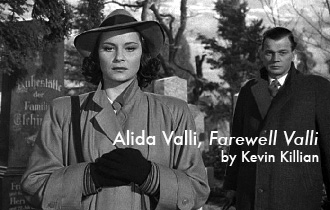

Alida Valli, Farewell Valli

29.09.06

Writing and re-writing this essay to mark Alida Valli’s death, I felt my ears perk up like a dog’s when the radio announcer cleared his throat, spoke out. “Veteran Hollywood leading man, Glenn Ford has died in his home in Los Angeles at the age of 90. Ford’s movie career began in 1939, and he became a star playing opposite Bette Davis in A Stolen Life and Rita Hayworth in Gilda.” Impatiently I sat there, half-numb, but half-keening like an old Irish peasant woman, my body bowing at the waist and bending back and forth slightly. Basically I was scornful—towards the announcer, poor guy. Basically it was a case of Tell Me Something I Don’t Know About Glenn Ford’s Multi-Storied Career! Well, the news of this untimely death was something I didn’t know, but how could he say anything about my beloved Glenn that could surprise me? He droned on about how Ford had excelled in noir in Fritz Lang’s Big Heat and in comedy in Minnelli’s The Courtship of Eddie’s Father, and in Capra’s Pocketful of Miracles.

Writing and re-writing this essay to mark Alida Valli’s death, I felt my ears perk up like a dog’s when the radio announcer cleared his throat, spoke out. “Veteran Hollywood leading man, Glenn Ford has died in his home in Los Angeles at the age of 90. Ford’s movie career began in 1939, and he became a star playing opposite Bette Davis in A Stolen Life and Rita Hayworth in Gilda.” Impatiently I sat there, half-numb, but half-keening like an old Irish peasant woman, my body bowing at the waist and bending back and forth slightly. Basically I was scornful—towards the announcer, poor guy. Basically it was a case of Tell Me Something I Don’t Know About Glenn Ford’s Multi-Storied Career! Well, the news of this untimely death was something I didn’t know, but how could he say anything about my beloved Glenn that could surprise me? He droned on about how Ford had excelled in noir in Fritz Lang’s Big Heat and in comedy in Minnelli’s The Courtship of Eddie’s Father, and in Capra’s Pocketful of Miracles.

Yes, yes, yes, I muttered, bowing with more fury, my body rocking in a rhythmic flutter. My hands gripped my abdomen as though cramps were racking me, but oh no, they were but grief and disbelief in a deathmatch clench. The same feeling you get when, as your postman gets run over by a bus, you say, “But he just delivered my mail yesterday! I just picked lint off the shoulder of his winter uniform yesterday! Just yesterday as he walked away from me I remember thinking, if only, my brother!” You can’t believe that life as you know it won’t go on and on and on, and that’s how I felt about Glenn Ford, for I had just spent the past week watching him romance Alida Valli and climb up Switzerland’s highest mountain with her in The White Tower (Ted Tetzlaff, 1950). Was any man more virile, young, or alive, ever more the embodiment of American virtue in a time when such a concept seems illusory at best, ubernasty most often? Who? You know how they used to lampoon Gerald Ford, and he even wound up self-deprecatingly admitting it, by saying, “You’ve got a Ford, not a Lincoln”? When it was Glenn Ford, we didn’t need Abe Lincoln.

