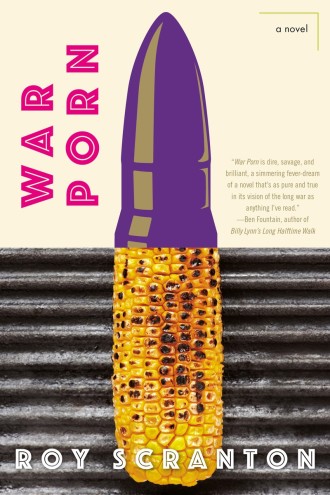

War Porn: An Interview With Roy Scranton

26.09.16

“The truth of war is always multiple.”

“The truth of war is always multiple.”

A few years ago I was struck upon hearing Roy Scranton begin a talk with this line. A simple statement, but its simplicity demands unending complexity— a complexity that exposes our blindness, we the American public, in the years of the Iraq War.

War Porn, Scranton’s debut novel, answers this demand for complexity with the force of a reckoning. One could describe the novel as three novellas that brush up against then seize one another. Perspectives upon the Iraq War multiply mercilessly: in “Strange Hells,” a recent veteran appears at a 2004 Columbus Day barbecue among twentysomething leftists; conflict escalates. “Your Leader Will Control Your Fire” offers the immediacy of a notebook written by a U.S. soldier in 2003 Baghdad. “The Fall” tells the story of the invasion and occupation from the perspective of an Iraqi family, centering on Qasim, a young math professor. Threaded throughout, brief gorgeous passages titled “Babylon” blend the discourses of this war vertiginously, moving us with a violent grace between these settings.

I first read a version of War Porn in manuscript years ago and have not stopped thinking about it. I spoke with Roy about the novel upon its release from Soho Books.

HILARY PLUM: Let’s begin where the novel begins: you chose to set your readers down first in the American home front, the Western landscape of Utah, amid a casual barbecue. We begin, then, as spectators, with the fact of the Iraq War entering in the figure of Aaron, the veteran; a dialogue about the war proceeds heatedly among intelligent, well-meaning characters with whom we may or may not wish to identify. The title War Porn also emphasizes, in force, the role of the spectator. Can you talk about why you began with this scene, this particular truth?

ROY SCRANTON: I wanted to bring readers in through Dahlia’s perspective because she’s one of the more relatable characters in the book. Here she is, among these young Americans in Utah, and the war doesn’t really seem to have anything to do with their lives: it’s noise on a distant channel. So what happens when the war comes home?

Dahlia is basically a decent young woman who’s trying to figure her shit out, and who longs for something more than the tedium she’s found herself stuck in. For her, there’s an unarticulated appeal in something dangerous, because it offers the possibility of breakage: breaking out, breaking open. But she doesn’t understand how dangerous Aaron really is.

The book’s three main sections are built like Russian nesting dolls, so the first and last sections are Utah, the second and fourth are Iraq during the war, and the third section, the middle section, is Qasim the Iraqi mathematician. I wanted to start where we’re at, the so-called “home front,” because I wanted to come back there after going through Wilson’s entire deployment and Qasim’s view of the American invasion. I wanted readers to experience the sense of seeing Baghdad as home, with Qasim, and the war as home, for Wilson, so that when we come back to Utah and the US we get something of that epic feel of returning to where you began from a whole new perspective. I don’t know if I succeeded, but that was the idea.

As for the central question of “war porn,” of war as spectacle and of war as narrative, it was very important to me in writing this book to not just offer another soldier story, “I went to war and war is hell.” I wanted to show that story in a context, in a frame that breaks its implicit claim to authenticity. That’s not new, of course, but even The Things They Carried has been so absorbed into readers’ understanding of war as a kind of ultimate authenticity that it’s hard to hear the real critique of narrative in that book. What we typically take from The Things They Carried is not that soldiers lie or make up stories, but that war is SO TRAUMATIC that language can’t capture it. “The real war will never get in the books” and all that. Well, that’s basically true of human experience in general, day to day life, going to the grocery store. Existence exceeds our ability to put it into language. Nevertheless, we tell stories.

But why do we tell war stories? What do we want from them? Why would anyone want to read a book like War Porn? I know why I read war literature, and it’s something inside me that connects me to Matt as much as it connects me to Aaron and Dahlia. I went to Iraq in part because I wanted to see. I wanted to know. In The Republic, Socrates tells the story of Leontius, who comes across some dead bodies lying on the ground outside the walls of Athens, where they were executed. He wants to look at them but he’s also repulsed and disgusted. He covers his eyes and turns away, but in the end he can’t help himself: he runs up to the bodies screaming, “Look, then, look! Take your fill, you wretches!” I wanted to put readers in that position and then make them conscious of it. I wanted us to look at how we look at war.

