The Pollock Streets: Ted Berrigan’s Art Writing, Part I

07.12.15

For the last few months, I’ve been amassing folders and folders full of material on Ted Berrigan, tracking down stray pieces of prose and book reviews, making lists of unpublished poems, looking for parts of his prose work “Looking for Chris,” asking about an enigmatic collaborative novel from the early ‘60s called Malgmo’s End, and reading and rereading the criticism and scholarship on his work, from Perloff’s careless, irresponsible description of Berrigan’s “sexist fantasies” (I say this with great care, not only as a defense of Berrigan but as a indictment of Perloff’s systematic elisions) to Art Lange’s praise of his poems as “among the most enchanting and musical lyrics currently being written.” I’ve spent hours standing over scanners with mimeographed books and old periodicals. The supervisor at the library jokingly offered me an office in the basement. It’s been an archival summer.

One of the folders I have is labeled “Ted’s Prose.” Outside of his peers, the fact that Berrigan wrote much prose–an anthology introduction, serious, parodic essays, book reviews, a novel–is mostly unknown. But the “Ted’s Prose” folder is surprisingly thick, mostly with his writing about art in New York in the mid-1960s for the influential trade magazine ARTnews. What’s immediately clear from reading Berrigan’s art writing is that the New York art world was a scene that Berrigan was completely and happily entangled in. It was work that, threaded with friendships and his own aesthetic self-education, placed him in a direct lineage with the poet-art critics he most admired: John Ashbery, James Schuyler, and Frank O’Hara. And while these canonical New York school poets are celebrated for their ekphrastic aesthetics and successful careers as curators and art critics, the more teachable narratives of Berrigan’s life and the “second generation” New York school have not noted his role as an art critic. Reading the critical references to Berrigan, where he often appears as a minor character or footnote, it becomes hard to imagine him as someone who was meaningfully engaged in aesthetic practices with visual artists in a “serious” or even study-able way. Uncovering Berrigan’s art writing not only revises our narrative of his early life “taking in Art in New York,” as Alice Notley says, and shows a new link to the poets of the first generation, it also broadens how we can read the poems that surround his work as an art critic, particularly The Sonnets and his great, long poem, “Tambourine Life.”

In the early-mid 60’s, Berrigan was saturated in the aesthetic accelerant of the hybridizing New York art scene, regularly attending museums, plays, and operas, watching French New Wave films, avidly reading about the modernist avant-gardes, and collaborating with other poets and painters. He was a casual visitor at The Factory and Warhol even gifted him a Brillo Box that, as Ron Padgett describes, Berrigan “personalized” into a clustered, stained coffee table in much the same way he “personalized” lines from other poets into his own works, such as The Sonnets. It was a time of floating silver foil, cut-ups, and Blonde on Blonde and Berrigan stood giddily and seriously in the middle of it. In 1964, looking back at his first few years in New York, Berrigan writes “Joe [Brainard] and I used to go almost every day to art galleries and museums and drench ourselves in paintings, starting up at 86th street and Madison, and hitting just about every gallery from there to the [M]useum of Modern Art where we would sit in the garden and have coffee delirious with all that art and the way even the telephone poles and drugstores had turned into paintings after a few galleries.” These are “the Pollock streets” of The Sonnets, an aesthetic stage where Berrigan’s keen associational eye was able to trace a generative compendium of artistic influences and historical networks, such as when he claimed Jean Dubuffet “is Paul Klee as King Kong” after seeing a show of Dubuffet’s at MoMA. When Berrigan started writing for ARTnews in March 1965, it was part of his continued, fluid engagement with an intimate, generative community of artists.

