The Literary Dung Ball: In Conversation with Jac Jemc and Amber Sparks

21.08.17

I first met Jac Jemc at at reading in Chicago. It was really neat, after reading her work and being kind of intimidated by her talent, to meet Jac in person and discover that in addition to being a lovely person, she also has a mind a little like mine — insatiably curious, wandering, and deeply concerned with the toughest parts of being a human in a world filled with other humans.

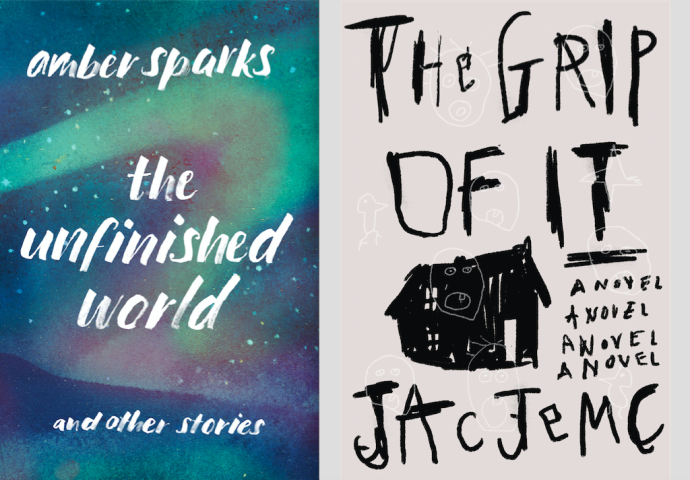

Jac has also continued to be a fierce talent of a writer, sketching characters and relationships that manage to look hard at the gaps in communications with one another and the faults we find in ourselves. Fast forward to her brand new book, The Grip of It, which is a killer haunted house story, and the opportunity to chat with her about it for Fanzine.

Here we are, and here, also, a warning and an invitation: we are both a little enthusiastic and a little verbose. And Jac’s book is terrific. Oh, and a promise: no spoilers below.

AMBER SPARKS: Let’s start with the most obvious question: Why a haunted house story? Did you set out to subvert the tropes, or pay homage? Or did you just have a damned interesting story you wanted to tell that happened to take place in a haunted house?

JAC JEMC: The easy answer to your question is that I’ve always loved scary stories, particularly the idea of a space being haunted. At some point in 2011, it dawned on me that I could try to write one myself. I knew I wanted to tell a story in a haunted house, and I knew I wanted to think more actively about plot and pacing and suspense than I had before. I end up returning to the theme of the gaps in connection between people (family members/lovers/friends) in my work, and a haunted house is a perfect way of externalizing those conflicts, turns out.

As I worked on revisions, I thought about all of the things you mention. Some traditions have been subverted and I’ve paid tribute to others.

My way of beginning a project is really haphazard. At some point this will probably fail me, but I rely primarily on intuition and a sort of dogged commitment to writing a certain number of words every day, even when I feel really stumped. Reading what I just said, I keep trying to interpret what that means about me as a writer: am I romantic or practical? But I don’t think one works for me without the other. I’m so impressed by and jealous of writers who go in with a plan.

What about you? How do you decide what to work on? I seem to remember an exchange, on social media probably, where I said something about how sometimes a story begins when I find myself interested in a random topic and I allow myself to go down the rabbit hole of researching that thing, trusting the associations I pull in, as strategic or random as they might be. Have I totally made that up?

AS: One of the reasons I love your answer here is that I’m actually working on a novel about ghosts who very specifically are not haunting a space, which is kind of weird and challenging and disorienting. It’s been interesting realizing how much haunting is tied to place — sometimes to people, but much more often it’s the space that’s haunted. I’ve been reading your book at the same time I’ve been re-reading Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, which has been accidental and fortuitous. So much of a house, in particular, is really made to be dream-like, or nightmare-like — made to be haunted. I love the idea of the gaps in connections as a sort of echo of haunting, or what fills the space in between misunderstandings. I loved that about your book — it’s as much psychological, internal, as it is any kind of traditional haunt story.

Down the rabbit hole is right — pulling in threads and adding and subtracting and eventually I get something that could be called a book. It takes me forever to write a story or book because of this way of working. I am also so jealous of writers who are like “I want to write about x,” and then they do. I think I eventually get to a book when I realize there’s some kind of internal coherence, however dream-like and odd, to the giant literary dung ball I’ve been pushing around for a while.

How did you train yourself to be more muscular when it comes to the mechanics of story? Any reading or craft stuff or was it just sheer writing and rewriting and rewriting?

JJ: Oh, I love that idea. We tend to default to thinking that ghosts are trapped somewhere, right? Also, in my mind, a ghost always haunts, but is it possible for that not to be the case? Does a ghost exist if it doesn’t haunt? But you’re saying that your ghosts aren’t tied to one particular place–is that right?

