The Zoo

19.05.08

The Andean condor has been given a cow femur. Bits of meat cling to the blood-streaked bone. So far the condor is ignoring his treat. Flies are not. The condor’s dark body feathers and snow-white neck ruff make him look clerical. His head resembles a fistful of viscera turning to jerky. The femur lies on a patch of grass at the front of the cage, so centrally placed it seems the focus of the exhibit rather than that huge carrion snacker, who remains hunched in the background, puzzling over important spiritual questions.

For some of us, zoos serve the purposes of church. All we know of miracles is housed here. Zoos are also centers of refuge and exile. A rare homeless woman in a dirty muumuu wanders the zoo. She and I seem to be the only grownups here today wearing pink. This is not a good sign. How did she get in? Did she sneak? Admission is a steep $10 for adults. She talks to herself in a gentle undertone, as though reasoning with someone she likes. Every ten steps or so she curtseys and bows her head to some unseen (at least by most of the rest of us) creature(s) or deity(s).

An extravagantly patterned jaguar flips his tail tip back and forth and paces on huge padded feet. His eyes are luminous gold. His breathing is loud and shallow. A woman holds a baby up so it can see the frustrated cat. The baby is not looking at the cat at all, but twisting its head to stare, zombie like, at gawking members of its own species. The jaguar’s ragged panting stops. It draws in its tongue and freezes. Alert to the infant’s gurglings, the jaguar sniffs. You can almost make out a thought balloon suspended over the cat’s head with some feline equivalent to LUNCH! spelled out in claw-raked letters there. Despite barriers of metal pipe railing and hefty cage mesh, it’s nerve-wracking to watch mom brandish her bite sized baby, perhaps most so for the predator. When the infant’s back in its frilly pram, we bystanders breathe easier. The cat goes back to pacing and praying.

You are on the receiving end of a whole different vibe from tribes of zoo-visiting families and khaki uniformed staff if you are a middle aged adult tootling through the zoo alone, mumbling to yourself and taking notes, versus if you are the same disheveled, out of breath person hefting a cute 2 year old who’s stuffing goldfish crackers into his rosy little mouth. Visiting the zoo with a kid confers legitimacy. Too bad I can’t rent one at the gift shop.

The Aldabra Tortoise resembles a sun-baked boulder sculpted from alluvial mud. A distant cousin of his died last year in the Calcutta zoo at the age of 250. Seeing the pink tongue of this venerable specimen poke out when he is munching torn up head lettuce is a shock, like finding a blushing, juicy fruit thriving on a wizened tree.

The Aldabra Tortoise resembles a sun-baked boulder sculpted from alluvial mud. A distant cousin of his died last year in the Calcutta zoo at the age of 250. Seeing the pink tongue of this venerable specimen poke out when he is munching torn up head lettuce is a shock, like finding a blushing, juicy fruit thriving on a wizened tree.

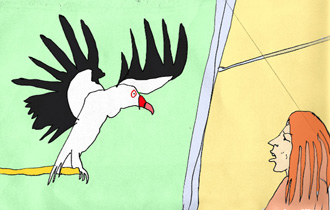

“Formal attire, dude!” a longhaired teenager exclaims, addressing the King Vulture. The guy has freckles, milky skin and straight, shoulder length hair the color of an Irish setter. He lets his mouth hang open as he watches the huge bird, so he looks either mildly surprised or always about to speak. The king he dares greet in this familiar manner sports black and white plumage and an arresting, sunset-colored head: peach, magenta, and yellow, and a startled, reptilian eye. He has a red and orange wattle. The shouted compliment excites the bird, who begins flapping landscape-shadowing wings, while maintaining a grip on his perch with grey talons. “Hanging ten on the branch like a guy who’s been surfing forever,” the young man says to his skinny companion. She’s a little taller than him, which she tries to minimize by slouching. She wears green converse sneakers (one untied) and a faded yellow print vintage dress. She has very blue eyes and dyed very black hair. The vulture ramps up his outlandish fanning, as if he could levitate the whole cage and fly it through the air, using his dead branch perch as a handle, if someone would only remove the roof. The other vulture, molting, half naked, remains huddled, looking unwell, though it’s hard for an avian layperson to tell just what a tropical lowland forest raptor might be feeling mid-molt.

