The Opposite of Poetry is Oppression: An Interview with James Gendron

18.03.14

Published in March of last year by Octopus Books, James Gendron’s Sexual Boat (Sex Boats) is a collection of poetry that lives in a black or white world; there’s simply no way of being meh about it. With poems that, in their entirety, read “If I had to enslave someone,/I’d definitely choose a white person.//It just doesn’t seem as bad;” with poems that bear the titles “Licking Your Pussy ’04” and “I Hope You Die Before I Get Old,” it’s nearly impossible to be on the fence about Gendron’s work. You love the book, you hate the book, but, unlike so so many other contemporary poetry collections, you don’t read half of Sexual Boat (Sex Boats) and then forget about it semi-immediately. Gendron is writing the poetry that Poetry might be writing if Poetry A) lived in a van down by the river; and B) realized that, circa 2014, there are a lot of possibilities out there and, as Poetry, Poetry owes itself and its continued existence to search and write those possibilities out. I asked James about René Magritte, Portland, Maine vs. Portland, Oregon, his poetic influences, his compositional practices and, of course, the Notorious B.I.G.

FZ: In your opinion what is the opposite of poetry? And how does that definition figure into your own poetry?

I guess the opposite of poetry would be something like, “the rest of the words in the rest of the orders,” or “teh worst words order in dumbest the.” I write a lot of things that fit that description, that are inept and inarticulate, and that approach the inverse of the beauty of poetry. And, though I’m happy you invited me to do this interview and came up with these great questions, I’m nervous, too. Because the idiocy of my poems is real. That’s really how I think and speak—by choosing a favorite stupid thing to say, then another, then another. It’s like being a musician, but only being able to play the fart machine.

So I’m grateful to live in a time when poetry has absorbed so many things that once seemed like its opposite(s). The things I write shouldn’t be poems, but they are, and that makes me happy.

Actually, it’s hard to think what the real opposite of poetry might be.

Actually, I’d like to change my answer: the opposite of poetry is oppression.

