The Pollock Streets: Ted Berrigan’s Art Writing, Part II

18.01.16

Editor’s Note: This is the second installment of Sturm’s piece about the art writing of Ted Berrigan. If you didn’t have a chance to read the first part, go here.

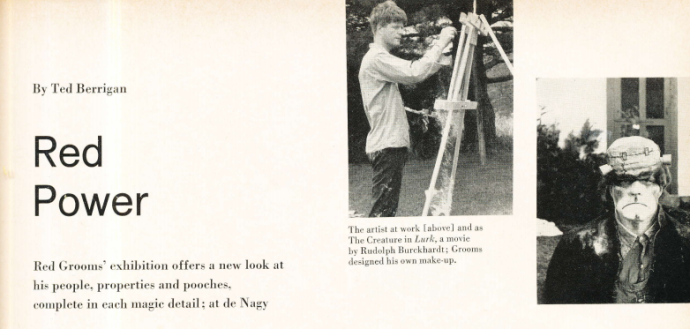

Berrigan’s last feature article for ARTnews, published in December 1966, is about painter and multimedia-artist Red Grooms, whose show at Tibor de Nagy he had enthusiastically reviewed in April of the previous year, describing Grooms as “one of the most imaginative and wacky artists working today.” The review, which is his longest gallery shot, shows Berrigan’s critical dexterity and range of artistic affinities: “His pictures and cut-outs are brimming with the energy of his commitment to the actual work of making art, and yet they are representational in a manner which simultaneously presents startling likenesses while evoking correspondences ranging from Expressionism to the Katzenjammer Kids.” The ability of an artist to fuse traditionally artistic forms with the pulpy comic entertainment of the everyday is what captures Berrigan’s imagination.

For him though, this amalgam of high and low isn’t simply an occasion for playfulness, but for what he calls a pervasive “spookiness” in Grooms’ work. Included in his review is a description of “a frightening portrait of Alex Katz which must have been done from about six inches from the model. This painting almost qualifies Katz for the Cosa Nostra, and its realness is the all-time answer to the old question ‘why paint what can be photographed?’” Realness as intimacy and proximity. I’m immediately reminded of the line from The Sonnets, “I like to beat people up,” a mistranslation of Henri Michaux, as it echoes in this image of Katz as a possible Italian mobster. This “scary quality,” as brightly hued as it is intimidating, seems to be the other side of the “awkward prettiness” Berrigan found in Freilicher’s paintings. “It’s as if in the natural rather than the supernatural,” writes Berrigan, “that the artist finds spookiness.” Again one thinks of lines from The Sonnets: “it flows directly and spontaneously / and O I am afraid!”

Painting by Red Grooms titled “The Levinson Family.”

In his 1966 article, Berrigan calls this ability of Grooms his “Red Power.” Continuing the earlier association with the comics, he writes,

I like Red’s paintings even better than the funnies, mostly because they are so much richer. There is more detail, less story, more mystery and less art as art. Because his paintings are not so neat, and because the people and things (tables, dogs, window-curtains, playing cards, hands) seem so important simply because they exist, Red’s paintings sometimes seem very scary. The domestic scenes he has painted, such as Loft on 26th Street, the cut-out painting of 1966, are much more haunting than they are delightful, despite their bright Pop colors and the near-comic air of domesticity they strike. In fact, there is something awful about the autonomy of each person and object pictured, as if someone or everything could very well go totally berserk at any instant and it would be just as logical as not.

The combination of a hectic, disorienting surface paired with a colloquial vision of representational depth was one of Berrigan’s own poetic modes. Grooms’s ability to charge a piece with intimacy, humor, and pathos, all the while approaching and appropriating the work’s own aesthetic influences with a witty, devotional self-reflexivity, seems to have made him one of Berrigan’s favorite artists at the time. That he describes his appreciation of Grooms’s paintings in narrative terms–“more detail, less story, more mystery and less art as art”–speaks to a turn in Berrigan’s writing signaled by the more immediately domestic, autobiographical poems that would appear in Many Happy Returns. This idiosyncratic approach to representing the personal runs through each of the three artists Berrigan wrote about in his feature articles, and it is worth noting how conscientious and passionate Berrigan is about portraits and paintings full of people. His poems have exactly that intricately layered devotion to the people in his own life, and like these artists, such representations were always about the poem rather than about the person, a valuing that never resulted in loss of feeling. The presence of people, of friends, was an occasion for making art.