I also really connect with that idea of a book being a “literary dung ball” — that keeps making me laugh out loud; the term matches the level of reverence I feel for my work on most days. For me, all of the work has to happen on the page. Sure, I think about it as I reread and revise, but anything that doesn’t get written down, gets forgotten. I have trouble remembering what I want to say in a conversation, let alone in formulating a plan for a book.

But, before I say more about that: you have such a talent for plot! Are you nuts? “We Were Holy Once” or the novella “The Unfinished World”? I think both of those have such strong technical structure! I will give all credit for any mechanical improvement in this book to my agent, Claudia Ballard. She is brilliant and (gently) demanded changes that would help pull the reader through the story, and was patient enough to read multiple drafts as I tried the wrong things and cried on the phone with her, convinced I couldn’t do what she was asking. I hope I’ve retained some of what I learned I learned in that process, but I’m worried that the problems for the next book will necessitate a totally different set of skills. But I think I end up working on the things I do because I like laying out a puzzle and trying to solve it as best I can?

Selfishly, I want to get back to the idea of ghosts though. Do you believe in ghosts? Have you ever seen a ghost?

AS: Ghosts! I’m obsessed with them. But I don’t believe in them, no — at least, not in any sort of supernatural manifestation sense. But I hope they exist anyway? Like, maybe, as residue or leftovers of a dream or stranded time travelers or something? Wouldn’t it be great to have that extra layer in the world? The not-world behind us, or I guess over top of us?

I have seen ghosts, though. Well. “Seen.” “Ghosts.” I’m a lucid dreamer, and I have sleep paralysis, so I’ve had plenty of nights where I’ve woken up and seen someone standing at the foot of the bed, or once I saw a ghost cat. Ghost bugs, too. But I always know I’m dreaming. It’s one of the reasons I don’t believe in ghosts, actually — because I have firsthand experience of where the idea of ghosts and alien abductions probably come from.

Gosh, I want to though: Believe.

What about you? Do you believe in ghosts?

JJ: Your answer to my question is so complicated and perfect. You don’t believe in them. You hope they exist. You’ve seen them. But none of those things determines the other. That sort of complex relationship of understanding is pretty much exactly where I’m at, with the one difference being that I haven’t seen or heard any ghosts myself, but I very much trust people who say they have. I just read this article in The Atlantic about how psychics cope with hearing voices, and how those mechanisms might be helpful to people who are suffering because of the voices they hear. The article articulated some interesting ideas behind what happens when our minds deviate from “consensual reality” and how Western culture is so strictly critical of those deviations. I feel like the idea of ghosts linger outside of that idea of consensual reality, too. I’d need to see a ghost to say a statement as strong as, “I believe in ghosts,” but I if someone told me they’d seen a ghost, I’d believe them.

I do not want to be a ghost, though. I definitely want to die for good. Ready to be dead whenever my time comes. ::Desperate, nervous laughter.::

I want to hear more about this novel of yours though. How is the process different from writing stories for you?

AS: The process of writing a novel is, frankly, alternatively hideously boring and tremendously exciting. Is it like that for most writers? I don’t know about you but I find short stories so much easier in terms of my limited attention span and interest in far too many things. Especially because I write a lot of short short pieces — I’m not saying they’re not difficult or time-consuming, but the commitment is brief and the risk minimal. Short short fiction, in terms of writing, can be a one-night stand. I’m interested in an 19th century scientist and his wife for a minute? Great, one night stand, easy. But am I interested enough for a novel? That’s the big question. When I talked about writing a lot in my head before it goes on the page, that’s a big part of it. I have to have spent enough time with the characters in my head, to be interested in them and their world enough that I can risk a novel over them. I suppose that’s not a very practical way of writing a novel. I imagine most novelists just sit down at the desk and get on with it. Which is, clearly, why I am not a novelist.

Is it like that for you? I feel like you do character so very well. And that’s especially impressive since a constant theme of yours — in the new book, especially — seems to be the missed connections, the ways people don’t understand each other, don’t communicate. How do you manage that so well — allowing the reader to know the characters so intimately while they never really know each other at all?

JJ: Isn’t plot just things happening?! What is plot? I’m having a crisis now. JKJK.

I agree absolutely about the process of writing a novel. I am currently in the hideously boring stage myself. I’m finishing up a first draft, and I know what needs to be done but I don’t want to do it, so I’m making myself all sorts of bargains to avoid the work if at all possible, but that just means I leave it until as late as I can in the day, and then the writing is awful. But maybe I shouldn’t be doing whatever it is I’m doing if it’s such a struggle? Maybe that means I should do something different and exciting with it? I guess I like the long haul of it, sitting with a project for long enough, and with enough obsession, that everything in the world around me starts seeming related to the book, sometimes even more than to my own life? That’s an overstatement. I’m not that out of touch.

Your process of spending time turning the characters over in your head and making sure you’re interested enough in them seems like an entirely practical way to go about writing a novel. Better than starting 100 a books, only to get so far and realize you’re bored.

I don’t usually know my characters before I write a book. I do the old “put-them-in-situations-and-see-how-they-react” test of their mettle. I might even venture to say I know them even less at the end of the book because of what you mention about how I’m sort of always living in that gap of what we think we know about another person but don’t. But that’s probably what makes a character seem more real and human, right? To have them do surprising, unexpected things that surprise both the other characters and the reader.

