Solipsistic Complicity: On The Neon Demon

02.08.16

The Neon Demon establishes a new high point for prurient male art-student bullshit in film. It is one of those movies where the vividness of the imagery is so intimately bound up in the smug puerility of the themes—ostensibly Big Ideas about Beauty! and Violence!—that most of the impact is cancelled out. The director, Nicolas Winding Refn, has always trafficked in the visceral and shocking, sometimes to great effect, as in 2011’s Drive. He appears to be dealing in diminished returns lately: Refn’s previous film, 2013’s Only God Forgives, ended with Ryan Gosling cutting opening the stomach of his dead mother and shunting his fist into her womb. That’s a pretty high bar to clear, in terms of offensiveness, even if you expand the pool to include the work of Refn’s equally intentionally provocative friend Gaspar Noe (Enter the Void). The Neon Demon clears it by being so exhaustingly, pretentiously offensive that, by the time Sia is playing over the credits, you’re left to wonder whether there was any larger meaning to it all.

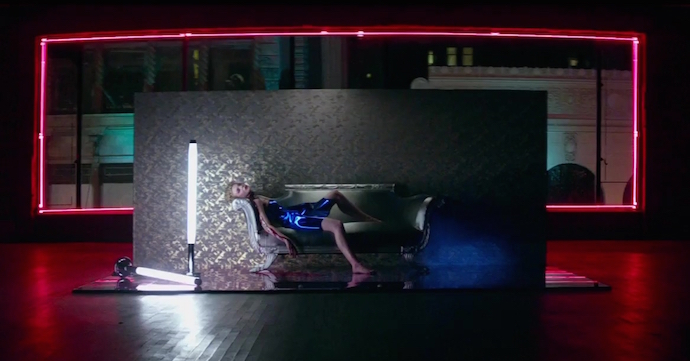

The Neon Demon stars Elle Fanning as Jesse, all of sixteen and newly arrived in Los Angeles to begin a career in modeling. “I’m pretty,” she explains to a friend, “I can make money off pretty.” The first shot finds Jesse sprawled on a duvet with her throat slit; this turns out simply to be a photo shoot, but it establishes, somewhat unsubtly, the film’s concern with the objectification, and mortification, of the female body in modeling. At the shoot, Jesse meets Ruby (Jena Malone), a makeup artist, and they attend a sophisticated party. Ruby and Jesse watch “the show:” as lights strobe and demonic dance music plays (Cliff Martinez’s score, quite good, has things in common with his work on Drive), a bound woman ascends slowly into the air. It’s a gorgeous scene and does a lot to suggest the darkness and grandeur and seduction of this new world Jesse is trying to enter.

Ultimately, Refn’s critique of the superficiality and cruelty of the fashion industry is distinguished from so many others by being more extreme, as opposed to more original. Jesse’s career takes off very quickly, attracting the attention of two veteran models, played by Abbey Lee and Bella Heathcote (Lee’s last prominent role was The Dag in Mad Max: Fury Road, so this was always going to a step down, relatively speaking.) The models despise Jesse but also envy her, viciously, and they and Ruby frequently declaim on how Jesse is so “beautiful” and “perfect.” In contradistinction to these women are the men: both a photographer (Desmond Harrington) and a designer (Alessandro Nivola) take on Jesse as their muse, but their behavior is never depicted as anything less than chauvinist and controlling. Enmeshed, these two aspects of the film seem to offer the potential for interesting commentary on the internalized misogyny of women in an industry dominated by the male gaze, or even on Refn’s own complicity within that system. Refn doesn’t pursue that line of inquiry too far, although early scenes, such as one where Harrington directs Fanning to strip for a shoot, introduce a disturbing undercurrent of incipient sexual violence that pulses under almost every scene (Keanu Reeves contributes to this, playing possibly his most repugnant character ever).

It’s Refn’s own impulse towards the visually ostentatious that both distracts from these ideas and pushes them into senselessness. A cougar appears in Jesse’s motel room at one point; at another a torrent of blood erupts from Ruby as she lies supine under a full moon. During a fashion show, Jesse is transported—somewhere else, where she seems to commune with the Neon Demon of the title. This entity (which looks suspiciously like an upside down Triforce, incidentally) produces a distinct change in Jesse’s attitude towards herself and her beauty. That at least seems to be the idea, but the script can’t commit to the role it wants Fanning to play: the scene ends up looking like so much derived-surrealist indulgence. Fanning, to her credit, is very good at conveying Jesse’s vacillations from naiveté and panic to icy, terrifying ownership of her own power, depending on the scene. The larger problem is that the other characters, and the film, demand that she embody a kind of impossible, inhuman level of beauty, somewhere past youth towards divinity. Fanning either can’t or isn’t given sufficient opportunity to convey that.

The Neon Demon begins to escalate, drastically, in its final act: it contains much of the depravity you were probably anticipating and things you probably had the wherewithal not to expect. It’s in the film’s last third that the threat of sexual violence really becomes manifest, first through Reeves and then through Malone, whose character attempts to rape Jesse. This doesn’t work, and it’s beyond being sickening to watch: Jena Malone usually excels at projecting a kind of tough-minded decency, so seeing her transition from Jesse’s protector to her predator feels strangely forced. From there things somehow get more tasteless: there is necrophilia (arguably the culmination of earlier themes in the film but, still, gross), serious bodily injury and, finally, cannibalism, when Ruby and the models corner Jesse and devour her wholesale. The film ends as Heathcote vomits up Jesse’s pretty blue eyeball, kills herself, before Lee promptly raises said regurgitated eyeball from its puddle of vomit and eats it, perfunctorily. As the credits roll, Lee strides through the California desert in a leather jacket, and a confusingly cheery inter-title proclaims the movie is dedicated to Refn’s wife, actress Liv Corfixen.

Is there an argument to be made that there’s some bizarre undercurrent of feminine empowerment in this story of murder and vampirism? By this point, the average viewer is probably so inured to this kind of shit not to care. The majority of The Neon Demon feels contrived, a string of provocations that suggest the solipsism of its creator, but that aren’t resonantly provocative in themselves. There were more than a few moments of extreme, physical discomfort on my part watching The Neon Demon, but by the end my sentiments had hardened to resignation, annoyance, and a firm doubt that I’ll remember much of the film in a few weeks.