A Pornography of Nods: On Gaspar Noe’s Love

21.07.16

When I heard that Peter Sotos had become friends with Gaspar Noe my excitement for the latter’s Love was overwhelming. I’ve been a diehard fan of Noe’s since watching his Irreversible after someone discouraged me heartily from doing so. In weeks thereafter I watched I Stand Alone, as well as his first—and arguably one of the most jarring things he’s done—longer work Carne, and I was completely obsessed. I seldom glom onto directors with a strong sense of identification, or desire to work in the vein they’ve established, but when I do it’s because they’ve rendered an aesthetic so similar to what I’ve hoped for in art that it feels like returning home. In some ways Noe could be described as a filmic equivalent of Sotos, though certainly less blatantly abject; instead, Noe’s works are stylized accounts of extremity, often done so in a manner extreme. I Stand Alone is perhaps the greatest philosophical retort to the self-congratulatory woodsprance of Walden, offering a guts-level account of solitude, and entire subjectivity driven to the point of murder, incest, and a spree of pacing rants to passersby. Irreversible is, in its way, a feminist touchstone similar to Baisé-moi, wherein the rape-revenge horror trope is expanded and warped into a prolonged look first at the abject, in humanity, and then something entirely opposite, an almost edenic look at a solitary mother figure after the grotesque fucksprawl has been exhausted.

Then came Enter the Void, an intensely performative film depicting Noe’s foray into underground clubs, hallucinogens, and death itself set in a neon-smeared Japan. This was the first of Noe’s work I saw in theaters, in particular at the Music Box in Chicago, a large hall wherein an old man played the organ before the premiere. I went and was able to completely close my head, to the extent that what remains from that work are glimpses of rutting bodies, aborted fetuses, penetrating phalli, and coiled human experiences strung together with brightly-lit trails and throbbing sound; all of which seems traceable to the hallucinatory tail-end of Kubrick’s 2001, a film Noe has praised constantly as the key inspiration behind his practice.

All told, then, when I suddenly saw Love available online after seeing its cumprinted cover and minor scenes here and there, I sat down immediately to watch. What I saw brought pretty much constant consideration, while watching, as to whether I should continue watching. I knew fairly early on that I wasn’t going to experience the promise of his former films, but things persisted in this vein until I found myself making excuses in hopes that I’d warm to its effects later on.

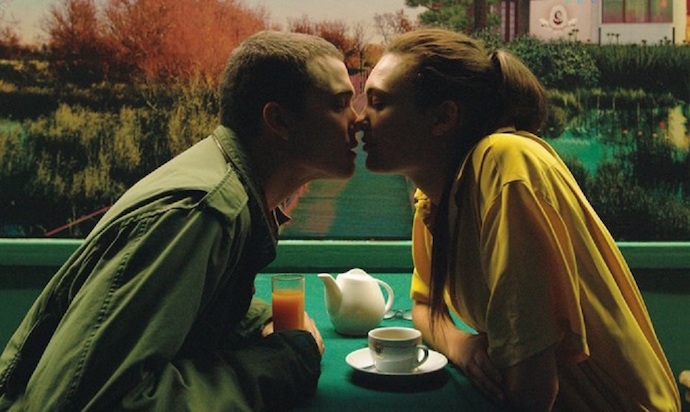

It opens with one of the more thorough masturbation scenes I’ve ever seen, porn or otherwise, wherein its starlet—a girl who’s perhaps committed suicide, who’s longed-for by the protagonist, an oafish film student who’s kind of a younger iteration of Vincent Cassel’s character in Irreversible, but intolerable and pretty uninteresting, and violent only toward the girl who’s had his child and thus “trapped him” in monogamy and the domestic life—ahem, its starlet rubs our protagonist’s cock until small pains start to crop up in the viewer. At first I thought, ah, good, it’s essentially a filmic painting, a slow work that Bela Tarr might’ve made when he first discovered jacking off. However it persisted in a way that wasn’t interesting, it felt exhaustive more in the way someone saying “I dunno” to any suggested activity feels exhaustive. Their bodies are portrayed wholly and thus I guess it might be read as a commentary on how uninteresting we are, physically—“sex is boring, Sidney!”—but it felt more like a botched nod to Last Tango in Paris.

The one undeniable strength of this film would be its choice of soundtrack. I say this not because it’s all boring visually, it isn’t. Much of the film is completely stunning to look at, and the end features one of the more touching images I’ve ever seen of humans bathing; but its music is still the most definitive statement the film seems to make. Featuring a smattering of film tunes from Bobby Beausoleil’s score to Kenneth Anger’s Lucifer Rising, to Goblin’s Dario Argento stuff, there’s also a complete utilization of Maggot Brain, and a number of other pretty clear nods to transgressive cinema, artwork, and music.