When asked by his mother if he’d like to be any of the animals he’d seen at the zoo, a little boy in a bucket sunhat repeatedly declares he wants to be (not just a seal but) one particular dappled grey seal he points out as it spirals back and forth underwater with two spotty colleagues. He’s insistently specific, as if there’s a danger he might actually get his wish, but have his consciousness transferred into the wrong sleek, torpedo-ing seal. May our souls be projected only into the particular objects of our choice. And may our wandering spirits come back to us immediately and most gladly when we call them.

At the temporary elephant house, truncated by a large construction site from which bone rattling sounds of jackhammers rat-tat- tat, the lone pachyderm wanders back and forth across his dusty digs. Slowly, he eats carrots some unseen keeper lobs, one by one, into his pen. He crunches through a dozen of them. He doesn’t pick the carrots up with the “fingertips” at the very end of his trunk as expected, but conveys each to his mouth by bending his trunk almost in the middle and folding the carrot into it, then bringing the looped carrot to his mouth, like a person picking something up in the crook of their arm.

Although he loves and is deeply in tune with animals, my oldest friend refuses to visit the zoo, because of what he calls “the cage problem.”

“Tiffany” as her mother keeps frowningly addressing her, wants a quarter to operate the battered, shield shaped viewing-scope on this side of the giraffe enclosure. Her mother repeatedly asks if she knows what NO means. Tiffany has begun to ignore her. Still, the telescope stand with its three perforated metal steps allows Tiffany (and the rest of us, we take turns) an elevated vantage point from which to gaze up at the tallest living animal. When it’s her turn, Tiffany drapes herself over the viewer as though half melted and watches a male giraffe use his rubbery lips to pull and munch hay. One delight of witnessing this operation is the repeated slithering of the giraffe’s snaky black-purple tongue, which could belt at least once around little Tiffany’s waist, if she was willing to gird her loins with eucalyptus so the giraffe might find her enticing.

“Tiffany” as her mother keeps frowningly addressing her, wants a quarter to operate the battered, shield shaped viewing-scope on this side of the giraffe enclosure. Her mother repeatedly asks if she knows what NO means. Tiffany has begun to ignore her. Still, the telescope stand with its three perforated metal steps allows Tiffany (and the rest of us, we take turns) an elevated vantage point from which to gaze up at the tallest living animal. When it’s her turn, Tiffany drapes herself over the viewer as though half melted and watches a male giraffe use his rubbery lips to pull and munch hay. One delight of witnessing this operation is the repeated slithering of the giraffe’s snaky black-purple tongue, which could belt at least once around little Tiffany’s waist, if she was willing to gird her loins with eucalyptus so the giraffe might find her enticing.

The tiger’s roar, at least in captivity, is an enormous heaving groan that does what all laments should do: it carries for miles and makes the ground vibrate.

