Review of Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season

27.04.07

During the 60th anniversary celebration of Jackie Robinson’s major league debut, his widow, Rachel, was presented the game’s Historic Achievement Award by Commissioner Bud Selig for her own contributions to the sport.

During the 60th anniversary celebration of Jackie Robinson’s major league debut, his widow, Rachel, was presented the game’s Historic Achievement Award by Commissioner Bud Selig for her own contributions to the sport.

She has carried on her late husband’s belief that, "A life is not important except for the impact it has on other lives." Having founded the Jackie Robinson Foundation in 1973, a year after her husband’s death at age 53, Rachel Robinson has seen more than $10 million in scholarships awarded to minority students.

Accepting the award, Mrs. Robinson said, "I was brought up in baseball in my adult life, and I’m very identified with the game and very proud with what we’ve done with the game."

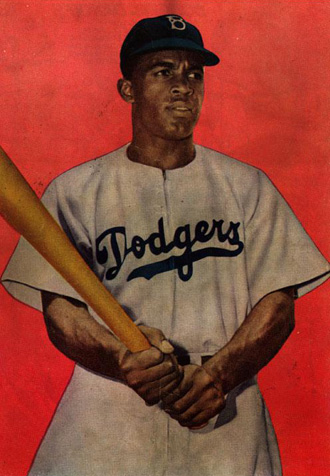

On April 15, 1947, when Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers and became the first African-American player in the major leagues, neither he or Rachel could have been sure that the game of baseball would become a lasting part of their lives.

As chronicled in Jonathan Eig’s carefully-researched Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season, 1947 was a thrilling but uncertain time for the Robinsons and other African Americans. Eig writes, "It was unclear if black Americans were on the brink of great gains or terrible troubles, but they were clearly on the brink."

Eig says that he tried not to imagine what Robinson experienced in 1947 but "worked at every turn to present verifiable facts." His interview subjects include Rachel Robinson (who allowed him access to a private scrapbook), numerous ballplayers of the era, writers, journalists, fans, and other observers of that historic season.

Noting that legend is often mistaken for fact where Robinson’s rookie season is concerned, Eig checked eyewitness accounts against newspaper reports of particular games. If doubt or contradiction exists regarding an occurrence from that season, he has been sure to point it out in Opening Day.

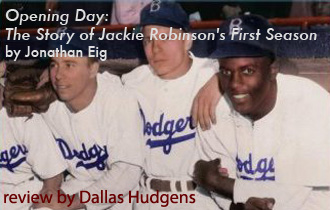

Watermelon pieces may not have been thrown at Robinson, and differing accounts make it difficult to know when, or in what city, teammate Pee Wee Reese placed his arm around Robinson to quiet a heckling crowd. But Eig verifies many other moments from the season. And while they may not all be powerful events on the surface, he recounts them in a textured and moving narrative that conveys both the personal experiences of Jackie and Rachel Robinson and the experience of the nation at large.

Watermelon pieces may not have been thrown at Robinson, and differing accounts make it difficult to know when, or in what city, teammate Pee Wee Reese placed his arm around Robinson to quiet a heckling crowd. But Eig verifies many other moments from the season. And while they may not all be powerful events on the surface, he recounts them in a textured and moving narrative that conveys both the personal experiences of Jackie and Rachel Robinson and the experience of the nation at large.

It might have appeared to white Americans that Robinson was being given a great opportunity in the major leagues. To him, it felt like his every action (large or small, on or off the field) was being scrutinized. He was on trial, and that feeling was shared by many of the African American fans who came to see him play during that first season.

Branch Rickey, the Dodgers’ owner who signed Robinson to a minor league contract in 1945, arranged a meeting with Brooklyn’s African American leaders to warn that the behavior of black fans could be the downfall of Robinson. As Eig points out, Rickey’s speech was "ill-mannered." But preachers and newspapers in the African American community relayed the message, calling on fans to be on their best behavior. The Amsterdam News in Harlem warned fans, "It will be well to remember that we are on the spot just as Jackie. We cannot afford to let him down!!!"

The New York Giants, National League rivals of the Dodgers, played their own home games at the Polo Grounds in Harlem. Opening Day reminds readers that Harlem became an early home to the civil rights

struggle around 1945. Leaders, activists, and entertainers had begun to call for the integration of white-owned businesses throughout New York City. World War II had ended, and black soldiers had fought for the sake of America. They deserved the opportunities that its democracy promised. Eig writes that the calls for equality that were rising from Harlem influenced Rickey’s signing of Robinson.

Meanwhile, in 1947, Rachel Robinson still had a difficult time finding a Manhattan cab driver who would stop and take her to Ebbets Field for opening day. At the stadium, her husband, who didn’t yet have a locker, dressed and hung his suit on a hook. Robinson later said that seeing his reflection in a clubhouse mirror wearing the Dodgers uniform made him feel like, "a stranger, or an uninvited guest."

After spending the first week of the season living in a hotel, the Robinsons and their infant son Jack, Jr. moved into a tiny, two-bedroom Brooklyn apartment where they shared a bathroom with the landlord. Eig’s narrative brings to life the strong bond between Jackie and Rachel Robinson and the support that she provided during her husband’s trying rookie season. A former UCLA nursing student, Rachel’s strength, intelligence, and compassion were obvious benefits to Jackie as they spent much of their time simply talking to one another in their small, windowless bedroom.

Outside the Robinson’s apartment, Brooklyn itself was changing. Robinson’s rookie season saw large crowd’s gather at Ebbets Field, the stands filled with both black and white fans. But as African American families were moving into Brooklyn, white families were heading toward the suburbs, namely on Long Island. The crowds at Ebbets Field didn’t last, and the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles ten years later, a city abundant with suburbs and automobiles. Eig writes, "Jackie Robinson packed Ebbets Field like never before, but his arrival signaled a cultural shift that foretold the destruction of Brooklyn’s lyrical little ballpark."

Outside the Robinson’s apartment, Brooklyn itself was changing. Robinson’s rookie season saw large crowd’s gather at Ebbets Field, the stands filled with both black and white fans. But as African American families were moving into Brooklyn, white families were heading toward the suburbs, namely on Long Island. The crowds at Ebbets Field didn’t last, and the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles ten years later, a city abundant with suburbs and automobiles. Eig writes, "Jackie Robinson packed Ebbets Field like never before, but his arrival signaled a cultural shift that foretold the destruction of Brooklyn’s lyrical little ballpark."

Beyond the personal and social perspectives, Opening Day provides a comprehensive recounting of what Robinson endured as a ballplayer. Vulgar cries from opposing dugouts. Threatened boycotts by white players. Not knowing where he stood with some of his own teammates.

And then there was the day-to-day roller coaster ride that makes up a baseball season. Slumps. Streaks. Injury. Worry of a demotion.

But above all, Robinson felt the constant and enormous pressure to succeed. Eig quotes Robinson on the great effort that he faced:

"There were times," he wrote, "…when deep depression and speculation as to whether it was all worthwhile would seize me."

Robinson, of course, did succeed and was named rookie of the year in 1947. For his career, he was a six-time All Star, National League MVP in 1949, and a National Baseball Hall of Fame inductee in 1962.

It’s hard to imagine Jackie Robinson not being identified with the game of baseball. But in Jonathan Eig’s wonderful recounting of that first season, it’s clear that Robinson overcame a degree of pressure that no other player had ever experienced. Baseball wasn’t his first love, not even when it came to sports. He had excelled at track and field, football, and basketball at UCLA. But he was a strong and determined man with a strong and determined partner in Rachel Robinson, and baseball was merely an avenue that these two people traveled in order to touch many other lives.