Video Killed the Film Director

08.10.06

Like licorice or macramé, David Lynch’s movies are a rarified taste. You either get it in toto, or not at all. Lynch is a known Civil War buff, and if his movies have drawn their own Mason-Dixon line, then the chill between North and South was palpable at the two press screenings of Inland Empire I attended last week at the New York Film Festival. The Get-Its buckled during every funny moment, while everyone else—the Don’t-Get-Its—intermittently exhaled loudly enough for the Get-Its to hear them.

Like licorice or macramé, David Lynch’s movies are a rarified taste. You either get it in toto, or not at all. Lynch is a known Civil War buff, and if his movies have drawn their own Mason-Dixon line, then the chill between North and South was palpable at the two press screenings of Inland Empire I attended last week at the New York Film Festival. The Get-Its buckled during every funny moment, while everyone else—the Don’t-Get-Its—intermittently exhaled loudly enough for the Get-Its to hear them.

Just before the closing scene of the movie—which runs exactly one minute shy of three hours—the screen goes dark and stays that way for several seconds, reasonably giving the impression that the picture is over and the credits are about to roll. But then the screen lights up again for a totally unexpected coda. At the first screening I attended, when the movie started again for that one last gasp, the Don’t-Get-Its all groaned.

Tickets for the festival’s public screenings yesterday and this morning have been sold out for weeks, and because the buzz is true and IE is easily the most uncommercial movie Lynch has ever made, it still hasn’t found a U.S. distributor yet—which means it’s going to be awhile before you see it. That I am thus obligated to describe Inland Empire in only the vaguest terms is pretty convenient for me, since my initial reaction, as with all Lynch movies, is: what just happened?

Tickets for the festival’s public screenings yesterday and this morning have been sold out for weeks, and because the buzz is true and IE is easily the most uncommercial movie Lynch has ever made, it still hasn’t found a U.S. distributor yet—which means it’s going to be awhile before you see it. That I am thus obligated to describe Inland Empire in only the vaguest terms is pretty convenient for me, since my initial reaction, as with all Lynch movies, is: what just happened?

After an early screening of Lost Highway in February 1997, the first question Lynch had to field from an audience member was in fact, verbatim, “What just happened?” As if to fend off this line of inquiry, the booklet that accompanies the DVD of Mulholland Drive (Lynch’s 2001 de facto follow-up, since 1999’s The Straight Story was really just a work-for-hire diversion, though a good one) actually provides a purported director-approved list of "10 Clues to Unlocking This Thriller." Salon claims that its on-line guide to sussing out the chronology of MD is one of that site’s most clicked-on articles ever. The point is, if you’re the sort of person who expects stories to have clearly delineated causes and effects, to be logically ordered in time and space, to have discreet beginnings, middles and endings, or to have characters in the traditional sense—individual human beings who can be referred to by a single name and identity that doesn’t change midway through—then you will more or less feel snookered by all of Lynch’s films, at least from 1991’s Fire Walk with Me on.*

One woman at Friday’s press conference asked Lynch about the significance of the number 47 in Inland Empire. This struck me as more than a little obtuse, not just because there are way more important questions to ask, but because—and it’s not giving away anything to tell you this—I am personally much more curious about the numerological meaning of 9:45 pm.

___________________

*Again, The Straight Story is an exception, a project Lynch’s ex-wife and editor Mary Sweeney brought to him and asked him to direct. TSS is so conventionally understandable that, as my friend Richard pointed out, Lynch felt as though he owed it to his fans to warn them right up front in the title.

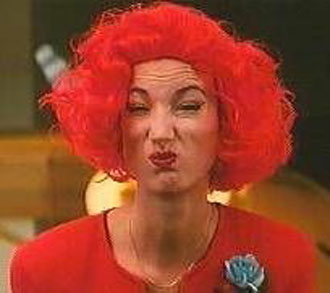

Unfortunately, Lynch got a lot of stupid questions on Friday. With each one, just before answering about as evasively as a congressional press secretary on the morning a pussy-hound scandal breaks (and yet with unusual politeness and calm––the benefit, presumably, of his 33 years of Transcendental Meditation), his face scrunched up. What he did was he made a sour face. It is easy to describe this sour face because it is the exact same sour face that Lil makes in Fire Walk with Me. Lil is the niece of FBI field director Gordon Cole (played by Lynch himself), and in the one scene in which she appears, she’s wearing a red dress and does this stomping-in-place jig while squeezing and unsqueezing her left hand, all the while tightening her features into the aforementioned sour face. Everything Lil is doing is in this G-Men code, and it’s intended to serve as a brief for agents Chester Desmond and Sam Stanley on what to expect as they begin their investigation of Teresa Banks’s murder in Deer Meadow. The sour face in particular signifies that there will be trouble ahead in dealing with the local sheriff. More important, though, is the blue-dyed rose pinned to Lil’s dress. Desmond, who has been translating the code for Stanley, says, "I can’t tell you about that.”

