Yeah Right: A Brief History of Skateploitation Cinema

20.03.08

Detractors of the filmmaker Gus Van Sant often cite the prurient approach he takes to his pet subject, teen angst. And indeed in Van Sant’s new film, Paranoid Park, a high school skateboarder struggles with, among other things, his sexuality. But the flesh of newcomer Gabe Nevins (whom Van Sant cast via MySpace) isn’t the only thing being leered at. Van Sant also exploits skateboarding.

Detractors of the filmmaker Gus Van Sant often cite the prurient approach he takes to his pet subject, teen angst. And indeed in Van Sant’s new film, Paranoid Park, a high school skateboarder struggles with, among other things, his sexuality. But the flesh of newcomer Gabe Nevins (whom Van Sant cast via MySpace) isn’t the only thing being leered at. Van Sant also exploits skateboarding.

When Van Sant was interviewed recently by Blake Nelson, the author of the YA novel on which the film is based, Nelson asked the director whether he felt any kinship with the sport. “I had been a skateboarder in the ’60s, which was a long time ago, but I didn’t think that it was so much different,” he said, adding that in 1978 he worked on a movie where he “met the skaters of that time.”

Van Sant’s comments were doubly illuminating. First, few things will so readily invite derision from a skater as the old timer who brags about how he used to rip. More tellingly, the 1978 picture to which he refers—a PG-rated vehicle for Tiger Beat pin-up Leif Garrett called Skateboard: The Movie (That Defies Gravity)—was one of Hollywood’s pioneering attempts to turn a fast buck off what was then an emerging subculture. In a presumably unwitting ironic twist, the plot concerns a combovered codger manipulating a trio of skaters for profit.

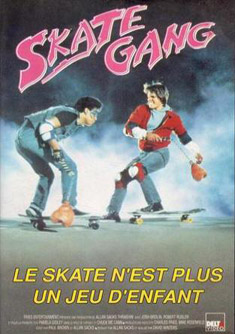

In the decades since, the fortunes of skateploitation cinema have intermittently risen and fallen, much like the inconsistent popularity of the sport itself. The 1980s were the golden years, yielding a pair of fishtail classics in Thrashin’ and Gleaming the Cube (starring Josh Brolin and Christian Slater, respectively). That era also gave us Robert Zemeckis’s nostalgic Back to the Future trilogy, which smoothed over skating’s punk edges by casting a lead, Michael J. Fox, better known for playing a Republican on TV. In Zemeckis’s vision of 2015, presented in Back to the Future II and III, children ride floating “hoverboards”—eliminating the possibility that skaters will do grinds, the set of tricks that tends to cause the most property damage.

In the decades since, the fortunes of skateploitation cinema have intermittently risen and fallen, much like the inconsistent popularity of the sport itself. The 1980s were the golden years, yielding a pair of fishtail classics in Thrashin’ and Gleaming the Cube (starring Josh Brolin and Christian Slater, respectively). That era also gave us Robert Zemeckis’s nostalgic Back to the Future trilogy, which smoothed over skating’s punk edges by casting a lead, Michael J. Fox, better known for playing a Republican on TV. In Zemeckis’s vision of 2015, presented in Back to the Future II and III, children ride floating “hoverboards”—eliminating the possibility that skaters will do grinds, the set of tricks that tends to cause the most property damage.

Then studios lost interest in the genre in the early 1990s, when skating died out and went underground. The only skateploitation film of note to be released during the Clinton administration was the Van Sant-produced, Larry Clark-directed indie shocker, Kids (1995). As with Clark’s follow-up, Wassup Rockers (2005), Kids deserves credit for portraying its picked-off-the-streets skaters in their natural element—getting high, running their mouths, and above all studying skate videos.

