Antonio Gaudi on Criterion DVD

23.05.08

Comparing notes with a critic friend once, she said that it was far easier to slam an album than a film, in that four-track solo recording projects can get dismissed out of hand (just ask my garbageman), while art departments with seven-figure budgets and a troop of set decorators cannot be dismissed so readily. Despite auteur theories to the contrary, film remains a collaborative art between a mass of people, disciplines (be they creative or financial), and departments. It’s a leviathan, a precarious relay from production to final product that can be derailed at any given link.

Comparing notes with a critic friend once, she said that it was far easier to slam an album than a film, in that four-track solo recording projects can get dismissed out of hand (just ask my garbageman), while art departments with seven-figure budgets and a troop of set decorators cannot be dismissed so readily. Despite auteur theories to the contrary, film remains a collaborative art between a mass of people, disciplines (be they creative or financial), and departments. It’s a leviathan, a precarious relay from production to final product that can be derailed at any given link.

The art form that bears the closest resemblance in sheer manpower is architecture, though a single auteur or Pharaoh often gets that credit too. We associate superstar architects like Rem Koolhaus and Santiago Calatrava with their vision and their buildings—there’s no room in the history books for underlings and collaborators. Yet in the recent Criterion DVD release of Antonio Gaudí, Japanese filmmaker Hiroshi Teshigahara’s reverent homage to the Catalan architect, Teshigahara hints (perhaps unwittingly) at this collaborative process by elevating the score of longtime collaborator Toru Takemitsu to a prominent position within the documentary. More than anyone else, it is this “voice” that resonates.

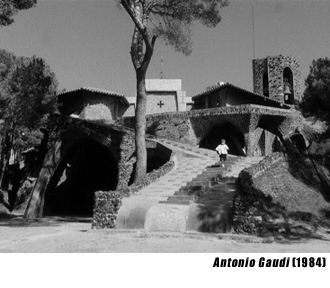

While not attempting here to fully unpack the place of Antoni Plàcid Guillem Gaudí i Cornet among the twentieth century’s pantheon of profound geniuses, certainly in a handful of increasingly controversial commissions he received at the turn of the century to design apartment buildings, public parks, and churches in Barcelona, Gaudi anticipated the twentieth century’s greatest art trends while making functional—albeit flummoxing—structures. Park Güell, Casa Vicens, Casa Batlló, La Padrera, Sagrada Familia:embedded in their tile and ironwork, their melting façades and flying buttresses turned arboreal, lay the seeds that would one day bloom into Cubism, Surrealism, abstract sculpture, the melting psychedelic art of the sixties, and avant-garde architecture: Gaudí is paternas familias to both Salvador Dalí and Pablo Picasso, Le Corbusier and Frank Gehry.

“The teacher is the tree outside the window,” the architect famously quipped, not only distancing his self from his creations but noting the True Creator (Gaudí increasingly became a religious aesthete and zealot). Such nature walk visions of Gaudi transferred to the realm of man, while the flux of nature transferred to his unbudging materials of metal and cement. As Teshigahara and camera roves through Barcelona, as viewers we too stroll and stumble upon these uncanny structures, which appear to be carved of stalactites, gigantic seed pods, rainforest plants, aquatic coral while also seeming otherworldly. Fibonacci spirals inform the stone staircases at Sagrada Familia, while the church’s nativity scene springs forth like Star Trek flora, an open palm with an eye in the middle of it. As the camera look on, so too does that eye appear to gaze back at us in the film.

“The teacher is the tree outside the window,” the architect famously quipped, not only distancing his self from his creations but noting the True Creator (Gaudí increasingly became a religious aesthete and zealot). Such nature walk visions of Gaudi transferred to the realm of man, while the flux of nature transferred to his unbudging materials of metal and cement. As Teshigahara and camera roves through Barcelona, as viewers we too stroll and stumble upon these uncanny structures, which appear to be carved of stalactites, gigantic seed pods, rainforest plants, aquatic coral while also seeming otherworldly. Fibonacci spirals inform the stone staircases at Sagrada Familia, while the church’s nativity scene springs forth like Star Trek flora, an open palm with an eye in the middle of it. As the camera look on, so too does that eye appear to gaze back at us in the film.

Yet the tile configurations, the wrought iron, the lampshades and railings spring not from Gaudí alone, but also from the handiwork of his craftsmen and collaborators, men relegated to footnotes, such as Berenguer de Palazol, Josep Maria Jujol Gibert, Domènech Sugrañes, Isidre Puig Boada, Bonet Garí, Juan Bergós Massó. It’s Jujol’s shards of tile on the snaking benches out at Park Güell that anticipate Cubism, the cantilevered lamps and vineyard lattices of metal from Pere Falqués that make the unreal tactile.

