Why Normal Has Failed To Occur: On Monster Portraits

01.05.18

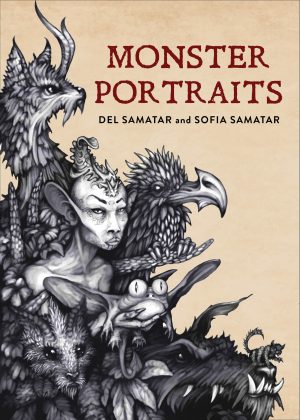

Monster Portraits

by Del Samatar and Sofia Samatar

Rose Metal Press

84 pp. / $14.95

Monsters are hybrids. Many scholars believe they’re a combination of our ancestors’ most common predators. Warning signals in our monkey brains morphed together when our evolved brains had the capacity for storytelling.

Del and Sofia Samatar’s Monster Portraits is a hybrid too: a mix of fiction, non-fiction, and art. The Samatars didn’t exactly know what they were creating when they started the project. The book was inspired by Del’s drawings, and the plan was for Sofia to write stories to accompany the images. But as their process continued, and as they thought more deeply about monsters, the book took a turn. It begins with a “we” going into the field to “study monsters in their environment.” But the monsters serve as a vehicle. The stories are mixed with research, found text, and autobiography that explore race, fear of the other, and fear of being the other.

There are certainly monsters in the book. A bristly, six-legged beast with heavy tusks and the brow of an overworked animal. A humanoid mantis whose wedding turns bloody. A manufactured nanny who’s gone subterranean after murdering a family. Even a sexy zebra. And each is intricately illustrated by Del Samatar. He’s created images that ask you to stay and explore.

But the writing is more compelling when we dip into research and real life. “The Search” is a beautiful collection of Google Scholar search results. Ambrose Pare’s illustrated On Monsters and Marvels is the center of “The Collector of Treasures,” where we learn Pare was hoping to discover “why normal has failed to occur.” Throughout the book, other voices speak, telling us “women were caused by error and “You are inferior as a Coloured.” Monsters are a mirror on our own fears and values, and this found text reveals our obsession with the normal and easily categorized. Even the notes at the end of the book are a fascinating read.

We get to the heart of the book when memory creeps in. Brother and sister watch Knight Rider, safe until they go to school and are asked “Are you black or white?” At a playground, another child tells the young narrator, “The dog bites black people.” The narrator fears for her father but doesn’t fully understand her own danger. After all, she’s the same child who tells her mother “I don’t like Nairobi,” because “there’s too many black people here.” The reasons we created monsters becomes more complicated.

Monster Portraits is strongest when the theory, image, and autobiography come together in one story. In “The Clan of the Claw”, our narrator meets with a creature named the Miuliu. The narrator’s “mixed blood roared like an April thaw,” and when her clan is mentioned, she imagines of “the clan of immigrants and hyphens.” She identifies with the creature whose “heart bore a pair of claws that were useful for nothing…but scratching at itself.” Here we see the trouble with normal. Where does a mixed-race child belong when a hybrid is a monster?

While the creatures in this book are inventive, the frame falls away quickly. The interviews with monstrous creatures are interrupted in favor of the thematic. The book reads more like a collection of poems than a work of fiction. Monster Portraits won’t offer you a beginning, middle, and end. It won’t offer you characters who resolve their conflicts. What it will offer is something less definable, more questions about ourselves than answers, and a good lesson in monster theory.