HP: And this is precisely what the novel achieves. I’ve been considering your phrase implicit claim to authenticity alongside the word representation. This novel commits bold acts of representation. At the center of its nested structure the fact of US torture in the “war on terror” is grievously present, a dark stain spreading through these narratives. The fact of torture—widespread, officially sanctioned—is one that many prefer not to see, not to foreground in their story of this war.

Another question of representation: the Wilson passages (“Your Leader Will Control Your Fire”) seem keenly self-aware in how they offer the strengths and satisfactions of “war literature.” The writing is bitingly vivid, moves so fluently through the speeds of boredom, violence, uncertainty, machismo—yet, too, there is a glimmer of metafictional awareness. The structure of the novel quietly comments on these passages, draws our attention to how the implicit works in your phrase implicit claim. Then in Qasim’s section, your style shifts, becomes lusher and more capacious in perspective; in the rhythms of the syntax and narration there is to my ear a gentle echo of great works of contemporary Arabic fiction as they arrive in English translation. One may discuss this as a question of “authority” and representation: to write from a perspective distant in language, ethnicity, culture from one’s own, a perspective indeed from the other side of a war. This too is an act that most American writers avoid.

Lastly, this question of representation intersects with that of biography. You are, of course, a veteran of the Iraq War. With Matt Gallagher you edited the anthology Fire and Forget: Short Stories from the Long War, a diverse representation of veterans’ writing; you’ve also written powerfully on how the veteran is represented in art and literature and how veterans represent their own experience, including in a recent essay in the Los Angeles Review of Books critiquing the conception of veteran as “trauma hero.” Now your biography is part of the story through which this book reaches readers, placing you to some degree in the role of “representing” veterans. I wonder if you could talk about some of these acts of representation—inside the novel and outside it, if the two can quite be separated—and how you’ve approached them.

Image: Hannah Dunphy

RS: Glossing Claude-Levi Strauss’s insights into structural anthropology, Fredric Jameson writes in The Political Unconscious that “the individual narrative, or the individual formal structure, is to be grasped as the imaginary resolution of a real contradiction.” This basic interpretive lesson, that our stories and myths offer us imaginary solutions to real contradictions, poses an interesting problem to the writer. What is one’s relation to the contradiction? How do we represent the contradiction? I think one of the best ways to approach this problem is through form.

There are several real contradictions at work in American culture and literature today that manifest in War Porn. One is between the mythic, artificial, imaginative, and empathetic promise of fiction, that it can take us somewhere else, into someone else’s soul, open up the world for us, and the contrary demand that our fictions be authentic, real, based in personal and factual truth. This isn’t a new contradiction—Melville has a great riff about it in The Confidence Man—but it is a live one, especially when it comes to war literature, doubly so when it comes to war literature by veterans, who are supposed to carry the authentic truth of war in their very psyches. The polyphonic structure of War Porn is intended less to solve this contradiction than to embody it, to create a formal structure that can hold and give shape to the many contradictions at work in the question of telling the story of America at war.

So the Wilson sections, many of which are drawn from my own time in Iraq, are in this “authentic” war-writing style, vivid, laconic, metonymic, with occasional flights into lyricism, which is the dominant style of writing in American war literature going back through O’Brien and Herr to Hemingway, even Crane. These sections are, as you suggest, not only narratively but formally in contrast to the Qasim section, which is in a style more in the tradition of the postcolonial novel, world novel, or novel in translation. My model here is not strictly the Arabic novel in translation, though that’s in the mix, but also Indian, West Indian, and African postcolonial fiction. I don’t mean to elide real differences between different traditions—obviously the Indian postcolonial novel is different from the Turkish postcolonial novel is different from the Nigerian postcolonial novel—but rather to think through the way the postcolonial novel as such functions within an American literary marketplace and cultural imaginary. The Dahlia sections are yet another style, “contemporary American literature,” with free indirect discourse, a slightly off-kilter, satirical tone, and “showing not telling”: a close focus on lifestyle and personality that fuzzes out context and social structure. The way these three kinds of narratives—war novel, world novel, literary novel—are usually isolated genres suggests something about the way we compartmentalize our imagination in response to the complexities and contradictions of living inside the American empire. My intention in juxtaposing these three narratives, insofar as it was conscious, was to give shape to these contradictions. I don’t know if I can “solve” them—I think War Porn is pretty pessimistic when it comes to solutions—but I’m also not sure that I want to or that it’s my job. They’re the contradictions we live with. I want to make them visible so we can talk them out instead of acting them out, as we so often do, through politics and political violence.