I rewound The White Tower to the very beginning. Oh, that garish color! Doesn’t it sometimes seem that in the immediate postwar years every other Hollywood film was laid in Europe, if none of the good ones? Someone explained to me that this fancy of mine actually has a factual basis, and that Hollywood studios found that currency restrictions in various European countries prevented the proceeds of attendance at theaters from leaving the nation. So say that MGM amassed a fortune in France or Italy; they’d have no way of getting the money, much less spending it, unless they spent it over there. The White Tower opens with an establishing shot inside a bleak railway tunnel in the Swiss Alps, and then we, the engine, careen through the darkness into the light. A little railway station looms ahead in a pine-forest village and hanging over it, brooding majestically, the forbidden peak itself—the natives call it the “White Tower” because, well, it’s snowcapped and it’s huge. I would say ten miles high—is that possible? Cut to—close-up of a passenger, Carla Alton, anxiously sticking her head out the window to see if anyone’s meeting her train. She’s wearing a beret of a deep, velvety blue, and a complicated “New Look” suit with a blue-and-white houndstooth-type coat and a bright red scarf like the spirit of France. It’s Alida Valli all right—but wait, her beautiful dark hair, black as Diana Ross’s in Hitchcock’s The Paradine Case of a few years earlier, her black hair’s this sort of brownette shade, with a blonde streak right in the front of it. Maybe it’s to lighten her up, show she’s not the femme fatale in this one. But she sure is intense! She looks like Ingrid Bergman on a really awful day for Ingrid.

Instantly you can kind of tell what the whole movie is going to be about, especially when a donkey-drawn rattletrap fetches up to the station at “Kandermatt,” driven by two cute elderly bumpkins, Andreas and Nicholas, played by Oscar Homolka and Sir Cedric Hardwicke. It’s like she ordered two hams, and here they are. You get the impression from the grumpy, subdued looks on their faces as she kisses them merrily, that they’re not 100 percent happy she’s back in Kandermatt. I saw it right away. She’s there to climb the mountain and they’re worried about her safety. The wagon drives her back to Andreas’s chalet, which since her last visit to Europe he’s converted to a luxurious bed and breakfast, with a rathskeller in the basement, lots of good country cooking by Lotte Stein as Frau Andreas, and views out of every window of The White Tower.

Instantly you can kind of tell what the whole movie is going to be about, especially when a donkey-drawn rattletrap fetches up to the station at “Kandermatt,” driven by two cute elderly bumpkins, Andreas and Nicholas, played by Oscar Homolka and Sir Cedric Hardwicke. It’s like she ordered two hams, and here they are. You get the impression from the grumpy, subdued looks on their faces as she kisses them merrily, that they’re not 100 percent happy she’s back in Kandermatt. I saw it right away. She’s there to climb the mountain and they’re worried about her safety. The wagon drives her back to Andreas’s chalet, which since her last visit to Europe he’s converted to a luxurious bed and breakfast, with a rathskeller in the basement, lots of good country cooking by Lotte Stein as Frau Andreas, and views out of every window of The White Tower.

Eventually we piece out that years ago, Carla’s dad, the only man she ever loved, died on that mountain, in her arms. And as he lay breathing his last breaths, Carla vowed to make his dream come true—she would conquer the White Tower in his name—but then WWII came along and interrupted her dream, and this is her first time back in Switzerland since—well, since he died. We never do find out what Carla did during the war. I assume she was fighting the Nazis in one way or another because, well, she despises them! So does everyone else (in the movie). It’s like the whole Gunter Grass thing, there was de-Nazification going on everywhere in Europe, and yet for Hollywood, we will never forget. This becomes obvious when we meet another guest at the hostel, Major Hein—played by Lloyd Bridges of all people—your typical movie Nazi. Fellow guests attempt to freeze him out with icy contempt, and yet, what does he care, he’s been de-Nazified, free to spend his tourist dollar, I mean deutschmark, like everybody else.

Turns out he’s an expert climber too. The plot thickens! Lloyd Bridges must have made this film shortly before the blacklist set in, and he gives the part everything! He’s a healthy, red-blooded German male who makes no bones about his past in the SS, even wears Nazi uniform castoffs while sitting around the ski lodge. His attitude seems to be, I was a professional soldier. I lost, but next time I’ll win because I’m in perfect shape. Bridges’ flesh is solid, creamy, soft satin pulled taut over mounds of muscle. He makes Jeff Bridges look like a nothing. All right, I wouldn’t have picked him to be the Nazi in my movie, but perhaps his casting took the spotlight off some of the other actors in the film—especially Alida Valli herself. She’s practically spitting hatred at Bridges, and yet, what did she do during the war? She’s so “foreign”—where’s she from? Why does she go by just one name? The title card looks so weird: “Glenn Ford • Valli.” Is she too proud to go by two names like the rest of us?