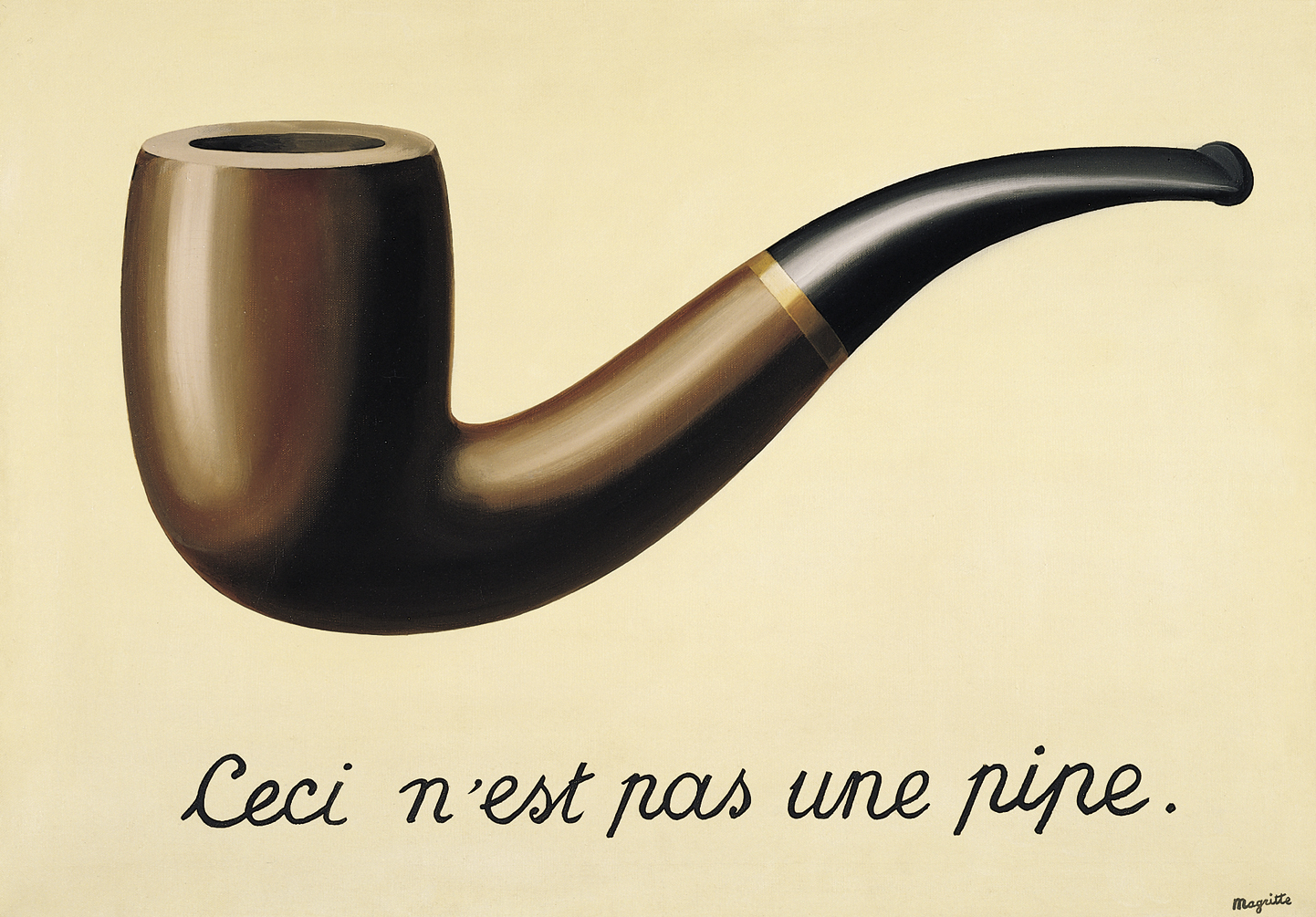

What importance does René Magritte’s painting “The Treachery of Images” play in your life/ on your arm?

In 2005, I was living in Queens and working at The Strand, but I had no tattoos—not even one!—so the situation was clearly untenable. One day, I was flipping through an art book I was supposed to be shelving, when I saw that image. I got the tattoo that weekend—Easter Sunday, 2005.

One annoying thing about this tattoo is that the text is in French, so I often have to translate it for people, and then they ask me if I speak French, and I have to say no. One good thing about having this tattoo is that people often ask me what it depicts, if not a pipe, and I just say exactly, and then give them a knowing look.

There’s something kind of obvious about Magritte’s work. The questions it poses are obvious. “What if a guy had an apple in front of his face?” “What if a face had tits on it?” But I love him anyway. He really seems to want to please the people who look at his paintings. He’s like a surrealist golden retriever.

When discussing your work people invariably mention A) its humor; and B) its tenderness. Those two qualities might seem to converse one and other, yet your poetry would seemingly testify otherwise. My boy Samuel Beckett famously said that, “”Nothing is funnier than unhappiness, I grant you that. Yes, yes, it’s the most comical thing in the world.” Do you agree with Beckett? And do you yourself find your poems funny? Or are they simply proof that you exist and have a particular way of existing, a way different than other people’s ways?

When I was about five, my father told me the funniest joke I have ever heard. We were at Lisa’s Pizza, a now-defunct local chain that did pizza and french fries and was therefore the greatest restaurant I had ever heard of. My dad pulled an enormous fry off our tray and said, “This fry is so big, you could strap it to your shoe and go skiing.” That’s my first memory of laughing to the point of physical pain. Ever since then—and maybe before—I have wanted to be funny.

But I wasn’t funny—not for a long time after that. I made adults laugh so rarely that, when it did happen, I asked them to explain it back to me. Usually, they were only laughing because I had said something inadvertently adult. I drove my parents crazy with that.

In college, I briefly aspired to be a stand-up comic. I read a lot of your boy Samuel Beckett (did you know he used to hang out with a young André the Giant? Is that common knowledge?) and definitely subscribed to his view of comedy. My poems from back then, one or two of which made it into the book, are always trying to be a) funny and b) sad, in that order. But I eventually started to feel limited by that.

I no longer make a conscious effort to be funny when I write. At this point, my poems are basically a record of the best poem-ideas that occur me while writing. It just happens that most of my insights are also jokes. It’s like a pathology.

In three sentences or less, what are the primary differences between Portland, Maine (your hometown) and Portland, Oregon (your currently-living town)?

1. Portland, Oregon is probably one of the best cities in the United States to live as a poet right now: the community of writers is amazing, the rent is reasonable (for now), and there are even a lot of non-poets who like poetry and come to readings and buy books.

