What’s So Funny About Peace, Love, and Kim Jong Il Bashing? An Interview With Bruce Cumings

31.03.07

University of Chicago history professor Bruce Cumings has written about the politics of both Koreas for over 25 years, most recently in North Korea: Another Country and Inventing the Axis of Evil. He has been outspoken on the need for normalization of U.S.-North Korean relations and a diplomatic solution to the nuclear stand off. Cumings’ work has also been critical of U.S. support for previous South Korean dictators, such as Park Chung Hee and Chun Doo Hwan, who came to power through military coups and used torture and assassination to silence critics and repress labor movements. In this interview he gives a perspective on North Korea not often heard in mainstream news coverage and describes his own experiences under South Korean dictatorships.

University of Chicago history professor Bruce Cumings has written about the politics of both Koreas for over 25 years, most recently in North Korea: Another Country and Inventing the Axis of Evil. He has been outspoken on the need for normalization of U.S.-North Korean relations and a diplomatic solution to the nuclear stand off. Cumings’ work has also been critical of U.S. support for previous South Korean dictators, such as Park Chung Hee and Chun Doo Hwan, who came to power through military coups and used torture and assassination to silence critics and repress labor movements. In this interview he gives a perspective on North Korea not often heard in mainstream news coverage and describes his own experiences under South Korean dictatorships.

FZ: While there has been a panicky tone to the U.S. media coverage of the North Korean nuclear test, I was surprised to hear from a friend who is living in Seoul that the reaction among South Koreans seems to be pretty casual. She said she would hardly know the test had occurred if it weren’t for CNN and the Armed Forces Radio Network. I wondered if you had any comments as to why South Koreans might not be as shocked or worried about the test as the U.S. seems to be?

BC: South Koreans have lived under the threat of North Korean invasion since about 1946 and with the possibility of weapons of mass destruction since the early 1960s. North Korea is widely known to have a large stock of chemical and possibly biological weapons and, of course, now it claims to have an atomic bomb.

Quite apart from the nuclear problem, North Korean missiles can hit anywhere in South Korea, including one of the many nuclear reactors that South Korea uses for electric generation and absolutely devastate the entire country. Furthermore, North Korea has several thousand artillery guns buried in the mountains north of Seoul that can wipe out the entire city and turn it into a sea of fire.

So when you know these things and you live with them then the fact that North Korea is going to get a nuclear weapon doesn’t make a whole lot of difference to you.

In addition there are many Korean nationalists of all stripes: left, right and middle, who think, “Well, sooner or later we’re going to unify with North Korea and guess what? We’ll be a nuclear power. The Japanese won’t be able to push us around and neither will China or the U.S,” and so on and so forth. It’s not surprising that South Korea would feel much less threatened than CNN pundits seem to feel about the North Korean nuclear program.

FZ: What’s the response from the South Korean government to the possibility of a preemptive strike against North Korea?

FZ: What’s the response from the South Korean government to the possibility of a preemptive strike against North Korea?

BC: I don’t think any responsible public official in the current administration of President Roh Moo Hyun has said that they would support an attack on Yongbyon. It wasn’t very well known at the time but back in 1994 Bill Clinton nearly carried out a preemptive strike against the North Korean nuclear facilities. Jimmy Carter flew to Pyongyong and intervened. He talked with Kim Il Sung and obtained a freeze on their nuclear facility, which was codified in the “October Framework Agreement” that kept North Korea’s plutonium facilities frozen for eight years.

At that point Kim Young Sam was president of South Korea and relations were very bad with the North. Kim Young Sam might well have supported a preemptive strike but what he’s said in retrospect, although Americans officials deny this, is that he wasn’t even consulted about it.