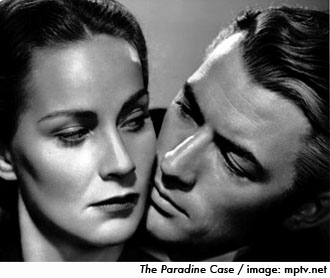

I guess I should back up because sometimes I forget there are people, filmgoers even, for whom Valli isn’t the ultimate movie icon. Some of us have never seen her in a movie, and some have never heard of her. At the time she was making The White Tower (in the title card in small letters underneath the great slashes of “Glenn Ford • Valli,” it says, “The services of Miss Valli by arrangement with David O. Selznick”), Valli was finishing out a Hollywood contract of some years’ standing. An Italian actress of some repute, she had made 31 films in Europe when Hollywood studio king Selznick spotted her during a talent hunt, and shipped her to California under exclusive contract. For four years he had loaned her out for a number of strange, off-the-beaten-path Hollywood movies— films always made more intriguing by her presence. In The Paradine Case, she channels the most forbidding aspects of Garbo, Bergman, Hedy Lamarr, Joan Bennett, and Satan. Hitchcock hated her, or so it seems; he doesn’t allow her character a single shred of decency. And yet he lets her be gorgeous in that unearthly way—she turns attorney Gregory Peck’s head and makes him ignore his pretty blonde wife Ann Todd—trying to prove her innocent of the murder charge lodged against her in a London courtroom; and she makes Louis Jourdan a sex slave who will do anything for the touch of her whip.

I guess I should back up because sometimes I forget there are people, filmgoers even, for whom Valli isn’t the ultimate movie icon. Some of us have never seen her in a movie, and some have never heard of her. At the time she was making The White Tower (in the title card in small letters underneath the great slashes of “Glenn Ford • Valli,” it says, “The services of Miss Valli by arrangement with David O. Selznick”), Valli was finishing out a Hollywood contract of some years’ standing. An Italian actress of some repute, she had made 31 films in Europe when Hollywood studio king Selznick spotted her during a talent hunt, and shipped her to California under exclusive contract. For four years he had loaned her out for a number of strange, off-the-beaten-path Hollywood movies— films always made more intriguing by her presence. In The Paradine Case, she channels the most forbidding aspects of Garbo, Bergman, Hedy Lamarr, Joan Bennett, and Satan. Hitchcock hated her, or so it seems; he doesn’t allow her character a single shred of decency. And yet he lets her be gorgeous in that unearthly way—she turns attorney Gregory Peck’s head and makes him ignore his pretty blonde wife Ann Todd—trying to prove her innocent of the murder charge lodged against her in a London courtroom; and she makes Louis Jourdan a sex slave who will do anything for the touch of her whip.

The Miracle of the Bells, Valli’s follow-up, is simply put one of the strangest film narratives of all time. A movie like Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind doesn’t hold a candle to it. Bells is a sordid blend of Americana, noir, social realism, Citizen Kane-lite, and God, anchored by four fine performances: Fred MacMurray as a slick-talking LA press agent marooned in a coalmining Pennsylvania village; Frank Sinatra as the socialist Catholic priest with a weakness for kinds; Lee J. Cobb as a Hollywood producer with a heart of glass; and Valli, a young actress from coal country who goes to Hollywood, gets her big break as St. Joan, and dies before the picture is to be released.