2. Portland, Maine is one of the most beautiful places I have ever seen.

3. Portland, Maine has the Amato’s Italian sandwich.

Is this interview making me sound fat?

In Sexual Boat (Sex Boats), there are quite a few serial poems, most notably in the book’s second and fifth sections—“Money Poem” and “French Cinema”— as well as the book’s title poem, “Sex Boat,” a work that shows up semi-irregularly throughout the collection. What was your composition process like with regards to the writing of the aforementioned pieces? Do you ever consciously set out to write a serial poem? Does it just kind of happen? Or?

“Money Poem” was written in two bursts in 2008 and 2010. I had never written anything longer than a page before, and I wanted to challenge myself. I figured my best shot would be to write a bunch of short, related poems and arrange them after the fact. A few months after I wrote the first batch, the financial crisis happened. I’m not saying I predicted it, but I’m not saying I’m not saying that.

“French Cinema” was undertaken in a similar way: I had a conceptual frame for the poem (I was writing from a prompt), so it was easy to make the pieces fit together.

For the “Sex Boat” poems, I cheated: they were all originally untitled. I’m bad at titles: the only one I ever really liked was Sexual Boat (Sex Boats), so I decided to spread it around.

Right now, I’m working on my first long, non-serial poem, and it’s grueling.

“Licking Your Pussy ’04,” “Survey on Luck,” “Does The Hospital Deserve My Love?”—the titles of some of your poems are occasionally non sequitur poems in and of themselves. How important is a poem’s title for you when you’re writing it? Do you often start with the title and then write the poem from there? Title it only after you’ve written it? Or?

As mentioned above, I hate most of my titles, and usually delay titling my poems for as long as possible. The poems named above are rare exceptions, cases where the title suggested the poem, not the other way around.

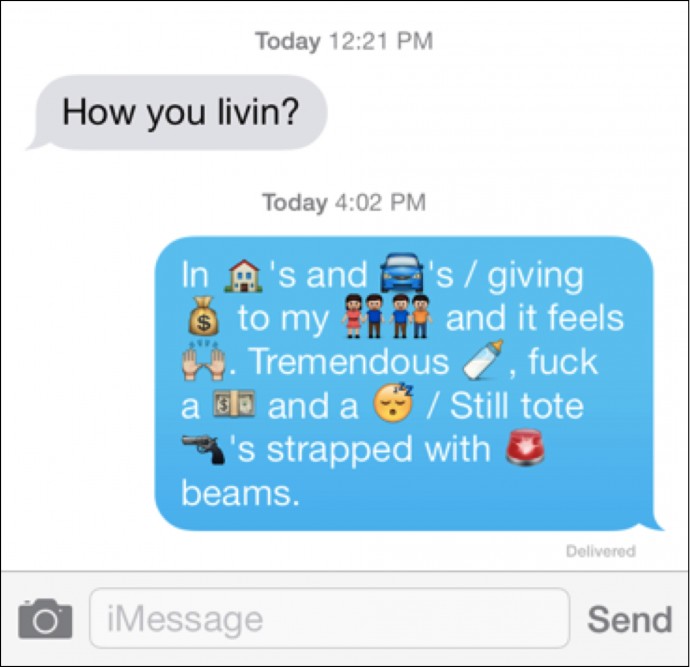

Biggie or Tupac and why? (Also be aware that the correct answer is Biggie.)

I would like to submit the following screen capture in answer to your question.

Sexual Boat (Sex Boats) was published by Octopus Books in March of last year. Has your life changed at all since its publication? Have you been perpetually showered with roses and acclaim and swaddled in Alizé and power? And how long did it take from the writing of the book to its eventual publication? Long process? Short process? Anything you’d do differently?

I sent the manuscript to Octopus about a year before its eventual publication. For the first eight months, nothing happened. Then, we sprang into action.

The best thing that happened because of the book was that I got to go on tour with the great Amy Lawless. Imagine a vacation where, every night, people gather to hear you speak, then give you money. I was also able visit my mother, my brothers, and many friends I hadn’t seen in years. It was like a dream, except I never forgot to wear pants.