It raises an issue which Bush’s preemptive doctrine has raised in spades for Roh Moo Hyun: How could South Korea allow the United States to attack North Korea when South Korea would bear the brunt of the retaliation from the North? American officials including Rumsfeld and Cheney have said that this is too important of a question for us to give some sort of veto power to Seoul, and South Korea’s fear is that a war might develop without their assent. Adding to this problem is that when Rumsfeld moved 9,000 combat troops out of Korea to Iraq there were only bare levels of consultation with the South. Koreans have lived with our troops in their country since 1945 but always with the assumption that they were there to defend against North Korea.

When Rumsfeld began moving those troops around a kind of Pandora’s box of possibilities opened up and scared the hell out of Korean leaders. There are other flash points in East Asia, such as Taiwan. If China were to get into a war and the U.S. defended Taiwan, would the 30,000 troops in South Korea be used to fight there? In that case South Korea would be open to Chinese attacks to keep those troops from going to Taiwan.

In 2001 South Korean President Kim Dae Jung finally had Washington and Seoul moving in tandem with other allies to engage North Korea; to keep the nuclear facility at Yongbyon frozen and to indirectly buy out their medium and long-range missiles. I show my students the front page of the New York Times from October 2000 in which North Korea’s top general, who also runs the conglomerate that makes and sells North Korean missiles, came to visit Clinton. Even well informed people forget about the progress that was being made during that time because all of that diplomacy came to a stop when the 2000 election got held up on hanging chads. After Bush was declared winner by the Supreme Court, his people told Clinton that they didn’t want to go through with that deal and wouldn’t honor it and so on.

South Korean leaders were very happy about the policies of the late 1990s and when Bush stuck North Korea in the Axis of Evil it caused a deep estrangement—more so with Roh Moo Hyun than with Kim Dae Jung, who was president until 2002. Kim Dae Jung has always been a very pro-American person and believes deeply in this country’s democracy. Roh Moo Hyun, the current president, who was a protégé of Kim’s, had never been to the United States before he became president. He doesn’t speak any English. He’s much more of a native Korean and hasn’t liked what Bush has been doing one bit.

FZ: If North Korea were to use their nuclear weapons not as a negotiating tactic but in an actual attack, do you believe that South Korea would be the primary target? There’s a long history of animosity between Korea and Japan and conversely a long history of national unity between the two Koreas, which makes me wonder if Japan might be a more likely target.

BC: If a war were to break out and the South Korean army fought on the side of the United States, North Korea would have to hit South Korea. But you’re right that one of the most interesting secrets these days would be to know what North Korea’s targeting regimens are because for almost a decade now there has been a reconciliation between the North and South. Tens of thousands of South Koreans have been to the North and learned that they are cousins rather than evil people. This reconciliation comes at a time when Japan’s relations with both Koreas are at a real nadir.

North Korea and Japan have never had good relations and because Kim Jong Il admitted to abducting several Japanese citizens they’re now at an all time low. North Korea has over 100 medium range missiles that could hit every point in Japan. The missiles are mobile or hidden and very hard to take out. If a war were to develop, if there was a preemptive attack against North Korea it’s quite possible that North Korea would extend the war to Japan and spare as much as it could the South Korean civilian population in hopes that it would side with the North.

Anyone who imagines that a new Korean war would be anything but a complete disaster doesn’t know the situation. North Korea can inflict utter devastation on its neighbors even if it loses the war, which it would. Our war plans say that we need half a million troops in the Korean theater to defeat North Korea and even then it would take six months. North Korea has 15,000 national security and military facilities; it’s one of the most dug-in garrison states in world history with a tremendous capacity to demolish the northern region.

Just about every Democrat and many Republicans understand now that there is no military option on the Korean peninsula. Conversely, the North Koreans know that if they were to attack somebody—South Korea, Japan or the United States—that we would utterly destroy them. In 1995 Colin Powell said that if North Korea used one of its weapons of mass destruction we would turn it into a charcoal briquette. I don’t know how you can get any more blunt than that, but that’s exactly what would happen. North Korea has a return address and therefore if it were to use one of its nuclear weapons it would be the end of North Korea and the loss of millions of lives. The most important point about this nuclear program is that it can only be ended through negotiation.