Thirteen years after Kids, skateboarding’s popularity is at an all-time high, driven by hip-hop and by Tony Hawk, the veteran X-Games champion determined to extend his brand as indiscriminately as Martha Stewart and Oprah. Skateploitation, as a corollary effect, is also undergoing a renaissance. It is discernible in fashion (see the ubiquitous hoodie), the Avril Lavigne discography, and MTV’s Life of Ryan and Rob and Big—an odious pair of reality shows about pro skaters. Skateploitation is also apparent in Catherine Hardwicke’s critically acclaimed Lords of Dogtown (2005), a superfluous dramatization of Stacy Peralta’s 2001 documentary, Dogtown and Z-Boys, the definitive account of 1970s Southern California surf style.

Thirteen years after Kids, skateboarding’s popularity is at an all-time high, driven by hip-hop and by Tony Hawk, the veteran X-Games champion determined to extend his brand as indiscriminately as Martha Stewart and Oprah. Skateploitation, as a corollary effect, is also undergoing a renaissance. It is discernible in fashion (see the ubiquitous hoodie), the Avril Lavigne discography, and MTV’s Life of Ryan and Rob and Big—an odious pair of reality shows about pro skaters. Skateploitation is also apparent in Catherine Hardwicke’s critically acclaimed Lords of Dogtown (2005), a superfluous dramatization of Stacy Peralta’s 2001 documentary, Dogtown and Z-Boys, the definitive account of 1970s Southern California surf style.

Paranoid Park stands out in the midst of this skateploitation revival, thanks to a unique sound design and arthouse cinematography (shot by Christopher Doyle, among others). And yet the slow motion effects so many reviewers have praised are largely an anomaly in the traditional skate video, where the difficulty of a trick cannot be appreciated unless it is seen in real time. More significantly, Paranoid Park’s eponymous “Westside” is built on a heap of juvenile delinquency clichés—which are all the more grating because they’re at odds with the true story behind the construction of Burnside, the downtown Portland skate mecca where these sequences were shot. (Skaters designed and illegally poured the concrete bowls themselves underneath a highway overpass, and eventually, when the success of the park helped spur an economic revival in the neighborhood, the city legitimized it.)

The joke is that with untold skate videos readily available on the internet—both home made and professional—skateploitation movies such as Paranoid Park are more obsolete than ever. As far as skaters are concerned—and as more cinephiles ought to be—skate videos have been rendering their mainstream imitators artistically unnecessary since the mid 1980s. That was when Peralta, the ex Z-Boy, began directing his Bones Brigade series. “I don’t feel like I came into my own until I was behind the scenes,” said Peralta, who saw the medium’s potential to make converts. “Kids that weren’t into skateboarding could actually see a video rather than a magazine and go, wow, so that’s how they do it.”

The joke is that with untold skate videos readily available on the internet—both home made and professional—skateploitation movies such as Paranoid Park are more obsolete than ever. As far as skaters are concerned—and as more cinephiles ought to be—skate videos have been rendering their mainstream imitators artistically unnecessary since the mid 1980s. That was when Peralta, the ex Z-Boy, began directing his Bones Brigade series. “I don’t feel like I came into my own until I was behind the scenes,” said Peralta, who saw the medium’s potential to make converts. “Kids that weren’t into skateboarding could actually see a video rather than a magazine and go, wow, so that’s how they do it.”

The Peralta oeuvre was as instructive about attitude as it was about the finer technical points. The Bones videos often began with skits in which Peralta himself would destroy a television after listening to yet another newscaster buffoon inaccurately characterize his sport. In 1987’s The Search for Animal Chin—Peralta’s masterpiece for its oft-imitated San Francisco hill bombing passage—the Bones Brigade parodically reenacts one of skateploitation’s most nonsensical scenes, cutting off the roof of a car with a jigsaw. “Now we’re just like the guys in Thrashin’,” one them says. “Real great.” Peralta is the undisputed O.G. practitioner of the first generation, but his videos relied too heavily on traditional elements such as plot and character. It took 1989’s seminal Rubbish Heap (recently reissued as part of a deluxe box set) to liberate the genre from these conventions.