Unfortunately, Lynch got a lot of stupid questions on Friday. With each one, just before answering about as evasively as a congressional press secretary on the morning a pussy-hound scandal breaks (and yet with unusual politeness and calm––the benefit, presumably, of his 33 years of Transcendental Meditation), his face scrunched up. What he did was he made a sour face. It is easy to describe this sour face because it is the exact same sour face that Lil makes in Fire Walk with Me. Lil is the niece of FBI field director Gordon Cole (played by Lynch himself), and in the one scene in which she appears, she’s wearing a red dress and does this stomping-in-place jig while squeezing and unsqueezing her left hand, all the while tightening her features into the aforementioned sour face. Everything Lil is doing is in this G-Men code, and it’s intended to serve as a brief for agents Chester Desmond and Sam Stanley on what to expect as they begin their investigation of Teresa Banks’s murder in Deer Meadow. The sour face in particular signifies that there will be trouble ahead in dealing with the local sheriff. More important, though, is the blue-dyed rose pinned to Lil’s dress. Desmond, who has been translating the code for Stanley, says, "I can’t tell you about that.”

Most of the answers people seem to want after viewing a Lynch film have to do with plot elucidation, or the interpretation of a visual symbol, e.g. a blue rose. But the mundanely pervy-psychotic atmosphere of these movies and the mundanely pervy-psychotic feelings they uncomfortably provoke in us, have everything to do with how nonplussed we are over the most basic things—such as, what just happened. In other words, Lynch’s films are blue roses: they are compelling precisely to the degree we don’t understand them. The shards will never fit back together neatly, though they fit just enough to make you desire for them to fit.

It’s no surprise that the best essay ever written about Lynch is by David Foster Wallace.* DFW’s allergy to linear narrative, his intuitive overuse of digression and non sequitur, and his limitless ability to defamiliarize the matter-of-fact just by treating it so matter-of-factly matches ideally the specific category of weirdness we call Lynchian.

___________________

*Whose, yeah, circumlocutory style, I’m quite obviously emulating here. Listen, you try writing about David Lynch while maintaining a straight line.

Without ruining anything, I can happily report that most of the usual Lynch iconography—amputees*, empty theaters, ladies of the evening, the zig-zag floors and red drapes, blondes transforming into brunettes and vice versa, rockabilly hairdos, black coffee**—is all there in IE, though after two viewings I still haven’t spotted a dwarf. And this is what I want to emphasis: it’s not that there isn’t a dwarf in there, it’s just that I just haven’t spotted one.

Without ruining anything, I can happily report that most of the usual Lynch iconography—amputees*, empty theaters, ladies of the evening, the zig-zag floors and red drapes, blondes transforming into brunettes and vice versa, rockabilly hairdos, black coffee**—is all there in IE, though after two viewings I still haven’t spotted a dwarf. And this is what I want to emphasis: it’s not that there isn’t a dwarf in there, it’s just that I just haven’t spotted one.

___________________

*Amuptees are so, you know, Lynchian. What other director can count at least two different one-armed men in his oeuvre? There’s also the legless Amputee (1974), starring Catherine E. Coulson, a/k/a Margaret Lanterman, a/k/a the Log Lady, who carries her stump of wood around Twin Peaks with total exasperation, like it’s a hacked-off bodily extremity and she’s waiting for someone to show some courtesy and help her reattach it.

**Although Blue Velvet, by all accounts, is the source of Pabst Blue Ribbon’s current and annoying hipster ubiquity, it’s a serious understatement to say that coffee is the official beverage of Lynchiana. According to DFW, Lynch himself is a "prodigious" coffee drinker who quaffs so much of it on-set that it’s an apparently unremarkable event when the director, between takes, pees in plain sight of his crew against a nearby tree.