FZ: Your essay in Inventing the Axis of Evil and your recent book North Korea: Another Country address a lot of the politics behind the U.S. selection of North Korea as a dangerous rogue nation. What do you see as some of the most glaring omissions and misperceptions in the U.S. media coverage of nuclear North Korea and U.S. involvement there?

FZ: Your essay in Inventing the Axis of Evil and your recent book North Korea: Another Country address a lot of the politics behind the U.S. selection of North Korea as a dangerous rogue nation. What do you see as some of the most glaring omissions and misperceptions in the U.S. media coverage of nuclear North Korea and U.S. involvement there?

BC: The North Korean regime is a repellent regime but what is missing is the history of our relations with North Korea. The Korean War is considered a forgotten war in this country but it has never officially ended. There was never a peace treaty, only an armistice and there is a long origin to the war that Americans know nothing about.

From the beginning and for the last 60 years North Korea has been lead by people who fought against the Japanese in a godforsaken, unforgiving guerilla war in Manchuria. Kim Il Sung made his name fighting against General Tojo in the mid-1930s. Had we known anything about that we might have been able to find a way to accommodate both North and South rather than divide the country. Instead, during the U.S. occupation of South Korea following World War II, we supported many people, including major military and police figures, who had collaborated with the Japanese. We punched into a political, cultural and historical thicket without knowing what we were doing and got ourselves into a major war five years later. It’s essentially the same thing that is happening in Iraq. It’s one of the myths and maladies of American leadership: that we’re going to be able to knock over the bad guys and a democracy will sprout soon after. Sixty-two years after we first sent combat soldiers to Korea, there are still 30,000 troops there. At some point you have to ask the question, “How long are we going to stay?” The Korean War was one of the most devastating in modern history and killed millions of people but solved nothing. We haven’t solved the problem that those combat troops went there to solve in 1945, which was Kim Il Sung.

Concerning our nuclear problems with North Korea, it’s important to understand that the U.S. was the first to install nuclear weapons on the Korean peninsula. We first put nuclear weapons into the South in 1958 and soon after we had hundreds of them. Because North Korea did not have the capability for nuclear retaliation, our war plans called for them to be used very early on in the event of a North Korean invasion unlike Europe, where if the Soviets and their allies invaded we were going to move back and back and back and not use nuclear weapons except as a last resort because they had them as well.

In 1991 George Bush, Sr. took our nuclear weapons out of South Korea because the military was moving towards precision-guided, high explosives that essentially could do the same thing without all the problems of using nukes. On any day of the week one of our Trident submarines can glide up to the North Korean coast and blast every city that they have. North Korea has been engaged in nuclear deterrence. It’s as simple as that.

I believe that they initially wanted to trade their nuclear weapons to the Clinton administration for normalization: to have our embassy in Pyongyang, to have security guarantees and a peace treaty on the Korean War. All of which was being negotiated in the 1990s. I believe that they didn’t want to be a nuclear power, but five or six years into the Bush administration, I’m afraid they made a decision to be one. In any case now that they’ve blown off a small nuclear weapon, it’s going to make it much, much harder to get them to give up their nuclear weapons and programs. That horse is out of the barn unfortunately and it’s going to be very hard to get it back in.

I watch CNN all the time and I’ve never once heard them say what our targeting practices are, or what our use of nuclear weapons would be in the event of a new Korean war, or mention the many decades we had nuclear weapons in South Korea. You just never get that! Instead you get a bunch of North Korean experts that I’ve never heard of and I’ve been in the field 30 years! They come on TV and usually one is representing some kind of Democratic Party point of view and another representing some kind of Republican point of view and they shout at each other, and it’s no wonder that the American people are not informed at all about what is going on.