One thing I might reconsider is the title. I like it, but it creates a lot of awkward situations. “What’s your book called?” my aunt asked me at my grandmother’s wake. “What’s your book called?” my coworker at the Oregon Symphony wanted to know. “What’s your book called?” asked a tenth-grader at the high school where I recently completed a residency. And, of course, when I made the mistake of passing the book around the classroom, they instantly found the poem “Licking Your Pussy ‘04.”

But no, my life hasn’t changed—and I’m glad, because I like my life. The book and I have basically parted ways at this point. Every now and then, I read something nice about it on the Internet.

Let’s do the influence question—while writing Sexual Boat (Sex Boats), who/what were your primary influences? And by influences I don’t only mean literary—also geographically/musically/relationship-ally/friend-ally/etc. Are you someone who is easily influenced or do your pride yourself on being a lone ranger of creativity? I’m also curious about anti-influence as well. Specifically, are there writers (dead or alive, Bon Jovi represent) or schools of writing that make you not want to write? Furthermore, are you someone who is a “Poet” all the time or do you go days/weeks/months without writing something that you deem “poem?”

The book took a long time to write. It took ten years of actually writing poems, plus nineteen years of…miscellaneous. I came to poetry reluctantly. I learned in high school that a poem is basically an essay wherein each noun has been replaced by a second noun that “symbolizes” the first. It sounded like the exact opposite of everything cool.

There were three artists who changed my mind: Shakespeare, Bob Dylan, and Hannah Williams, my high-school girlfriend. She was a poet, and much cooler than me.

It wasn’t until I read James Tate as a freshman in college that I thought, I can do this. In general, the mysteries of a work of art reveal themselves to me instantly, if the thing is funny. I never would have guessed that there was such a thing as a funny poem until that day.

I just moved into a new apartment last weekend, and I finally shelved my books today, so let’s see here. Some of my faves are: Michael Burkard, Anne Carson, Aime Cesaire, Lydia Davis, Emily Dickinson, Federico Garcia Lorca, Kenneth Koch, Dorothea Lasky, Sylvia Plath, Tomaz Salamun, Gertrude Stein, Tomas Transtromer, Jean Valentine, Cesar Vallejo, and Walt Whitman. I also learned a lot about writing from Ghostface Killah, Stephen Malkmus, Syd Barrett, and Missy Elliott.

Missy Elliott > T.S. Eliot.

Also, happy birthday to Elizabeth Bishop! 103 years young.

Nobody is an anti-influence, really. Everything makes me want to write, but everything else distracts me.

In your The Conversant interview with the aforementioned Amy Lawless (who, I agree, rules), you asked her the following question: I’d like to know which, if any, of the following you believe in: the afterlife, aliens, angels (including Satan), the astral plane, astrology, augury, crystals, fate, ghosts, the rule of law, the soul, soulmates. Lazy-like, I will ask you this same question. And if you do believe in any of the above “things”—several of which (crystals/angels/fate/the rule of law) are referenced in Sexual Boat (Sex Boats)—are they simply “things” to write about and ponder or actual belief systems that you subscribe to?

I don’t think there’s definitely not an afterlife.

It’s a near-certainty that there are, were, or will be aliens, but that’s not really what this question means. The question means, do you believe in weird little space-goblins who speak English, push flying saucers, and smoke weed? And the answer to that question is a robust “I hope so.”

I used to be Catholic, and still try to be inspired by the example of Jesus, an all-around great guy who stood up for the oppressed and believed that people should love each other more. That being said, I’m no longer fully convinced of the supernatural aspects of the faith. I believe in the version of Satan you get in Milton or Blake: a heroic symbol of rebellion against overweening authority.

I believe that crystals are cool-looking.

I don’t believe in ghosts, but I do believe in being haunted.

And finally—you mentioned above that you’re “working on [your] first long, non-serial poem;” you mentioned that it’s “grueling.” Why has it been grueling exactly? And what’s next for James Gendron and the world of literature? Anything specific you’re working on that you want the children to know about? Anything forthcoming?

I’m working on a poem right now that I hope will be long enough to fill a book. It’s called “Weirde Sister,” and it’s told from the point of view of a witch in Early Modern Europe. I’ve been doing a lot of research, which has been fascinating, but the writing has been a grind, mainly because I haven’t actually been “writing” very much. I’ve had a busy few months.

My plan is to finish the poem sometime this spring, publish a few excerpts in journals and so on, and then publish the whole enchilada with Octopus.