Rubbish Heap, made on what looks like the poorest quality VHS stock available, was directed by a then-unknown skate rat named Spike Jonze. Eschewing the egotistical personalities, glossy logos, new wave soundtracks, and narrative continuity that marked Peralta’s era, Jonze established the verité template on which most contemporary skateboard videos are based. As Kids would do five years later for the non-initiates, Rubbish Heap showed skaters being themselves—committing antics such as focusing their boards (breaking them in half by stomping on their middle). Rubbish Heap was also the first video to elevate the slam (the term for when a skater hits the ground after a failed maneuver), granting the spectacular wipeout as much respect as the gracefully executed trick, and thus paving the way for the Jackass movement.

Jonze has gone on to have an eccentric career in feature films with Being John Malkovich, Adaptation, and the upcoming Where The Wild Things Are (not to mention his role as a Gulf War soldier in Three Kings). But in the shadow of these big productions he has continued to set the artistic standard for skate videos with Goldfish (1994), Mouse (1997), Yeah Right! (2003) and Hot Chocolate (2004). As part owner of Crailtap, the company that sponsors the Girl/Chocolate/Lakai teams who star in his videos, Jonze has a simple formula for success. He combines stylish skating with an imaginative sense of humor, as in this clip from Yeah Right!, in which actor Owen Wilson pretends to be a lazy, trash-talking pro (when Wilson appears to land a noseblunt slide on a rail, it’s actually Eric Koston in a blond wig). Fully Flared (2007), Jonze’s most recent four-wheeled opus—co-directed with long-time collaborators Ty Evans and Cory Weincheque—is widely considered the sickest skate video in a decade because it shows guys doing flip-in/flip-out tricks, done at improbable speeds, that the average skater couldn’t handle stationary on flat ground. One reason that Kids remains the least egregious of all skateploitation pictures is that director Larry Clark recognizes the preeminence of this parallel genre, and he acknowledges Jonze’s place within it. In a lengthy scene halfway through Kids, the skaters smoke up around a small TV that’s playing Jonze’s and Karol Winthrop’s revolutionary Video Days (1991).

Jonze has gone on to have an eccentric career in feature films with Being John Malkovich, Adaptation, and the upcoming Where The Wild Things Are (not to mention his role as a Gulf War soldier in Three Kings). But in the shadow of these big productions he has continued to set the artistic standard for skate videos with Goldfish (1994), Mouse (1997), Yeah Right! (2003) and Hot Chocolate (2004). As part owner of Crailtap, the company that sponsors the Girl/Chocolate/Lakai teams who star in his videos, Jonze has a simple formula for success. He combines stylish skating with an imaginative sense of humor, as in this clip from Yeah Right!, in which actor Owen Wilson pretends to be a lazy, trash-talking pro (when Wilson appears to land a noseblunt slide on a rail, it’s actually Eric Koston in a blond wig). Fully Flared (2007), Jonze’s most recent four-wheeled opus—co-directed with long-time collaborators Ty Evans and Cory Weincheque—is widely considered the sickest skate video in a decade because it shows guys doing flip-in/flip-out tricks, done at improbable speeds, that the average skater couldn’t handle stationary on flat ground. One reason that Kids remains the least egregious of all skateploitation pictures is that director Larry Clark recognizes the preeminence of this parallel genre, and he acknowledges Jonze’s place within it. In a lengthy scene halfway through Kids, the skaters smoke up around a small TV that’s playing Jonze’s and Karol Winthrop’s revolutionary Video Days (1991).

It is hardly a coincidence that Video Days opens with Mark Gonzales slamming from an epic staircase (“Gonz is the bomb,” you can hear Kids’ protagonist utter in the background). Clark understands that overcoming fear is essential to skateboarding. This isn’t a matter of machismo so much as physics. As Ben Davidson wrote more than thirty years ago in The Skateboard Book, “Cuts, bruises, broken teeth, and concussions aren’t a rarity, and unless you’re just going to cruise slowly up and down your block in straight lines, a casual attitude toward the sport is self-destructive.” It is understandable that in Paranoid Park, Van Sant’s teenager feels paralyzed by the things that scare him—girls, boys, his parents, better skaters. But, repeatedly, he can’t summon the courage to drop in at the skatepark and risk the pain and humiliation of slamming. In this way he’s a lot like his director—someone from the outside looking in.