When they run a clip on North Korea they almost always begin with goose-stepping soldiers marching through Pyongyang. You would think from this that North Koreans invented the goose-step or copied it from Hitler, when in fact Communist regimes going back to the Bolsheviks have done the goose-step. For once they might use an image from the multitude of films we have from NGOs that work in the North showing their employees working side by side with farmers to try to improve their crops. I’ve seen those films so why can’t CNN ever show them?

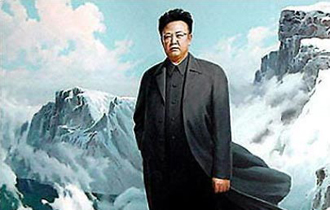

Last October the Kim Jong Il outfit was the most popular Halloween costume for kids. Kim Jong Il has become everybody’s piñata to throw whatever they want at him. So we’ve demonized him and made him into a horrible rogue dictator. He’s a dictator but he isn’t the madman that CNN often makes him out to be.

FZ: Guy Delisle’s non-fiction comic book Pyongyang was widely reviewed including in the magazine Foreign Affairs. In it, he describes a trip he took to North Korea while working for a French animation company; he depicts the NGOs distributing food in North Korea as helping to prop up the dictatorship. Clearly in your work there’s a compassion for people of both Koreas. How would you respond to the idea that just helping people to eat is just propping up the regime or the argument that the government would fall if people starved?

FZ: Guy Delisle’s non-fiction comic book Pyongyang was widely reviewed including in the magazine Foreign Affairs. In it, he describes a trip he took to North Korea while working for a French animation company; he depicts the NGOs distributing food in North Korea as helping to prop up the dictatorship. Clearly in your work there’s a compassion for people of both Koreas. How would you respond to the idea that just helping people to eat is just propping up the regime or the argument that the government would fall if people starved?

BC: It’s a fascinating little book and I actually blurbed it for the publisher, but the thing Delisle knows about is animation. Pyongyang has become the top location in the world for getting animated work done at a very cheap cost. They’re considered to be highly professional now and it’s one of the things North Korea makes foreign exchange on.

Guy Delisle is a fine person but he doesn’t know a lot about North Korea. The North Korean leadership is capable of starving millions of its people while staying in power and there’s no indication whatsoever that if we denied food to North Korea and lots of North Koreans died that this will be an effective way to overthrow the regime.

The American Friends Service Committee has done very good work delivering the agricultural aid to North Korea and I have served on their Asia panel for many years. When I talk to them and other NGO workers they are professional people that have devoted their lives to this work. They go around the world and they deal with regimes that they consider to be far worse than North Korea. What they say is that you help the people you can help. It isn’t propping up the regime to feed little children in an orphanage, or even if it is they need to be fed anyway.

I always ask myself, “Is something going to help the North Korean people or hurt them?” If you confront the regime directly you can bet it’s going to hurt them. There was a German human rights activist who tried to organize a boatload of people to get out of North Korea on the model of East Germany, which collapsed because so many East Germans fled to the West or to Czechoslovakia in 1989. His heart was in the right place but I knew that this would come to naught. Sure enough, about half the people on the boat were spies and a number of people got killed and that was the end of that escapade. So one has to take this very seriously and ask the costs and the benefits of bringing aid to people especially if there’s no chance that the regime might be disappearing in the next ten years.

I always tell my students to be comparative. When you study something in itself you often can’t figure it out. According to recent reports from CARITAS, the global Catholic social services organization which operates in North Korea, about 35 or 36 percent of the younger generation there are either wasted, malnourished, stunted, or sometimes all three. That’s truly terrible in a regime that used to feed all of its people very well. But they’re below the average level of the Philippines where decade in and decade out as well as in 2006 about 37 percent of children are wasted, malnourished or stunted. The Philippines were a U.S. colony from 1900-1946 and how do people feel about that? In India about 47 percent of all children under the age of five are considered malnourished. It doesn’t excuse North Korea in any way but it puts it in perspective. What’s truly inexcusable about North Korea is that they can feed everybody because it’s a regime that can penetrate down to every village.