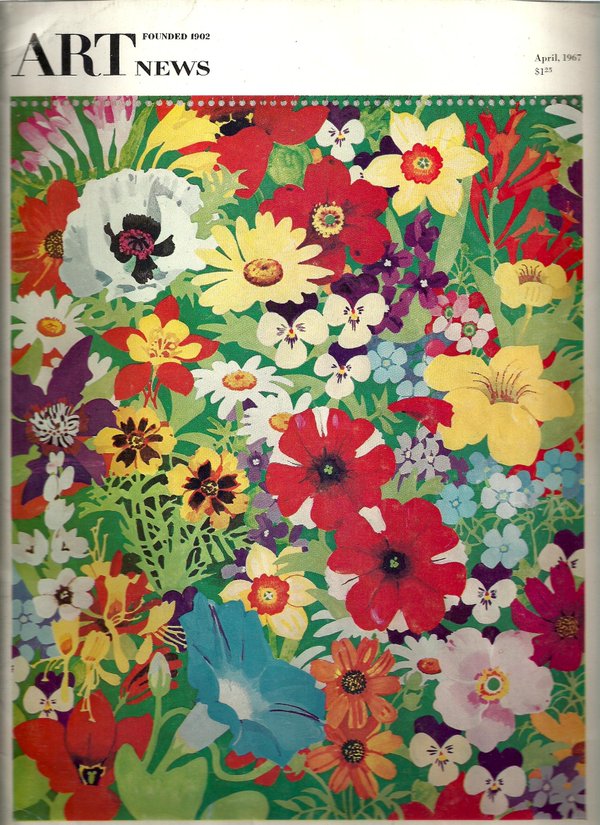

A year after the publication of The Sonnets with “C” Press, at the tail-end of publishing the incredible run of C magazine, and a few months before what he would jokingly call his “rookie of the year” appearance at the Berkeley Poetry Conference, Berrigan began a prolific period of writing for ARTnews. Coming on board as an editorial associate under the editorship of Tom Hess, Berrigan would contribute often and intensely. From March 1965 to December 1966, he wrote feature articles on Jane Freilicher, Alice Neel, and Red Grooms, as well as over 100 reviews of shows by artists such as Roy Lichtenstein, Sol Lewitt, and Hans Hoffman at galleries like Tibor de Nagy, Castelli, and Dwan. Tracking Berrigan through the artists he covered shows a young poet enmeshed in a prismatic, shifting art scene still bearing out the tension between a declining Abstract Expressionism and the burgeoning of Pop Art, the appearance of Minimalism and conceptual forms, as well as the influx of Op Art, Happenings, and a revival of Art Nouveau styles. Couched between Barnett Newman’s article on Abstract Expressionism and David Antin’s article on Warhol, and sitting comfortably alongside contributions from Ashbery and Schuyler, Berrigan’s ARTnews writing reverberates with an intimate, astute knowledge of contemporary art, its vocabulary, and its critical paradigms, all saturated with the pleasurably bent, candid perceptions that shimmer in all forms of Berrigan’s writing.

ARTnews, April 1967, cover by Joe Brainard

For the most part, Berrigan adopts the formal tone of the professional gallery reviewer, the “T.B.” initials following his reviews nearly absorbed into the wash of dozens of reviews that appear in every issue. For example, Berrigan’s review of an April 1966 show by Martin Hurtig at Alonzo Gallery seems to have left him especially uninterested; “paints in an Abstract-Expressionist manner” is the complete review. However, Berrigan’s wit, flair, and colloquial devotions often sneak in, such as in this review of painter Abby Shahn, also in April ’66:

Abby Shahn’s [Hinckley & Brohel] big wacky autobiographical paintings are as gay as Henry Miller, as sexy as Miro and as fresh as Smokey Stover. She is a sophisticated happy colorist; her cool daring makes for Harpo Marxist splashes of Gorky’s warm colors without sacrifice of control. In feeling the artist she most approaches is Red Grooms, but her charms are considerably more spontaneous. Like Grooms, Miss Shahn is a delightful and serious artist, a rare combination.

The cultural constellation built here, with its racy (and punning) allusions to interwar modernisms, soapboxing for screwball Sunday comics, and descriptions of color that maneuver between the burlesque of low, American-made entertainment and the drama of European-influenced Abstract Expressionism, is distinctly Berrigan-esque. Beyond these direct references, the aesthetic pairings suggested in his word choices could be useful descriptions for Berrigan’s own poems: work that is splashy and controlled, charming and spontaneous, delightful and serious. When he describes Carl André’s sculptures at Tibor de Nagy in mid-1965 in terms of “a child’s ‘Build a Log Cabin’ game,” noting that one piece looks like “a corral big enough for a horse,” we are seeing the austere, linear grids of the new Minimalism through the eyes of a poet who was just as pleased, and found just as much artistic value, in seeing matinees of Rio Grande as in mixing with New York City’s contemporary avant-garde. At times he swings from bawdy pop culture humor, likening the repeated shapes in a Barbro Ostlihn painting to the phallic cartoon character “shmoo,” to comparing a Joel Brody sculpture to “an Antonioni movie, but the seriousness seems a little higher,” all the while being willing to make whatever grand or mundane statement on behalf of what’s before him. “Pleasantly weird,” he says about Henry Pearson’s canvases. “While the paintings never fail to be impressive, they seem unable to escape out from their of yoke of being good,” he says, with his characteristic wit, about Mel Leipzig’s work. And about Robert de Niro, Berrigan sounds like a seasoned, high-end critic: “This show further establishes De Niro as an original and powerful American painter.”