About Grooms’s numerous images of people in his paintings, Berrigan adds an amusing, insightful addendum about comparing Grooms to the Japanese painter Hokusai.

Note: “Red Grooms is like Hokusai” I thought to say and poet Dick Gallup did say once, but then one of us said no, he’s not illustrating character; which is true. Red’s people have character, but even more than their own particular character(s), each seems to partake of the mysterious and somewhat frightening quality of otherness, each from each and all from all, including ourselves.

Berrigan’s clever syntax, never absolutely attributing the thoughts and speech to himself or Gallup, enacts precisely the uncanny omnipresence of what is “true” in Grooms’s paintings, the mysterious “Red Power.” One thinks of how some readers of Berrigan insist on reaching into the biography of the names that appear so often in his poems, “Ron,” “Marge,” “Chris,” but how in the accumulating rooms of Berrigan’s poems the names, though always “true” names, are more a kind of formal space for character and otherness to intermingle than a litany of proper nouns. Each “character” then becomes a word choice, a “magic detail,” as he says of Grooms’s paintings, that stutters and spreads out in the all-inclusive formal rush of the poem. Though likely not directly related, it’s fun to think of Berrigan’s later, well-known poem “Red Shift,” itself filled exactly with the “informal and shrewd, and a little show-offy” qualities he sees in Grooms, as having some nexus in this “Red Power.”

Berrigan’s article on Red Grooms from the December, 1966 issue of ARTNews

After his article on Grooms, Berrigan never returned to regularly writing professional art reviews. Other than a review of George Schneeman in Art in America in 1980, I haven’t found any other published examples of Berrigan’s art writing. As he explained in 1972, the work had become monotonous and the expectations of the artists and galleries had become too demanding, shortsighted, and career-focused. He put it bluntly, saying “I simply couldn’t stand it, I couldn’t write, I literally couldn’t do the reviews.”

At the same time that ARTnews “was a great place to work,” he saw the gallery scene as too much of “a serious world” for his taste. In a half-satirical, incredibly performative “Art Chronicle” piece for Lita Hornick’s magazine Kulchur in late 1965, written soon after starting at ARTnews, Berrigan totally slays Tom Hess and the soberer, more traditional practices of the magazine. A wily amalgam of appropriation, literary punning, and inside aesthetic jokes, the “Art Chronicle” essay includes a long passage from what Berrigan says is his recent Art International article on Henri Michaux. His citation begins: “On November 15th, 1934, when he published The Painter’s Elbow, Michaux also stated that ‘I paint in sin.’ In Paris Henri Michaux had issued explicit orders to stop the itching of how and why.” Of course, November 15, 1934 is the date of Berrigan’s birth, Michaux never published a book called The Painter’s Elbow, and Berrigan never wrote for Art International. If it seems like this thick litany of prankish inventions houses nothing more than Berrigan’s punning and joyfully lame transformation of the sexual idiom about an itch you can’t scratch, you might be right. What was valuable to Berrigan about the practice of art criticism was not, like The New Yorker’s Harold Rosenberg, whom Berrigan calls “a dunce” in another article, the ability to make insightful, judicious descriptions of an artist’s process and style, or to claim critical authority over an aesthetic, but simply to have fun writing about art as an artist and to be entertaining while doing it.

Reading through Berrigan’s Kulchur contributions are a case in point, such as his two pages of a faux-translated passage supposedly from Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space that, among other things, references how “the limp and misty sausages of Francis Bacon glut the imagination.” Like the literary send-ups in the collaboratively written Bean Spasms, Berrigan is reveling in his coy, transgressive assault on official art cultural. A sin, indeed. When he says later in an interview, “I loved working for Tom Hess actually,” he’s probably being honest. Writing for ARTnews was a good gig while it lasted, though the Kulchur article shows how Berrigan necessarily pushed against whatever boundaries he was presented with aesthetically and professionally.

Of course, satirizing serious criticism was a repeated pleasure for Berrigan and his friends, such as in a June 1965 issue of Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts where Berrigan published a review of Norman Mailer’s An American Dream that is actually a William Burroughs-style, two-column cut-up of lines from Burroughs’ novels and other sources. “GET THE MONEY!” Berrigan mockingly chants in his pieces for Fuck You and Kulchur, his parodic, critical rallying call against the business of art. The faux-slogan was a way of simultaneously parodying refined culture’s rebuke of lower class profligacy while celebrating promiscuous acts of artistic appropriation and theft (the phrase itself Berrigan appropriated from Damon Runyon).