In our country our viewpoint on these things in this country is totally skewed. I don’t in any way mean to excuse the North Korean regime but I do mean to say that there are ways we can influence the North Korean people in a positive manner by providing food and other kinds of aid.

FZ: In your book Korea’s Place in the Sun you mention in passing that in 1985 when future president Kim Dae Jung returned to South Korea you were part of a delegation, which included U.S. officials that escorted him on his return. You state that KCIA (the informal name for South Korea’s Agency for National Security Planning, also known as the ANSP, a spy agency modeled after the Soviet KGB) agents disrupted the delegation and abducted the South Korean leader. What was the U.S. response when Americans were attacked by South Korea’s intelligence agency?

BC: When the Chun Doo Hwan regime came to power in a coup in 1980 Kim Dae Jung was sentenced to death for his participation in the Kwangju rebellion, which he actually had very little to do with. The Carter administration and the incoming Reagan administration intervened to save his life. Kim Dae Jung was able to come to the United States as an exile and spent much of that time at Harvard writing a book.

He decided to return to South Korean in 1985 and because Filipino leader Benigno Aquino had recently been murdered on the tarmac at Manila airport after he returned from exile at Harvard, Kim Dae Jung got a delegation of people, including Robert White, who had been a U.S. ambassador in El Salvador, to protect him and draw attention to his return. It seemed unlikely the South Korean regime would murder Kim Dae Jung but you never know. Because I had known him since 1973 when I was a graduate student, I joined the delegation.

When we got off the 747 at the airport, a bunch of thugs in brown leather jackets separated us from Kim Dae Jung and his wife. They knocked us around and threw one of the women in our delegation to the floor. They took him away from us and we really didn’t know what had happened to him for about 24 hours. This caused quite a scandal and it was on the world news for a few days. The KCIA, I suppose, had certainly ordered this.

FZ: In your books you describe how during the time that you were teaching in South Korea student protests against the government were quite frequent and that some of your writings which were critical of the South Korean leadership were adopted by this movement. What was your role in all of this?

FZ: In your books you describe how during the time that you were teaching in South Korea student protests against the government were quite frequent and that some of your writings which were critical of the South Korean leadership were adopted by this movement. What was your role in all of this?

BC: When I arrived at Korea University in October of 1971 to conduct my dissertation research, there had been a lot of demonstrations on campus against the repressive government of Park Chung Hee, who had also come to power in a military coup. About a week after I moved into my office, General Park sent his tanks crashing through the gates of the university and blasted very virulent tear gas across the campus. I had to leave my office and clamor out of the backside of the university out on to the street to get the hell out of there. Of course, nobody knew who I was; I was just doing dissertation research and trying to keep my head down.

When my first book came out in 1981 on the origins of the Korean War, a lot of student militants read it and realized that they had been fed a lot of malarkey about the Korean War and the American military occupation from 1945 to 1948. Because I had been the first unofficial person to get access into the secret records of the American occupation I was able to cite really unimpeachable documentation, top-secret stuff that no Korean had read. The official language of that three year occupation was English and so Koreans just didn’t know what was going on. They knew what happened but they didn’t know why.

When President Chun Doo Hwan, who had declared martial law, banned my book it only made students want to read it more. It’s kind of like being on Nixon’s enemies list. Ever since then, right up until yesterday, I have Koreans coming to me asking me to sign one of my books saying that when they were students my work meant a lot to them. It’s very gratifying to me and it also represents a kind of a democratic impulse of opening archives and trying to tell the truth.

FZ: Yogi Berra, Richard Pryor and Nietzsche frequently come up in your writings. Is there are reason these non-Korean authorities frequently appear?

BC: A lot of scholars think I shouldn’t do that but I think these things are funny so I say them.