Guild we do return to the present, but the movement backward in the former sections have had an effect on the present. In other words, the very process by which the narrative recedes into the past is itself forward-moving. It’s a back and forth motion that nonetheless has a goal and a shape. In the case of Guild, in fact, I hit on the structure of a tsunami. The tide flows some, then ebbs a great deal, and then returns with force destructive enough to upset the pre-existing conditions on land. You’re right to point out the trick: through it all, the narrator has to develop. I’m glad you felt that it wasn’t a complete failure!

As for the textual evidence you mention, yes, there is certainly something going on with Blake’s desire to escape those pre-existing conditions.

FZ: Yes! One of my favorite details was in the new timeline, Blake’s mother doesn’t get cancer. That was gut-wrenching for me. It’s like who hasn’t wanted to use their art to edit out something painful.

SS: I think all writers grapple with their art, which often feels just beyond our grasp. Escape can be a devious concept, too, because it’s freighted with curious negativity, which probably for me goes back to the Puritanical communitarianism I was a party to on both coasts of my upbringing. So I wanted to investigate that through this character, whose attachment to this mother (home) is an undercurrent to this motivation throughout the book in both positive and negative ways.

FZ: One of the reasons that I love this novel is because it seems to defy genre. People might call the inclusion of Agent Cooper fanfiction, but then there’s also the metanarrative, critique of humanity’s environmental degradation, and aliens abutting allusions to canonical literature. Did you write with genre in mind? Or how do you feel about genre in general?

In a recent posted over at Electric Lit, Lincoln Michel made the observation that the fracas over genre in The Buried Giant (Ishiguro’s public expression of anxiety and Le Guin’s subsequent public taking-him-to-task) seems almost quaint. He points out, rightly I believe, that instead pointing to any real raging debate, the exchange showed their age. I believe this is more or less true. At least, it’s becoming true.

It’s definitely true of my own aesthetic preferences and practice. Post-genre, I guess you’d have to call it. Or if that sounds too snobby, you could pull from a host of appellations that can’t seem to find popular footing: slipstream (too weird?), new wave fabulism (too ornate?), speculative (too speculative?).

Authors have undoubtedly always read (and more recently, watched/gamed) more omnivorously than their output would suggest. I think what my generation of writers have in common is a greater willingness to incorporate a broad range of influences into our work. Like, you know, Twin Peaks.

FZ: Why Twin Peaks?

SS: In a recent interview, Lorrie Moore noted the resurgent trend of having collected stories linked either explicitly by characters and setting or by theme—at any rate, intentionally. Running counter to this approach, she stood by her collection—I believe it was Bark—as simply a document of the fiction she’d written during a particular period of time. This stood out to me because my work (though I’ve written a linked collection, see above) operates similarly.

I do of course choose what I’m going to write about—at least, decisions I make early on set a narrative in motion—but a book length project requires years of commitment, and during that time I prefer to let the book collect, reflect, refract the various influences and experiences I encounter along the way. Much like Moore’s collection, in other words, my novels are very literally what I wrote during a certain period of time. My work has always been this way, but with the Guild I opened the aperture a bit wider. The result is a book that operates (somewhat) like a novel, but that is a record of my interests and anxieties from roughly 2009 through 2013.

Which is to say that to answer this question honestly is to look at that period of my life as much as to look within the book a la New Criticism. And in my life during this time, I was growing old enough to look back fondly at my youth. To reminisce in a pretty hardcore, disruptive way. And though I don’t think I can make a better case for my fascination with Twin Peaks than I did in the essay I published to kick off the Twin Peaks Project, I can say that the show and my rewatching of it bullied its way into my book through that aperture I mentioned by virtue of the impact it had made on me during the time of life I was so captured by.

Twin Peaks was a foundational show for me. It was my first experience with narrative that doesn’t restrict itself in register. It was comedic, it was serious, it was scary, it was goofy, it was dramatic—it was self-aware but nonetheless gave itself over entirely to the action. It’s a way I always try to write, and I’m not often successful. It’s difficult, for instance, to offer up humor in a scene that has to function dramatically. Many readers either don’t catch the humor, or do but think there should be more of it—that it should be the purpose of any scene it appears in.

Lorrie Moore does this better than most; another master is Tom Drury. I find myself imitating both of these authors on a scene level, trying to get at those moments where many moods are in operation concurrently. It’s what made Twin Peaks, despite its obvious flights into genre, so lifelike for me. Clearly the inclusion is in no small part homage.

I made no attempt to disguise my self-insertion with Blake—the mopey, conflicted, indecisive author lacking motivation to participate in the world around him—but there’s a lot of me in the Russell Jonskin character as well—the relatively unselfconscious braggart who wants to run with ideas he must ultimately know are going to strike many as absurd. His are slightly more ambitious, of course: he wants to rewrite the history of a city to include Dale Cooper. I just want to rewrite my novel to include him.

——————–