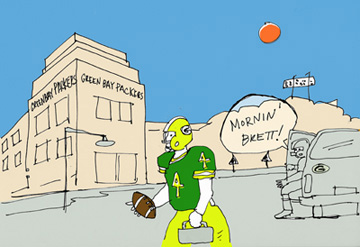

Mississippi Dusk: Brett Favre Retires

08.03.08

It’s fitting that my father officially announced his retirement the same day that Brett Favre did, because for at least five years my family has been wondering who would hang it up first. I immediately called my dad when the Favre news broke, because I wanted to ask him if he had given notice yet, so I could write about it, given the other big news of the day. “What news?” he asked. He hadn’t yet heard, since he had been in meetings all morning.

It’s fitting that my father officially announced his retirement the same day that Brett Favre did, because for at least five years my family has been wondering who would hang it up first. I immediately called my dad when the Favre news broke, because I wanted to ask him if he had given notice yet, so I could write about it, given the other big news of the day. “What news?” he asked. He hadn’t yet heard, since he had been in meetings all morning.

This is a sports column, so I’m not going to write about how my dad worked in Research & Development at Kraft Foods for 34 years to put food on our table, and Lunchables on yours. Millions of Americans go to work and come home for the better part of their lives, and then finally reach a day when, hopefully, they can close that door and open a new one. Brett Favre isn’t anything like most Americans in this regard. He could have retired ten years ago and still lived comfortably on the millions of dollars he’d earned, both as quarterback for the Green Bay Packers, and in endorsements. And more words were written about Favre’s decision day than will be written about the entire lives of most persons. That may seem unfair to the doctors, teachers, soldiers, firefighters, factory workers, and other ordinary laborers out there, but no one buys tickets to watch them work. For those of us who understand athletics as entertainment, Brett Favre was a transcendent entertainer, a supremely talented professional who somehow managed to perform the way the way the teacher, and the soldier, and the firefighter, and the factory worker imagines he or she would perform were he or she a quarterback. If we watched a Marlon Brando movie not just to enjoy a movie, but also to see Brando, or went to a museum not just to see art but to see Leonardo, then we turned on our TVs on Sunday not just to watch football, but to watch Favre.

It is this aspect of Favre’s appeal that has been played up, torn down, and lampooned, but nevertheless it was the quarterback’s unbridled enthusiasm that made him beloved. Few of us, given the opportunity to earn millions as athletes, can imagine allowing ourselves to be shot with steroids in the buttocks, or choking our coach, or spitting on a fan who paid good money to watch us play. But we can all imagine throwing our arms up in the air, hoisting our teammates, laughing, joking, crying, and enjoying football the way Favre did in Green Bay for 17 years. Brett Favre made watching sports fun, which is as it should be.

Just like your average Joe knows that Superman came from Krypton and grew up in Kansas, most casual sports fans are familiar with at least some details in the Favre mythology: The son of a football coach, he grew up near coastal Mississippi, and played in college at Southern Miss. He lost several feet of intestine after a car accident in college, and was later diagnosed with the same degenerative hip injury that ended Bo Jackson’s career. In 1991, Favre was drafted by the Atlanta Falcons, where he rode the pine for a year as Jerry Glanville’s favorite whipping boy. In 1992, a seemingly crazy general manager named Ron Wolf traded a first round draft pick for the second-year pro, which brought Number Four to Green Bay.

The rest is history, right? Not quite. Packer Nation was not always 100 percent behind its new golden boy. Favre’s first regular season completion—thrown in mop-up duty during a Tampa Bay-delivered ass-stomping—was laughable. Flushed from the pocket, he tossed a pass directly into the path of a Buccaneer defender, who swatted it back into Brett’s arms before tackling him for a five-yard loss, giving Favre the bizarre distinction of catching his first professional completion. Although he delivered three straight 9-7 seasons, Favre played unevenly during those early years, often enduring the wrath of Mike Holmgren and the scorn of frustrated fans. With two promising backups in Ty Detmer and Mark Brunell, Favre had to fight hard to keep his job.

The rest is history, right? Not quite. Packer Nation was not always 100 percent behind its new golden boy. Favre’s first regular season completion—thrown in mop-up duty during a Tampa Bay-delivered ass-stomping—was laughable. Flushed from the pocket, he tossed a pass directly into the path of a Buccaneer defender, who swatted it back into Brett’s arms before tackling him for a five-yard loss, giving Favre the bizarre distinction of catching his first professional completion. Although he delivered three straight 9-7 seasons, Favre played unevenly during those early years, often enduring the wrath of Mike Holmgren and the scorn of frustrated fans. With two promising backups in Ty Detmer and Mark Brunell, Favre had to fight hard to keep his job.

This is what fans, and a presumably conflicted Holmgren, came to love about Favre: His fight. He could be maddeningly reckless at times, but his willingness to risk an interception—and his ability if he threw one to shrug it off—makes for useful symbolism in the lives of mere mortals. His willingness to fail is probably his most noble quality. We all come to those moments when we can take a shot, and perhaps we score, or perhaps the ball is taken away from us. The truly regretful among us know that they did not take that shot. Those of us who failed, who fell down, know we can get the ball back. Could there be a better lesson drawn from 288 career interceptions? Brett Favre, touchdown king and interception king, Super Bowl champion and third string scrub, teaches us to try.

It’s fitting that a man who never phoned it in on the job is retiring because he can no longer honestly dedicate himself 100 percent to his job. No doubt, many fans think this is unfair. Coming off a 13-3 season, a hairsbreadth from the Super Bowl, how could Favre quit now? But his decision is more than fair—to play one more year without the burning desire to attain excellence would cheat millions of Cheeseheads. It’s painful that his final play was a game-turning interception, but how much more painful would it be to see Favre back on the bench in 2008, or dragged off the field by a physician? Or—perish the thought—spending his final season in Viking purple or Dolphin teal?

In the post-Lombardi ‘70s and ‘80s, the Green Bay Packers were a horseshit franchise, a perennially terrible team whose very existence in modern sports seemed like an accident of luck, or a sick joke. Since Favre started his first game in 1992, the Packers have gone an NFL best 160-93, with seven division titles, eleven playoff berths, and one Super Bowl title. And they’ve had the same man under center for 253 games. Brett Favre has earned his place in football lore. And, like millions of hard workers, including my father, he’s earned his rest. Let’s give him that in return.