HP: Yes—I’m tempted now to ask you about the lived experience of this movement between forms. In 2015 you published a galvanizing book-length essay, Learning to Die in the Anthropocene: Reflections on the End of a Civilization, which employs personal essay and the tradition of the humanities, largely conceived, to offer a compelling meditation and polemic on the epoch of climate crisis. You’ve written journalism for Rolling Stone and elsewhere, including the devastating “Back to Baghdad,” on returning to Iraq amid the 2014 elections. You write across myriad forms and exhibit a formidable sense of how each form contributes to specific cultural conversations—as above, where you note the differences among the subgenres of war novel/world novel/literary novel: each is published and received differently, each arises out of and re-inscribes a tradition, a readership.

I’m curious to know more about this work in personal terms: what draws you to the novel in your own life. That the novel still seems live to you as a discursive form, still has this potential to offer even “imaginary resolution,” comforts and inspires me. The novel is a hard form to defend yet a hard form to abandon. It is both fairly marginal to the larger culture and yet persistently entangled in problems of market and capital—apprenticed often embarrassingly, for instance, to Hollywood. Often one finds that one has read a truly great contemporary novel and only, like, three other people have read it. And often formally challenging, provocative works of fiction, such as your own, don’t have a clear path toward publication. For you, then, why the novel? Can you talk about the years of living in this form, why it demanded that you inhabit it?

Image Source: Los Angeles Review of Books

RS: Why write fiction at all? This is something I wrestle with. I think that has to do with my searching out ways to survive childhood, finding in novels an escape and a freedom from the raw emotions of family life, the incessant barking of the television, and the painful limits of growing up poor in America. Novels offered not only respite but a wild freedom, not only release but revenge: I was especially fond of horror, fantasy, sci-fi, particularly post-apocalyptic narratives—Riddley Walker, A Canticle for Leibowitz, The Stand, Lucifer’s Hammer. It was a way of surviving, a way of holding the world at a distance and, as with any art, translating it into terms over which I felt I had some control.

I don’t remember intending to become a novelist, though, until my freshman year of college. That year was a total shitshow for a bunch of reasons and I wound up spiraling into a deep depression then dropping out. I was the first person in my family to go to a four-year university, so my sense of failure was catastrophic: not only was I failing myself and my own ambitions, but I was disappointing my family and their hopes, especially my mother’s. She’d become pregnant with me while she was still in high school, which spoiled her hopes of going to college. She did get her GED and, decades later, earned a bachelor’s degree, for which I’m immensely proud of her, but I think in many ways and for a long time I was the vehicle of her intellectual and artistic aspirations, and after I dropped out of college I felt I’d failed her about as badly as possible.

That summer I got a job driving a truck, and from that nadir, I couldn’t find any real way forward except to write: I could either reinvent myself in language or let myself die. There really wasn’t any other option. My entire life since then has been a consequence of that desperate lunge.

As to the bigger philosophical, critical, or aesthetic question of “Why the novel?,” I think the answer lies in the novel’s ability to embody consciousness, especially multiple consciousnesses, we might even say the multiplicity of consciousness, in the sense of the Greek logos, Hegelian spirit, noösphere, or hivemind. The truth of war is always multiple because truth is always multiple, because we are always multiple, because I am always multiple—je est un autre. Language itself is already multiple, because it’s both spirit and matter: language is consciousness translated into sonic vibrations and physical marks, aural and visual stimuli. Written language is the crystallization of consciousness from physical process into physical form—thought made flesh.

The novel, then, insofar as it remains an ill-defined, experimental, polyphonic, bastard form, seems to be the most capacious and sophisticated machinery we have for turning existence into language. A novel contains multitudes, it gives shape to thought, it exists—like a symphony—both as a whole and complete object, and as a continuous process experienced only in time. It can directly absorb and repurpose any kind of written genre, from philosophy to song to advertising, and it can engage with and enter into dialogue with music, film, visual arts, and any human activity, from a Catholic mass to a mass hallucination. It can not only show but actually embody the way in which language is never our own, never under our control, but rather a kind of spirit that moves through us, that speaks us. Each of us lives within and gives life to the collective history of our language, even as we misperceive, disagree, and wound each other in our alienation from it. The novel is a way of turning those relationships into an object we can reflect upon.

