A Review of Lauren Shufran’s Inter Arma

03.11.13

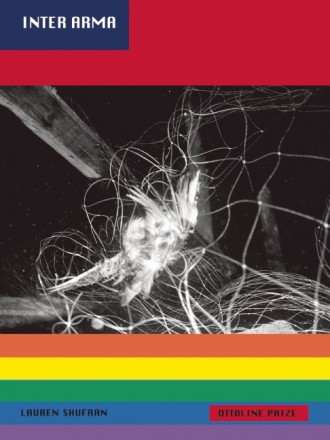

Inter Arma

Inter Arma

Lauren Shufran

Fence Books

92 p. / $15.95

In ancient Rome, chickens were holy. They were bred and held in sanctuaries, near temples, and treated like small clucking godly portents. More than that, they were combat oracles. In fact, any good general worth his feed would check with the holy chickens before going into battle. Toss some seed at their feet and watch: if they eat, all signs point to good fighting, but if they don’t all signs point to slaughter. The holy 8-ball of the ancient world, the pecking little beasts. One famous account has a Roman general named Publius Pulcher consult the ancient chickens on the morning before a naval battle. When the birdies don’t feast, he tosses them overboard, saying: “Let them drink, if they don’t want to eat.” The battle turned out poorly: Carthrage’s fleet trapped Pulcher’s against a cliff face and destroyed the Roman navy. Thousands of men drowned far from home. The birdies were correct.

This is our desire for form. From the scattered pattern of thrown food and the random-seeming movements of the twitchy chickens, we somehow divine a godly sign. It’s an after-the-fact placement of meaning on an otherwise meaningless movement. We want those chickens and their clucks to signify something greater beyond our daily bread, and so we toss feed and listen when they decide they’re too good for smashed-up crackers. When they don’t eat, we avoid the battle. But when they do, and we still lose, other causes can be found (a rude lieutenant cursed Apollo or maybe showed his privates to some virtuous daughter of Rome). It’s a human trait, this need for meaning, but meaning is just another way of saying form. There’s something about it that both stifles and brings about the best in us. Sometimes, the chickens need to be drowned. Sometimes, the chickens need to be consulted against all reason. In Lauren Shufran’s Inter Arma (Fence, 2013), form, meaning, birds, augurs, ancient Rome, and more, all swirl and clash together to make these wholly modern and strangely time-flat works.

Inter Arma is a birdy work. The speaker is a duck, and maybe a duck in the military. It’s a tricky sort of lyricism, made trickier by its punning and playful sonics. That’s its first form: puns, alliteration, and sound. These puns and sounds form elliptic shapes in the poems, reflecting and refracting “canard” and “canary,” for instance. It makes these strange whorls where a new phrase is introduced, maybe a play on “duck duck goose,” and suddenly the following poems are all pulled into that stream. It’s almost a flushing as these poems get pulled into their own center. It’s a strange, nagging feeling, where the reader constantly wonders if they’ve read this poem once before. And they have, though maybe in a different shape, but still the same. For example:

“My earthenware’s disturbing to your

Camel and your misters ’cause it seems be-

Nign ’til rashly–like Taxaxippus–it haunts your bud-

Ding hunger. My thyrsus drips with honey ’til

Your hippodrome gets sticky.”

morphs in the next poem to,

“Trust a fig when it deictifies some oth–

Er fig, which fig is keeping time with fags and sec-

Rets. My thyrsis drips like honey does that

Glaucus’ horses wish they took their master with when

Seizing flesh like they were taking pictures.” (pp. 56-57)

These lines hinge around the “thyrsis,” who is a character in Virgil and is linked with the pastoral poem. However, in the first poem, it is spelled “thyrsus,” which is a kind of fennel rod, and makes a lot of sense given the overwhelming cock and sexual imagery. It’s this sort of subtle mutation from poem to poem, a slight twist in vowel or consonant, which gives these poems their slowly squirming feel. Along with that, the poems deal with sexuality in violent and multifaceted ways. For example, pious in public but depraved in private, Shufran links the Roman’s daily double-consciousness with the typical homophobic American male to emphasize both its absurd nature and its hateful ubiquity. In public, the military hates anything outside their tiny in-bred world; however, in private, all those ducks line up together to call each other a “fag.” They love their cocks and “seizing flesh like they were taking pictures.” Meanwhile, the duckish narrator flits in and through these scenes, dropping classic references and speaking in meter. He seems a part of and beyond it all.

Its second form is obvious but tricky. The poems are written in both metered verse and prose blocks. However, the metered verse doesn’t pretend to be wholesome or good; instead, the lines break in the middle of words and the poems sit at the bottom of pages, like a duck in a pond. But like a dead duck drowned from all its own waterboarding, weighted and tossed aside, these poems don’t float, and don’t try to. It’s as if the meter is there to force the poems into lockstep, a kind of arbitrarily rigid shape, but the poems themselves refuse because of what they contain. They stride along in ducky-lines, but press at the edges of their containers. Like the violent metaphors of rape and penetration the army consistently uses, these poems are violent manifestations of ancient formal devices. They jut and move and resist, while still maintaining their strict shape.

In an interview at Trafficker Press with Taylor Brady, Shufran says, “And the more I started writing this text through birds the more this other meter – poulter’s measure – seemed called for. Poulter’s measure is alternating Alexandrines and Fourteeners – or, in the ongoing poem here, iambic hexameters and heptameters.” Shufran’s verse, in other words, is engaged with a strict literary history while also creating these holes, jagged edges, and rutting birdies. Poulter’s measure directly references poultry sellers and how they sold in 12 or 14 bunches, or a baker’s dozen. Both her form and her fowls are connected through this odd, indirect historical misshapenness. It’s a literal chicken connection, but also a connection with a violent history. Bakers used to add an extra piece of bread to their dozen for fear of retribution from customers for potential miscounting or mistakes. This violent etymology of the phrase “baker’s dozen” underscores the violence flitting through these poems.

Aside from being in strict meter, they also have a kind of military chant to their cadence. This is found in the first form mentioned. The twisting repetitive nature of these poems is much like the call-and-response of military marching songs. Inter Arma, moreover, is very much engaged with military presence. The military’s tendency toward hazing in very sexualized homosexual/phobic terms is linked with the treatment and torture of terrorists in places like Abu Ghraib. Lynndie England forcing men into demeaning positions is like the drill sergeant calling his recruits “faggot” in order to haze them into obedience. In both instances, it’s an attempt to dehumanize through rhetoric of shame, penetration, and homophobia. This may be why the speaker is a duck. The speaker has lost its humanity through this hazing, whether hazing of itself or hazing of others. The duck seems to go either way, it’s mutable and fluid. There’s a lineage there, one wherein those hazed and shamed become the hazers and the shamers, passing down this inhuman and gross method of indoctrination. The chicken is a cock, and the cock is central to these metaphors of domination; it’s worshiped as an augur and used as a threat of violence.

Inter Arma is a complex combination of classic form, contemporary schism, homophobic militarism, and ancient texts. Its range is wide and deep in the sense that, while it circles around the same images and themes, it invents different linguistic ways to come at these things. Though it calls and responds, it doesn’t get overly insular. The classical references act as a guiding spine for the contemporary political critique in a really difficult and interesting way. Inter Arma is a chickenish book, but only in the best possible way.

___________

Inter Arma, by Lauren Shufran, is available from Fence Books.