Berrigan’s full-length ARTnews articles give a more multifaceted position to consider his devotions. Rather than strolling from gallery to gallery on assignment, Berrigan is enthusiastically invested in each of his three subjects and spends considerable time describing and clarifying the techniques of these artists, a serious activity that doesn’t discount his gracious, mischievous humor. In his November 1965 article on Jane Freilicher, “Painter to the New York Poets,” Berrigan gracefully illustrates the painter’s “passion for the kind of awkward prettiness that can charge an image.” “As a bonus,” Berrigan adds, “there is often wit and irony in her paintings….The wit in each case is almost accidental; one need not make bright remarks if one has a witty eye.” In a 1971 interview with Tom Clark, Berrigan would echo his remark about Freilicher to describe the trembling, associational rhythms in his own poems, calling it his “awkward grace.” Like Freilicher, he wanted his work to be “emotionally specific,” and for her paintings, like his poems, “style is in part the product of her concern for ‘style’ as opposed to ‘a style.’” As his title suggests, writing about Freilicher was a way of articulating a relationship between painting and poetry that Berrigan saw himself circling around in his own work.

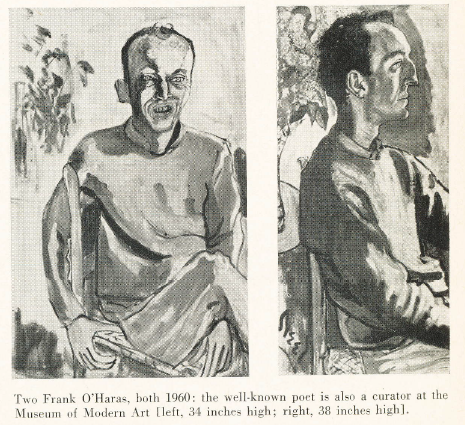

Berrigan also doesn’t miss the chance to celebrate Freilicher’s representations of three of his favorite poets, her portraits of O’Hara, Ashbery, and Schuyler. That he was describing paintings of poets whose own work Berrigan dedicatedly appropriated from allowed him a moment of postmodern framing not lost on the poet. The 1951 portrait of O’Hara, he notes, channeling the painting partly into his own lived version of the early ‘60s, is “a spookily accurate likeness of the poet holding forth in handsomely dingy Lower East Side décor. It’s color range is astonishing; its realness, almost appalling.” Perhaps poking fun at Ashbery’s long sojourn in France as well as his influential poem “Europe,” Berrigan likens his 1954 portrait (now lost) to an unlikely assemblage of real and fictional Continental authors: “Ashbery, in more solid, somber tones, suggests Malte Brigge or perhaps an Irish Franz Kafka.” Boisterously proud of his own Irish heritage, Berrigan is having great fun positioning himself next to Ashbery in this remix of romantic and existential literary heritages. Skimming another aesthetic lineage from pulp fiction to High Modernism, his description of Schuyler’s portrait is equally prismatic and witty: “This is the way the detective of your dreams would look–less like Stephen Daedalus, more like Philip Marlowe.” It’d be difficult to find a more astute or funnier description of how Schuyler’s detailed, dreamy poems, detective-like in their attention to the minutiae of the everyday, waver between the painful excesses of self-awareness and the cool veneer of genre campiness.