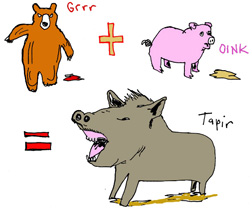

A hose-wielding keeper only partly visible behind a gated barrier squirts two mountain tapirs. A bear and a pig seem to have mated to produce this charming animal. The tapirs clearly enjoy the shower: they trot and leap, sprint and frisk, race straight into rooster tails of water. Sometimes they stop and point like retrievers. The same shaggy young man who was impressed by the King Vulture’s avid flapping remarks, “Look at this freestylin’ bro!” in reaction to the larger of the two tapirs’ antics. The tapirs are surprisingly graceful and dancey animals, given their dumpy appearance. But if the zoo teaches us anything it’s that looks can deceive. From signage I learn tapirs are “surprisingly agile and sure of foot,” and I feel ashamed for ever having thought otherwise. They are good swimmers, the text tells us, endangered, and their young “look like reddish-brown watermelons.” Baby tapirs are striped. A thin, bright white line marks these two adult tapirs’ lips as though drawn in chalk. Their ears are also edged in white. Tapirs are said to whistle. They possess a prehensile nose, about half the length of my forearm, a bit like a portion of elephant trunk, but not at all wrinkly. Their snouts are flexible and expressive. The tapirs’ wooly coats are now soaked, sending them into more hopping and bucking paroxysms of what appears to be tapir elation. That mobile snout is fascinating. No one is asking but I want badly to be a tapir. I want to get in there with them. I have to restrain myself from calling out to the keeper behind the wall, “What are they like when you really get to know them?” like a rabid fan cornering a movie star’s chauffeur, wanting to know, oh anything about the luminous actress, focus of such shy, fiery longing: what foods she especially craves, what kind of music she likes to fall asleep to late at night, what makes her laugh.

The rhino sleeps in the shallow moat separating the main plateau of his abode from us. So if you lean over his enclosure’s brown plastered rim, painted to look like mud, and reach straight down, this armored car of an animal is almost close enough to touch. Not that I would do such a thing, violate the rhino’s personal space. But one does very much want to feel the fist sized bumps patterning his flanks and rump: convex, uniform dents that look machine-punched into some hybrid of distressed leather and metal. “She’s pretty old,” a paunchy zoo docent tells the mother and sleepy tot next to me. How old, I want to know. “Thirty eight” he says, swiveling my way, beaming, so glad to have been asked. The mother exclaims, “The rhino and I are exactly the same age!” She looks at her kid as though to confirm the auspiciousness of this, but 38 is apparently too high a number to interest him. She’s seated her boy, who looks to be about 3, on the lip of the waist high front wall of the rhino’s pen so he can peer down and see the ton and a half animal napping practically at our feet. Mom’s got both arms wrapped tight around the kid’s middle. The boy rests against her torso like it’s the back of a chair. But his legs are angled awkwardly out of the enclosure, not dangling over the edge in the more natural position. A roving keeper in electric mini jeep scolded this pair earlier about leg dangling over enclosure rims while they attempted to view the reclusive bear. So now the little guy must do a serious yoga twist if he wants sit in the most logical spot for him to see animals from. The docent points out what bad shape the rhino’s horn is in. It does look hacked, like a small tree stump someone took a dull axe to. “We’ve been putting medication on it,” he remarks, tenderly. I ask if the rhino has a name. “Oh yes,” he says. “But I can’t tell you what it is. Only her keepers are allowed to use her name. It’s a very special thing. So they can communicate with her. So she’ll really respond to their commands.” The rhino’s private name never gets tarnished by visitors shouting it at her all day long. It will remain sacred. I would like my name to be kept quiet like that. I’d wish to have one common, everyday, sunfaded name, and another more pristine, powerful, heat seeking name I would reveal only to those who went to great lengths to gain my trust.

The rhino sleeps in the shallow moat separating the main plateau of his abode from us. So if you lean over his enclosure’s brown plastered rim, painted to look like mud, and reach straight down, this armored car of an animal is almost close enough to touch. Not that I would do such a thing, violate the rhino’s personal space. But one does very much want to feel the fist sized bumps patterning his flanks and rump: convex, uniform dents that look machine-punched into some hybrid of distressed leather and metal. “She’s pretty old,” a paunchy zoo docent tells the mother and sleepy tot next to me. How old, I want to know. “Thirty eight” he says, swiveling my way, beaming, so glad to have been asked. The mother exclaims, “The rhino and I are exactly the same age!” She looks at her kid as though to confirm the auspiciousness of this, but 38 is apparently too high a number to interest him. She’s seated her boy, who looks to be about 3, on the lip of the waist high front wall of the rhino’s pen so he can peer down and see the ton and a half animal napping practically at our feet. Mom’s got both arms wrapped tight around the kid’s middle. The boy rests against her torso like it’s the back of a chair. But his legs are angled awkwardly out of the enclosure, not dangling over the edge in the more natural position. A roving keeper in electric mini jeep scolded this pair earlier about leg dangling over enclosure rims while they attempted to view the reclusive bear. So now the little guy must do a serious yoga twist if he wants sit in the most logical spot for him to see animals from. The docent points out what bad shape the rhino’s horn is in. It does look hacked, like a small tree stump someone took a dull axe to. “We’ve been putting medication on it,” he remarks, tenderly. I ask if the rhino has a name. “Oh yes,” he says. “But I can’t tell you what it is. Only her keepers are allowed to use her name. It’s a very special thing. So they can communicate with her. So she’ll really respond to their commands.” The rhino’s private name never gets tarnished by visitors shouting it at her all day long. It will remain sacred. I would like my name to be kept quiet like that. I’d wish to have one common, everyday, sunfaded name, and another more pristine, powerful, heat seeking name I would reveal only to those who went to great lengths to gain my trust.