Next, Selznick loaned her out to Carol Reed for his now-classic Graham Greene thriller The Third Man. It was perfect for Valli, whose previous roles had all been circling under the titanic shadow of Orson Welles, and now she got to act with him in one of his greatest parts, Harry Lime, with Joseph Cotten as Holly Martins, charged with cleaning up the black market in contemporary Vienna. What did U.S. audiences make of Valli after this? I bet they were puzzled as me. In each film she had played a different nationality, so being Swiss in The White Tower was just another wave to her fans. What’s different about it is that she’s not mysterious. Paul Jarrico’s screenplay sets her up as the female hero of her own destiny. In that way it’s an unusual part for any actress in the year 1950. Very few movies in the 1950s held feminist leanings, and yet here Carla Alton displays a strong, self-possessed, athletic, moneyed, admirable subjectivity. She knows what she wants and she spends the movie getting it. Okay, so she’s a little driven…

“She acts wholesome, almost chipper,” Dodie [Bellamy] says, “but really she’s mysterious and foreign and stops there. She has a fleshy earthiness about her very unlike her contemporary, Dietrich, who was all skin and bones.”

“She acts wholesome, almost chipper,” Dodie [Bellamy] says, “but really she’s mysterious and foreign and stops there. She has a fleshy earthiness about her very unlike her contemporary, Dietrich, who was all skin and bones.”

Walk Softly, Stranger brings Valli back to the USA, to the same coal country that nurtured her in The Miracle of the Bells. In this one she plays Elaine Corelli, very much from the right side of the tracks. Her dad owns the biggest factory in town—Ashton, Ohio, in Cuyahoga County—and she’s been living the sexy playgirl life like Ingrid Bergman did in Notorious, until a freakish ski mishap in St. Moritz leaves her in a paraplegic state, and now she’s a shy stay-at-home recluse. Easy to do when you live in a gigantic mansion with your money and your memories. But no more dancing for Elaine, and no more mountain climbing either! In a way, Walk Softly, Stranger might be the sequel both to Notorious and The White Tower, not that Valli ever really seemed the super-active type like Katharine Hepburn. She was always languorous and she languishes just as exquisitely in her wheelchair—a chair that disguises itself as variously, a chaise longue, a park bench, and a little hassock at different parts of the picture. She is sad, sad, sad, but with a weary smile as though to say, I had my fun times, now let me spend the rest of my life a cripple. Now it gives me a chance to think of others. Last night we [Dodie and I] watched Bergman in the Rossellini passion play Europa 51, and it struck me how Rossellini must have seen Walk Softly, Stranger, for the predicaments he put Bergman through carry the same weight, and in the same places, of Valli’s suffering towards a glowing, Italianate spirituality.

Noir fans say that Walk Softly, Stranger, despite its noir-tastic title, isn’t really a noir,—it just tries to act like one I suppose because it was en vogue? Joseph Cotten plays a gambler and a con man, who just can’t go straight. He’s not evil like Uncle Charlie, but shiftless and lazy, and the one bright thing in his life is when he used to live in Ashton as a boy and delivered the newspaper to Elaine and her father. The big billboard that greets you when you come to town says, “ASHTON, a great place to live.” As Valli and Cotten prove, it’s a great place to redeem one’s self and to grow up a little. After their first date, Cotten asks her, “Did you have fun?” Her look says “No way.” He deflects her scorn: “Fun? It’s just a word. Throw it away.” If words aren’t getting you what you want, get rid of them. In postwar society we don’t actually need them any more (since we have guns, cars, and social mobility). By the end of the movie he’s headed to prison for a long stretch, and she says she’ll wait, he says he’ll need her, if it matters? “It matters to me,” she says. She’s almost simmering in Harry Wild’s sumptuous cinematography (Wild had just come off of making Joan Bennett sizzle in Renoir’s The Woman on the Beach, and he had given Dorothy McGuire the unbelievable Lana Turner makeover in Till the End of Time)—and Cotten sneers, “You’ll change.”