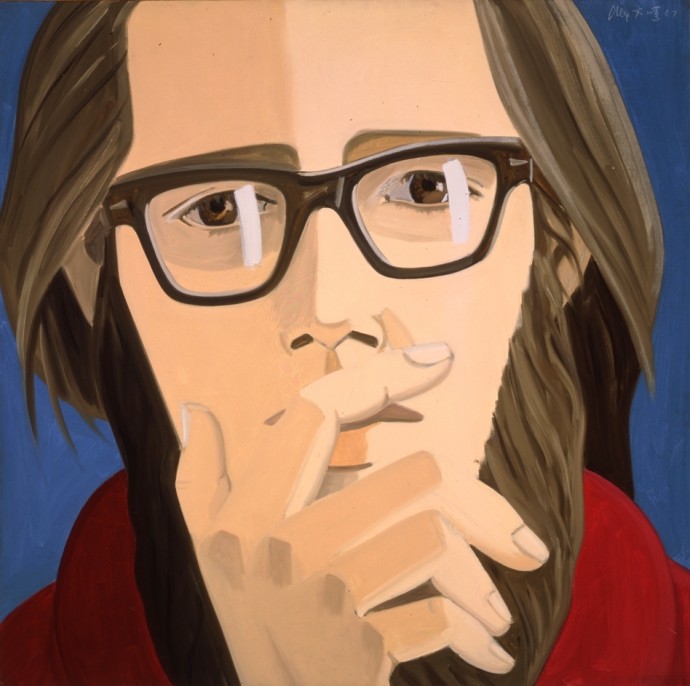

Berrigan’s actual article on Alice Neel, “The Portrait and Its Double,” in ARTnews Volume 64, Number 9, January 1966

Similarly, Berrigan’s January 1966 article on Alice Neel, “The Portrait and its Double,” with its titular allusion to Antonin Artaud, serves partly as an opportunity to arrange and merge various influences. Neel’s two 1960 portraits of O’Hara, which are described in the essay, likely drew Berrigan to her work, whose “fiercely independent realist” style, as he describes it, had been suffering from a comparative lack of recognition under the heroic pressures of abstract painting. Here Berrigan is interested in describing the effects of Neel’s tendency to create two portraits of each individual she paints: the first more stable and recognizable, a casual portraiture; the second more allegorical and symbolic, a way of externalizing interior crisis. He describes her doubling as a process of necessary emotional echoing: “Each second portrait has resulted because Alice Neel has seen another person in her subject. Whether what she has seen makes ‘more’ or ‘less’ of the person, or ‘something else,’ both her vision and the new portrait assert the possibility of other results.” The possibility of other results, of repetition and transformation, is also what motivates Berrigan’s acts of doubling, such as when he appropriates the lines of other writers in order to generate new energies, or when the lines of The Sonnets continually reappear in an out-of-sync parade of echoes. Like Neel, Berrigan’s seriality is prefaced solely on proximity; a subject reappears and they have changed, a book lies open on the table and a sentence lights up with a new presence. This attention to the personal flux of contexts and conditions, to the relationship between surface and depth as meaning, is incredibly important to Berrigan and he sees this vision in Neel’s engagement not with what she represents, but with “how things look” to her.

His explanation of this difference in Neel’s painting gives him the opportunity for a terrific anecdote, as he quotes her saying “‘Look at that hand,’ she will say of someone on the subway, ‘isn’t that wonderful! It looks like a chicken-wing!’” It’s an odd way of backing up his aesthetic description of Neel’s paintings, but Berrigan’s use of the chicken wing transformation acts as his own portrait of Neel, one that displays her ability to spontaneously integrate the everyday into a personal universe that he seems to delight in for its slightly madcap, stubborn freedom of perception. Neel’s work is all-encompassing and cinematic, he suggests, but with the viewing reversed: “posing for her is an experience the way that going to the movies is–when you are the movie.” “As often as not, like movies, your stills turn out to be misleading,” he writes, “When that happens Alice Neel makes you a double feature. If you don’t like yourself, best not to sit for her, unless you love painting.” Again, rather than content, process and material are celebrated as the difficult, tingling necessities of art.

The complex layering of internal and external desire, the momentum shifting the self out of the singular, the anxiety and excitement of being seen, or more accurately, being made, these are also concepts swirling in Berrigan’s own works, especially his well-known long poem, “Tambourine Life,” which he was writing while corresponding with Neel for this article. About how the pleasures of the mundane and occasional run up against the sudden, desperate need for transformation, “Tambourine Life” ends with the unexpected death of his friend Anne Kepler in late 1965. As Berrigan told Clark Coolidge in a 1970 interview, as he was writing “Tambourine Life” “my whole life as it was just stopped, kind of. And I had this poem….I was about ready to finish this poem, but now I’m a different person, I can’t finish it like the way I was.” With Neel’s serene and troubled double portraits in mind, the crisis of a multiple, indeterminate selfhood in Berrigan’s lines “everything is up in the air // especially us, who are me” rings out with a lived equivalent–that between the beginning and end of the poem, the painting, as in life, we are radically changed. Because the world continues, other results reign.