Geoffrey’s Spider Monkey swings through his cage using one hand and his looping tail. His free fist grips a floret of raw broccoli, which he is intermittently nibbling. To watch monkeys is to meditate on having hands.

The zoo is like a singles bar for toddlers. While there, they cruise each other heavily. Even tiny babies do. As soon as their eyes focus they begin to stare at one another with an obviousness that seems nearly brutal, and would never be socially acceptable for adults who weren’t already intimate or making a play to be lovers. A kid being pushed uphill towards the koalas may lean way out of his stroller trying to embrace another tyke being wheeled briskly downhill in the direction of the whooping gibbons. As these children make fierce, instant eye contact, it’s clear they’re ravenous to interact. And yet they are as ships passing in the night. The pram-navigating mothers (once in a great while it’s a dad) don’t see these thwarted affinities, these potentially life-changing missed connections, because most strollers have big sunshades, which canopy the kids from their chauffeurs’ view. Or the parents are simply wrong-headedly looking, as they so often are, at other stuff. For example, at Orangutans languidly chewing bamboo, or other parents scowling and picking whispered fights on cell phones. Unlike in a singles bar, these tykes who glimpse each other and hunger to meet don’t get to go home together, ever. Or at least not for years and years. Not till they learn to dress themselves, pass through the flaming Hades of puberty, hit drinking age, and meet again in a real bar. Then they’re transfixed by this eerie certainty they’re meant for each other, a feverish, hormone fueled belief they were entwined in a previous life. They never consciously recall the true genesis of their attraction: that once, long ago, they tried to grab each other’s sticky little chocolate ice cream blotched hands, before they even knew 30 words, right in front of a flock of Chilean flamingos.

The zoo is like a singles bar for toddlers. While there, they cruise each other heavily. Even tiny babies do. As soon as their eyes focus they begin to stare at one another with an obviousness that seems nearly brutal, and would never be socially acceptable for adults who weren’t already intimate or making a play to be lovers. A kid being pushed uphill towards the koalas may lean way out of his stroller trying to embrace another tyke being wheeled briskly downhill in the direction of the whooping gibbons. As these children make fierce, instant eye contact, it’s clear they’re ravenous to interact. And yet they are as ships passing in the night. The pram-navigating mothers (once in a great while it’s a dad) don’t see these thwarted affinities, these potentially life-changing missed connections, because most strollers have big sunshades, which canopy the kids from their chauffeurs’ view. Or the parents are simply wrong-headedly looking, as they so often are, at other stuff. For example, at Orangutans languidly chewing bamboo, or other parents scowling and picking whispered fights on cell phones. Unlike in a singles bar, these tykes who glimpse each other and hunger to meet don’t get to go home together, ever. Or at least not for years and years. Not till they learn to dress themselves, pass through the flaming Hades of puberty, hit drinking age, and meet again in a real bar. Then they’re transfixed by this eerie certainty they’re meant for each other, a feverish, hormone fueled belief they were entwined in a previous life. They never consciously recall the true genesis of their attraction: that once, long ago, they tried to grab each other’s sticky little chocolate ice cream blotched hands, before they even knew 30 words, right in front of a flock of Chilean flamingos.