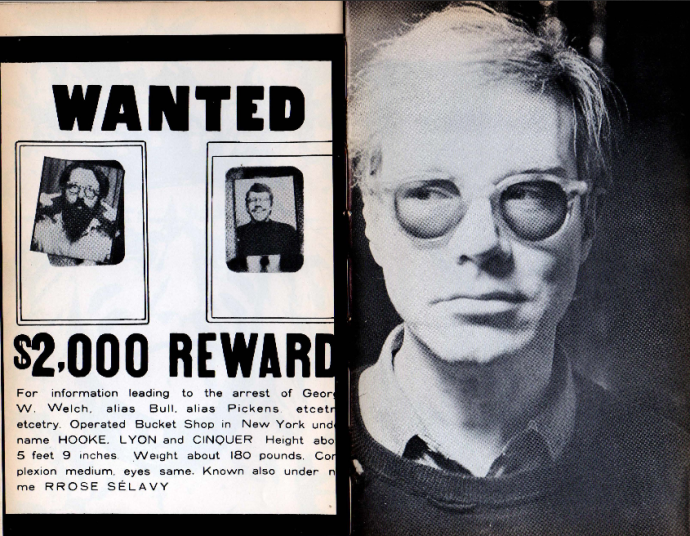

“I must confess that I plagiarized the last few lines of that review from John Ashbery’s catalogue piece,” Berrigan writes in a summary of a show of Joe Brainard’s in his “Art Chronicle” piece, “but wouldn’t you?” There was no room for that sort of blasé disobedience in ARTnews, and Berrigan was clear that he disliked how they would coldly edit his writing. Despite the differences in publishing philosophies, Berrigan managed to tow the line between the divergent attitudes at Kulchur and ARTnews, slyly exposing and performing within each magazine’s distinct aesthetic code, as well as their less visible socio-economic codes. The writing he did for Kulchur from 1964 through the magazine’s final issue in the winter of 1965 gave him a less restrained, rowdier space for writing book and art reviews. Berrigan’s inclusion of Brainard’s appropriated version of Duchamp’s famous “Wanted” poster after his “Art Chronicle” essay–with photos of himself and Brainard pasted over the photos of Duchamp, and a close-up portrait of Warhol coolly glancing over at them from the next page–attests to Berrigan’s playfully sharp intentions at Kulchur and in his art writing in general. That he could write for both magazines simultaneously is a testament to Berrigan’s keen social bearings as well as to his ability to pit his relentless allegiances, though never hard and fast, both with and against each other for the sake of a more audacious conversation.

“Wanted — $2,000 Reward by Joe Brainard, photograph by A. Malgmo” (A. Malgmo is not an actual person but some kind of pun-name that Ted, Ron, and Tom Veitch used to use) and on the right: “Photograph of Andy Warhol by Lorenz Gude” // citation info: Kulchur 19, Autumn 1965

It’s clear that Berrigan’s writing in ARTnews resonates with a serious, dedicated pleasure, and perhaps there are other reasons he turned away from the work. While it’s true that Berrigan was slyly self-deprecating about the quality of his journalism, beginning his Kulchur essay by announcing “[I’m] a good bet not to win the Lillian Ross award for 1965,” the sheer amount of writing he did for these magazine and journals attests to his shrewd adaptation of the form.

However, it seems he strayed from the work to pursue ways of getting the money. Once he started teaching at the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa in fall 1968, with later stints in Ann Arbor, Buffalo, Bolinas, Essex, and Chicago, Berrigan would be away from the thick, bustling gallery scene of the New York art world until the late 70s. It’s worth considering that O’Hara, who loomed large in Berrigan’s personal (anti-)canon, had tragically died in the summer of 1966, a loss that had a profound effect on him. O’Hara had worked for ARTnews in the mid-50s in the same capacity as Berrigan, reviewing openings and writing feature articles, and it’s possible to imagine O’Hara’s death affecting how the younger poet saw himself in the larger above-and-underground communities of mid-60s New York. Whether too put-off by art world professionalism or too haunted, Berrigan moved on. But looking back at that early writing now helps us to correct and complicate some of the hipster myths embedded in the more static, outdated narratives of Berrigan’s life and work. Most importantly, we can start to think about how else Berrigan’s lush, audacious, open work can be read and lived in connection with the visual artists he worked with, wrote through, and loved.