One of my favorite moments in all of Lynch takes place inside Twin Peaks‘s Double R diner where a couple of high school girls, Donna Hayward and Audrey Horne, are sitting along the counter on a Sunday afternoon after both have been to church. Audrey is lovesick over Special Agent Dale Cooper, who is in turn obviously nuts about her because she’s played by Sherilyn Fenn, but who in a later episode, because he’s an FBI agent and she’s jailbait, has to literally kick her out of his bed. Audrey has a cup of coffee in front of her but she isn’t drinking it, she’s running her finger around the rim of the cup and gazing distractedly into it in a way that a kid might who hasn’t actually acquired a taste for coffee yet and isn’t thinking about coffee at all but instead about the sort of things teenagers think about. Then Audrey asks Donna if she likes coffee. And because Donna hasn’t yet learned to like it either, replies "yeah—with cream and sugar." The virginal register is now firmly in place for Audrey’s breathy reply on the next beat: "Agent Cooper loves coffee. But Agent Cooper likes his coffee black." This exchange is about sexy as anything in Lynch, which is saying quite a bit.

In IE, Laura Dern and Grace Zabriskie share a pot of coffee in the living room of Dern’s manse. The camera moves in close as each cup is poured and both women drink it black, just like Agent Cooper.

Lynch shot Inland Empire on digital video using a Sony PD-150, which is a middling model that costs less than $3,000 and which has some solidly positive consumer reviews but gets nowhere near the resolution of a high-definition camera. The result is a lot of inky blotches up on the screen, where once again, in an entirely new sense, it’s not at all certain what just happened. As the preferred medium of surveillance and porn, there’s something both inherently lurid and threatening about video as a medium, and if you’ve seen Lost Highway, then you know Lynch is well aware of video’s sleazy-creepy rep and knows how to use it. One thing Inland Empire is resolutely about is video itself, its potential to rearrange the world as a ghostly feedback loop.* Then again, more than any previous Lynch film, IE resists interpretation—not just because it’s so aggressively non-linear but because, as I’ve explained, the images themselves are really fucking dark.

Lynch shot Inland Empire on digital video using a Sony PD-150, which is a middling model that costs less than $3,000 and which has some solidly positive consumer reviews but gets nowhere near the resolution of a high-definition camera. The result is a lot of inky blotches up on the screen, where once again, in an entirely new sense, it’s not at all certain what just happened. As the preferred medium of surveillance and porn, there’s something both inherently lurid and threatening about video as a medium, and if you’ve seen Lost Highway, then you know Lynch is well aware of video’s sleazy-creepy rep and knows how to use it. One thing Inland Empire is resolutely about is video itself, its potential to rearrange the world as a ghostly feedback loop.* Then again, more than any previous Lynch film, IE resists interpretation—not just because it’s so aggressively non-linear but because, as I’ve explained, the images themselves are really fucking dark.

___________________

*Michael Mann has received a lot of bullshit praise for his use of high-def DV in Collateral and Miami Vice. But whereas Lynch has worked to create an utterly new kind of spacial mystery using a medium that paradoxically collapses the depth of field, Mann instead kicks back and does what any teenager with a digital camera could do—make flattened abstract compositions that look really nifty. Suffice to say that Lynch—the practicing abstract expressionist—has the more painterly approach.

Rent one of the two DVDs Lynch has designed himself—Eraserhead or The Short Films of—and you’ll get the idea. Before delivering the viewer to the main menu, the DVDs require you to pass a crash course in TV recalibration, instructing you on how to adjust the “brightness” down until just a notch before the image disappears entirely.

Rent one of the two DVDs Lynch has designed himself—Eraserhead or The Short Films of—and you’ll get the idea. Before delivering the viewer to the main menu, the DVDs require you to pass a crash course in TV recalibration, instructing you on how to adjust the “brightness” down until just a notch before the image disappears entirely.

Lynch has made Inland Empire with a similarly fussy attention to light and dark. He’s less interested in the contrast between the two, than in using darkness as a ground and light as a figure. The very first image in IE is of a beam—it looks maybe like a searchlight or the headlight on a motorcycle—cast into pitch black. Lynch has never lacked for grandiose ideas, and the beam seems to imply the genesis of something in cinema. “For me, film is completely dead,” Lynch said Friday. “It’s a beautiful world we live in now.” He meant, of course, a digital video one.

Inland Empire is also the name of a group of counties between Los Angeles and the Mojave Desert. When Joan Didion wrote that, “California is somewhere else,” she was referring to places like the Inland Empire. In DV, Lynch has adopted a medium suited to guide him further into somewhere else’s labyrinth.

Photographs on pages 1, 5, and 6, and portrait of David Lynch, all courtesy Canal Plus.