I’d heard both Gaspar Noe and Lars Von Trier essentially claim that their most recent works were going to be porno films. This is interesting, compelling even. Von Trier of course made Nymph()maniac, a modern-day 1001 Nights with fratboyish asides courtesy of Shia LaBeouf. Noe made Love. Now while I’d credit Noe with accomplishing the promise of creating a porno as his next feature, while Von Trier fell into some pretty obvious narrative trappings, I can’t help but feel cheated by the end product from Noe. Consider, for instance, if this had just been released via Pornhub, or Redtube, or Xvideos. If Noe had literally gone through the motions of the contemporary porn industry to release the exact same film, this review would likely be entirely different. He did not, and as a result the product is filled with intent and ambition, sprawling with nods and brief winks, none of which amount to much more than quick hopes in the mind of the viewer that a more substantial work will soon be unveiled.

At this point I’d like to articulate something clearly. Often I’ll read reviews by longtime fans of a given artist, who’ve tried to like the most recent thing and just couldn’t. Their tone often seems to come off as a list of suggestions, things that worked in the older stuff that should be brought back, or decisions that were made that would’ve been better if done thus. If this, so far, has read that way, then I do apologize. I’m not interested in giving Gaspar Noe advice. I’m not interested in telling any artist what they ought to do. What I’m interested in here is the out-and-out fandom I felt—and still feel—for Noe’s work, that simply could not make Love compelling no matter how it was conceived.

I’m a fan of failure, in art. I’m far more interested in the works of a given “master” that were shit on, berated, and smeared on their release. With Noe, however, there’s a different dynamic at play. Noe’s work, his previous films, rather, were and are shit on. The dominant narrative of world cinema does not—I’d argue—include Gaspar Noe, and if it does it’s only as an alternative sideshow, but more typically I’ve heard his work reduced to the likes of The Human Centipede, discussed for their shock value, but often qualified with no desire to continue viewing. Salo’s perhaps the most appropriate comparison to his early stuff; a work arguably thick with political antagonism and philosophical inquiry couched in abject content, visual rhetoric that sucks its message deep into the crust and muddle of the hive mind. I’d comfortably use any of the last descriptors to refer to Noe’s first efforts, but with Love I’m just not convinced. There’s little to no abrasion, which I’d hoped for. There’s really an abominable moral strain running through it about fatherhood, family life and the artist—something closer to Jack Kerouac denying his parentage when accused than Alexander Trocchi living beyond squalor and encouraging his wife to sell herself for their heroin (I’d advocate for neither as a literal life activity, but the former seems interested in preserving a false message where the latter bathes in filth, and the same dynamic might be said to exist between Noe’s early work and Love).

Another problem that’s often been on my mind: why write negative reviews? Especially so when one loves any of the creator’s other work. I don’t know that I have a definite answer to this, but I think it has to do with dulling. I’m all for experimentation, completely altering modes between projects and seeing what comes of it. This doesn’t seem to be the case at all with Love, rather, it’s a bad mixture of some of the more lamentable qualities of Noe’s past modes. I don’t enjoy reading negative reviews unless I too hated the work being discussed, so I can’t say this is with the hope of opening a debate about a text that I’m maybe misunderstanding.

I might be misunderstanding Noe in some broader sense–I might be misunderstanding Love–but as I’ve come to view his works, and as they’ve meant so much to me I’d daresay they kept me going at certain points, I’d say there’s full understanding. Can I forgive this kind of thing? Absolutely. Do I still look forward to his future stuff? Probably even more now—one thinks of Akira Kurosawa’s suicide attempt after the awful reception of Dodes’ka-den and his follow-up Dersu Uzala/The Hunter. I’d still much rather see Love than 95% of what comes out in theaters, and I’ve told myself this when I thought I was being too critical; but I think this is a mistake. Disliking something is good, depending. If you dislike a text, a film, a book, whatever, you should own this wholly. Exactly why I won’t say for certain, but I do think it helps establish a personal aesthetic more honest, more attuned to who you really are.

This is actually one of the more underrated aspects of looking at culture. Decide you dislike something political, you’re fucked. Discuss that somewhere, you’re fucked. Decide you dislike careerism, academia, institutions, parenting, whatever, you’re arguably pretty fucked. Decide you dislike a book? A movie? In certain circles you might be fucked, but that’s a problem. If we’re that sensitive about another’s reaction to something is our own fully meted out? I’d argue not.

I’m from the Midwest, so this is as much an admonition to myself as any potential reader. I think discussing what we dislike in art is proper, and healthy, and can lead to people exerting negative tendencies in ways that don’t result in entire hatred of all things. Entire hatred of all things has its place, sure, but the other side of this airing of grievances mentality might be more thorough engagement with art itself, and what art legitimately saves one from the bleach of being.