The Mountains Are Strip-Mined: A Review of Scott McClanahan’s Hill William

04.11.13

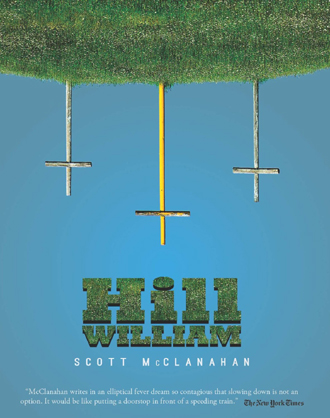

Hill William

Hill William

By Scott McClanahan

Tyrant Books

162 Pages

As children, how aware are we of context in our environment? A first-person narrative, particularly one framed by the present-day, where a narrator recollects past events, brings with it a baggage that can act as a heavy weight for the critical reader. We are expected to not only ignore the dilution of memory with time, but to also believe that the realizations of the narrator as an adult (in this case roughly in his early 30’s) clearly reflect the same of the narrator-character at a young age. When executed poorly, it can act as an oversized, clumsy piece of luggage––zippers splitting from their teeth, overstuffed and heavy. Even worse, it can often lead to the fictional child being given the dreaded label of “precocious.” In the hands of a writer such as Scott McClanahan, however, the inverse is true, the device acting more like a light, comfortably fitting knapsack. When traveling together, it’s easily forgotten.

In many ways; Hill William itself is a book of inversions, following the logic that what occurs in childhood and adolescence will eventually turn us inside out as adults. Heroes are revealed as regular people, paunchy, smoking cigarettes and giving half-written autographs. Men, young and old, exhibiting behavior that would otherwise be categorized as sexually predatory are humanized. Miracles are found in dysfunction. Nostalgia is avoided like a poisoned well. And children are aware of their surroundings and the ambiguities present in everyday life. The mountains are strip-mined, but there’s more room to ride a bike or a 4-wheeler.

“I could tell his mother loved him and he was a good son and she loved him more than anything in the world,” the narrator says as the final word on a man who tried to rape his friend’s brother.

Whereas McClanahan’s previous novel, Crapalachia, as its subtitle states (in a nod to Harry Crews) is a biography of place, Hill William is indeed a biography of childhood through shit-stained glasses, told with a clean and often hypnotic style that sets out to destroy the binaries of prose and poetics. What sets it apart from other novels that dip into the well of poetry is not what’s said in repetition but rather what is not said at all. Motivations are left for the reader to surmise. The experience of school is hardly mentioned. Even a game of “Manhunt” that ends in a sexual encounter is unnamed by the narrator.

What we are given is carefully doled out. Touchstones of pop-culture (Underoo underwear, Hulk Hogan-era professional wrestling and the television show “Unsolved Mysteries,” to name a few) and commonalities of childhood are used with precision, often leading us away from the warm sense of comfort we usually associate with them into a place of uncertainty. The narrator often finds himself born again and again–McClanahan subverting the Biblical. We aren’t baptized by water or fire, but by shit. The earth is a virgin, waiting to be impregnated. Far from immaculate, in this world we are all gods, each of us with myths of our own.

At the heart of McClanahan’s latest is a sense of empathy, that your pain is his, too. Towards the end of the novel, the narrator as adult sits in his car parked beside the New River at Prince in West Virginia for a day of isolation prescribed by his therapist. Before leaving in disgust, he says aloud, “We wring the pain from the darkness and call it wisdom. It is not wisdom. It is pain.” Amidst the pains and fears of youth, there is a humor and warmth. A football injury leads to a chain reaction of vomiting. A mother, out of her own fears, asks her son if Diet Coke is alcohol for reassurance.

While episodic in structure, McClanahan doesn’t beg to be read in one sitting, he commands it. Bread doesn’t become flesh, rather flesh becomes a book. And with a sincerity that can reach anyone, we’re assured that all of us, like every character that’s brought to the page, is loved by someone. Because as Dorothy Day once said, “If we love enough, we are going to light a fire in the heart of others. And it is love that will burn out the sins and hatreds that sadden us. It is love that will make us want to do great things for each other.” Hill William is just that – an object that turns hatred to love.