That’s a dubious and no doubt unsatisfying answer. As to the social utility of writing novels—who can say? Our savage children will pluck their flowers from our graves, the slag-heap of global capitalist civilization, and go on their way willy-nilly. Narrative makes things easier to remember, so there’s that. We work in the contradiction, and perhaps the polyphonic, marginal, bastard novel can help us see the contradictions we live in. As long as there will be humans, there will be humans telling each other stories.

HP: Dubious and unsatisfying are right, though, because it’s just such restlessness that drives the long form of the novel, the daily return to the desk. I want to ask you a traditional final question, but also to cheat and let it be two questions. First, on the Iraq War: your novel is coming out in summer 2016, thirteen years after the war began. The machinery of the novel requires time. Other literary works of note that address this war have lately been arriving—Philip Metres’s Sand Opera, Eric Fair’s memoir Consequence; works in translation have in recent years begun to find readers here, by Hassan Blasim, Sinan Antoon, and others. The truths of this war keep multiplying, not only through the gradual processes of culture, but as the aftermath of the war—drone warfare; the rise of ISIS; the effects of environmental devastation and depleted uranium in Iraq; the fearmongering taking place right now at the RNC in Cleveland; these only a few examples—proliferates. I’m interested to know how you might predict the course of the representation of and reckoning with the Iraq War: what work seems to be happening now, what work has yet to be done?

Second, to return again to the personal: I’d love to know what you yourself are working on, what’s next for you.

RS: I think the best American work about the Iraq War specifically and the war on terror in general has been done by civilians. I think a lot of so-called “veteran writers” are too invested in redemption, in recuperating some sense of themselves and their experience at war as fundamentally good and decent, and that this desire for redemption has made them sentimental and weakened their integrity as writers. It’s a tendency I saw and fought against in editing Fire and Forget, but over time it has only seemed to grow stronger. I very much admire the work of people trying to think through our contemporary contradictions, the realities of human evil, collective political complicity in an illegal war of aggression, structural violence, racism, and torture, and global American militarism, and it seems that most of the people doing that work in fiction and poetry are civilians, not veterans. Such work by civilians is also often much more interesting formally, as craft. This is not to say that there’s not some good work being done by so-called “veteran writers,” which of course there is, nor that there haven’t been some execrable, sentimental, jingoistic novels by civilians, which of course there have been, but only to note a tendency.

We should count Iraqi and Iraqi-American writers among those civilians doing interesting and honest work, though they inhabit a third, unnamed category, neither “veterans” in the sense of having been soldiers nor “civilians” in the sense of being outside the war. I’m grateful for Salaam Pax’s The Baghdad Blog, for instance, Sinan Antoon’s novels and poetry, Dunya Mikhail’s poetry, Wafaa Bilal’s art-document Shoot an Iraqi, Inaam Kachachi’s The American Granddaughter, and Hassan Blasim’s scarily brilliant collection The Corpse Exhibition. I also look forward very much to Jonathan Wright’s forthcoming translation of Ahmed Saadawi’s Frankenstein in Baghdad, which won the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2014.

As for what’s yet to be done, A.B. Huber, a scholar at NYU, once suggested that the great novel of the war on terror would somehow fold together the story of Chelsea Manning and drone warfare. I thought this was a remarkable provocation. I would also like to see something along the lines of a fictional version of Nir Rosen’s book Aftermath. That book is, in my opinion, the very best on-the-ground journalistic account of Baghdad during the war, and much of its virtue lies in Rosen’s painstaking, street-level reporting among both Iraqis and Americans. I fantasize sometimes about a fine-grained, 900-page-long novel about one neighborhood in Baghdad, say al-Dora or the Mansour, in the style of The Wire, tracking both Iraqis and Americans over five or six years of the occupation. Writing that properly would require knowing Arabic and going back to Baghdad again, though, so it may be out of my reach.

I also have some other, non-Iraq-War projects lined up. I’m currently finishing a work of criticism and literary scholarship, The Politics of Trauma: World War II and American Literature, which is the fruit of a decade’s thinking critically about war, literature, and the role of the veteran in American culture. I have another novel in draft, a “road movie novel” about freedom, violence, and art. I have some other ideas for the near future, including a noir thriller and something philosophical on materialism. But it’s really all about the daily return to the desk, as you put it: sentence after sentence, paragraph after paragraph, recreating existence in language. I never intended to write a book about climate change, but when the confluence of desire, need, and opportunity emerged, I knew that I had to write Learning to Die in the Anthropocene. My next project may be just as much a surprise. That’s part of the joy of writing, the sense of exploration, the wild freedom: the void of the page can open anywhere.