Teshigahara, while still a teen, made a pilgrimage to the city (captured on 16mm footage on the second disc of this set) to bear witness to these enduring structures, which made him realize “that the lines between the arts are insignificant. Gaudi made me feel that the world in which I was living still left a great many possibilities.” Teshigahara remains an intriguing figure in Japanese cinema. He was the son of Sofu Teshigahara, who founded a flower arrangement school and art discipline, Sogetsu. It’s one thing to rebel against a father who wants you to go into insurance, but quite another to buck against one who invented an entire art aesthetic. Still, Teshigahara avoided the family business and began to dabble in surrealistic painting, indebted to the likes of Spaniards such as Luis Buñuel, Dali, and of course, Gaudi, before moving into film. He worked outside of the studio system (a rarity in those days), setting up his own production company and making documentaries about woodblock artists and USA heavyweight champions. Amongst his circle of similarly inclined bohemian intellectuals, he commenced work on adapting the books of post-war existentialist scribe Kobo Abe for the screen, working closely with the author and composer Toru Takemitsu.

Three of these films, 1962’s Pitfall, 1964’s art house watermark Woman in the Dunes, and 1966’s The Face of Another were collected late last year in a boxset (also from Criterion), emphasizing the creative relationship between Teshigahara and Abe, yet curiously downplaying Takemitsu’s evocative input. The first collaboration is the confounding Pitfall. Part ghost story, part murder-mystery, part documentary exposé, part allegory, it’s a morass held together by Takemitsu’s outbursts of prepared piano, harpsichord, and echoing scrapes that resound as if from the bottom of a cistern. For 1966’s film The Face of Another, Takemitsu juxtaposes a stately Viennese waltz with eerie swells of glass harmonica. It can’t quite make the story of a man who has a face transplant work though. John Updike once called Abe’s no exit situations “cheap suspense” and a good source of “readerly exasperation,” and these two films are prime examples of it, feeling more like over-extended episodes from The Twilight Zone, pregnant with an inescapable dread. After another feature from this triumvirate, Teshigahara returned to his family’s business, a career interrupted only to bring Gaudí to fruition in 1984.

Three of these films, 1962’s Pitfall, 1964’s art house watermark Woman in the Dunes, and 1966’s The Face of Another were collected late last year in a boxset (also from Criterion), emphasizing the creative relationship between Teshigahara and Abe, yet curiously downplaying Takemitsu’s evocative input. The first collaboration is the confounding Pitfall. Part ghost story, part murder-mystery, part documentary exposé, part allegory, it’s a morass held together by Takemitsu’s outbursts of prepared piano, harpsichord, and echoing scrapes that resound as if from the bottom of a cistern. For 1966’s film The Face of Another, Takemitsu juxtaposes a stately Viennese waltz with eerie swells of glass harmonica. It can’t quite make the story of a man who has a face transplant work though. John Updike once called Abe’s no exit situations “cheap suspense” and a good source of “readerly exasperation,” and these two films are prime examples of it, feeling more like over-extended episodes from The Twilight Zone, pregnant with an inescapable dread. After another feature from this triumvirate, Teshigahara returned to his family’s business, a career interrupted only to bring Gaudí to fruition in 1984.

Despite the intervening decades between Teshigahara’s nascent explorations using a handheld 16mm to his cinematic career and return to Barcelona, the ordering of his film remains remarkably similar to those first impressions he captured in his home movies. He opens with shots of fountains, alleys, La Rambla, the city’s main thoroughfare. There is no telltale sign of Gaudi’s landmarks until nearly eight minutes in. Instead, he captures festive street scenes, the massive folk dances of the Catalan locals. It would seem comforting, quaint and folky, were it not for an overlay of ambient sound from longtime Teshigahara collaborator, Toru Takemitsu. In fact, were it not for Takemitsu’s contributions, there would be little to distinguish this film from those early home movies.

Credited as director, editor, and producer, what makes Teshigahara’s late work on the architect resonate on a visceral level is not so much the captured imagery but rather Takemitsu’s astounding soundtrack that moves alongside the visions. Eschewing documentarian earmarks like voiceover, talking heads, historical backstory, and polemics, instead it’s a half-hour before the first words are uttered, an hour before Teshigahara’s brief narration emerges.

Yet throughout, Takemitsu enthralls viewers with his cues and motifs, gives voice to the surreal imagery unfurling before us. Pipe organ themes somehow clothe the mysteries of faith in terrestrial notes, at times the timbres as melted, alien, and resplendent as the buildings themselves. A nineteen note descending scale recreates the vertigo that Sagrada’s spires inspire. Picturesque scenes of neighborhood life (these circle dances, live lobsters in the market, children dashing through Park Güell’s Doric columns) become foreign and disconcerting with an overlay of organic drones from a glass harmonica. Takemitsu’s music becomes syneasthetic, rendering and rearranging our sight anew, so that a truly alien world can be fully integrated into and inhabit this terrestrial one, yet remain transporting. While Teshigahara is no doubt the auteur, receiving the credit for capturing Gaudí’s architecture on celluloid, Toru Takemitsu encapsulates it best. In his structures are housed such celestial tones, the soundtrack here the most apt emulation of Gaudí’s own lifework.