Not even the shadow of an expression crosses her face. “I’ll never change,” she states for the record. “I’ll always be the same, and I’ll always say it, as long as I live.” Prison bars stripe his face as the guards clang him in. Valli sits there in her miracle chair. She calls out, “Come back and see,” as though the whole film weren’t a progress towards mobility on the one hand, incarceration on the other. How about, “I’ll come back and see”? Wouldn’t that make more sense?

Not even the shadow of an expression crosses her face. “I’ll never change,” she states for the record. “I’ll always be the same, and I’ll always say it, as long as I live.” Prison bars stripe his face as the guards clang him in. Valli sits there in her miracle chair. She calls out, “Come back and see,” as though the whole film weren’t a progress towards mobility on the one hand, incarceration on the other. How about, “I’ll come back and see”? Wouldn’t that make more sense?

If you buy the recent Garbo boxed set they throw in as a bonus Kevin Brownlow’s recent TCM documentary on Garbo’s career. It’s okay. The glory part is seeing some clips from late in Garbo’s career, years after her farewell to film in Cukor’s Two-Faced Woman (1942). Apparently the independent producer Walter Wanger lured Garbo out of retirement by promising her the title role in a film of Balzac’s La Duchesse de Langlais. It had been filmed as a silent, with Norma Talmadge, back in 1922. Now Garbo could join the new U.K. screen idol James Mason in a Technicolor update—if Wanger could secure the financing, and he needed Garbo to make a screen test. But she’d been away from Hollywood for seven years—who knew if she still looked good? Wanger hired William Daniels, her favorite cameraman, as well as James Wong Howe, a photographer new to her, to make a pair of tests. Garbo complied. Alas, even though she looks spectacular, the money was not forthcoming. In seven years people had sort of forgotten about Garbo; new actresses had their attention—Ava Gardner, June Allyson, Jeanne Crain, Doris Day—and Alida Valli. What’s weird about Garbo’s screen tests is how much they’re directing her to be more like Alida Valli—a strange quantity—an unknown quantity that must have perplexed Garbo as much as it irked her. For who was Valli but an updated version of Garbo herself, with heaping spoonfuls of Ingrid Bergman sifted in? Look at the clips and see for yourself.

[You can view one of the Garbo screen tests online if you go to the website for the trailer company, Sabucat, and look for their so-called “samples.” This will be the one directed by “Jimmie” Wong Howe. Tell them Kevin sent you.]

After The White Tower, Valli’s contract with Selznick expired, and she returned to Italy. Immediately she was to inaugurate a whole new wave of revitalized Italian film, and made three of her best pictures back to back to back. She played the contessa in Luchino Visconti’s opulent period romance Senso (1954), then fisherman Yves Montand’s wife in the neo-realismo squalor of Pontecorvo’s The Wide Blue Road (1957); then she went all Existential in Antonioni’s Il Grido (The Outcry)—also 1957. She had a French period, laboring for Marguerite Duras in Rene Clement’s The Sea Wall (1958), and as the creepy surgeon’s accomplice girlfriend in Franju’s horror spectacular, Eyes without a Face, in 1960. She was still a star, of sorts, just no longer an American star. She was coasting, no longer top-billed, and she had a few uneasy years in the 1960s before yet a third generation of Italian auteurs put her back to work in a last burst of nutty glory—Pasolini in Oedipus Rex (1967), Bertolucci in The Spider’s Stratagem (1970) and several succeeding films, Mario Bava in the troubled Lisa and the Devil (1973), in which she’s blind and very grand. In 1977 Dario Argento handed her a great part, the mannish gym teacher, Miss Tanner, in his girls’ school masterpiece, Suspiria—playing opposite Joan Bennett almost as sisters who had never seen each other before. After that some of the oomph went out of Italian movies and people pretty much stopped watching them. She had brief parts in Argento’s Inferno, in Bertolucci’s La Luna. Kept working, died in April and ever since then, I’ve been strangely absent in the spring.