I know I also have zero talent for setting/description because, in the final stage of edits on this novel, my editor very kindly told me that she had no idea what the town looked like or any of the characters, so could I please add some indicators of those things. Ha. If pressed, I’d venture to say I’m good at metaphor/the turn of a phrase, but even then I think those things can end up making the story rather clunky.

What do you think you’re best at (in writing, though I’ll take answers related to general life, too)?

AS: I love that you say that about “living in the gap of what we think we know about the other person” because that’s exactly what I mean about how people communicate — or don’t — in your books. Ships are always just missing each other! Which is wonderful, and sad, and true, and those gaps are what I think we can write into the very best and oddest ways. You’re so right. Those are where the mysteries and made up stuff live.

Language is the one thing I don’t have to work as hard at. In fact, I’ve had to work much harder to control it than produce it. My writing can get a bit baroque if I’m not careful. Flying buttresses everywhere.

You know, I actually start to wonder if this is true of many writers. Like, the things I think they’re best at — would they always perceive those as weaknesses, and perhaps that’s why they’re better at those things? Just sheer practice, having really worked at it? I have to really work at plot, whatever the hell it is. If it were up to me I’d just have two characters sitting in a setting that I endlessly describe and having witty conversations. This may be also true because I come from the land of theater. So my idea of a good time is a lot of terribly Noel Coward-esque conversation, some drinks and furniture thrown, a scene lovingly set and well-used. You know, the theater critic John Lahr described Private Lives as “a plotless play for purposeless people.” I suppose I really just wish I’d written Private Lives.

What do you wish you’d written most?

JJ: Yes, I do think that maybe the things we perceive as weaknesses are the things that actually might be strongest in our work, but not because of practice. Instead, I think, sometimes, it’s the things we get wrong about what the formulas of those elements (plot, character, whatever) that make them exciting for a reader.

I want to mention that I come from a theater background, too. I majored in both theater and creative writing in college (God bless my parents for not forcing me to pick at least one practical discipline), and I do have an eye on the sound of the words and character objectives at all times.

But oh my god, I love Private Lives. When I was a freshman in college I saw it on Broadway with–swoon-Alan Rickman and Lindsay Duncan and I was like THIS IS ALL I WANT TO WATCH EVER. So dry and smart and perfect. My god, I wish I could write like that. I would give up all my ghosts for that.

But I can’t pick Private Lives because that would seem like I was taking the easy way out. I will go rogue and pick something that is really unlike what I do, but that I wish I was capable of: Jenny Holzer’s book, Living. She is the master of the aphorism, and I think my desire for aphorisms, for words by which I might guide my life, shows up in my fiction from time to time, but I’m so far from doing it well and right. Maybe it’s because of a very strict Catholic upbringing where I was given all the rules, and I like rules. I like being told, “If you do X, you pass,” as much for the purpose of following them as knowing, concretely, when I’ve broken the rules and to what degree.

Do you feel like you break rules? I feel wimpy about the chances I’m willing to take.

AS: Rules! I hate them and break them gleefully. I always have. Maybe because I wasn’t a Catholic? Ha. The first time I knew I was an atheist, or agnostic at least, was when I was in confirmation class (very unstrict Methodists, we mostly played basketball) and for my final conference, the pastor asked me where women came from and I refused to say from the rib of a man because fuck that. He was like, but that’s how it happened, and I was like, well, I don’t actually believe in any of this junk anyway. I think I still got confirmed, which shows you just how lax they really were.

I’d like to say I break rules because I’m so cool and such a rebel but really it’s more because I’m so socially awkward and untutored I don’t really understand that they’re there until I stumble over them. I don’t have a formal writing background or training, so there was never any training to rebel against. I think that’s both good and bad — on the one hand I’m willing to try anything. On the other hand, I don’t often have the formal training I need to deviate effectively from the norm. It’s like painting — how even abstract painters start with life drawing. I didn’t know Raymond Carver until a couple of years ago, so I couldn’t know I was spending years doing a bad Raymond Carver impression.

So, I guess I’d ask one more question: What the one thing you want people to know about your book?

JJ: And I don’t think I need anyone to know anything about the book. Just read it if you’re interested. It will tell you all you need to know about it.

Now I have one more question for you: If you could be good at anything else, but just in, like, a hobbyist way, what would it be? I’ll answer my own question and say that I really wish I had a talent and inclination for gardening. I love the idea of growing my own food, but it seems like such an endeavor and I’m really pretty awful at keeping green things alive.

AS: Mine is boringly obvious to anyone who’s read my stuff, I’m sure, but I wish I could paint. I really wanted to be a painter, and I’m very much interested in art, particularly the women Surrealists like Leonora Carrington. I wanted to be like Sylvia Plath and sketch and paint and write. But I’m so dreadfully bad at painting. I might take it up again in old age, when everyone is very indulgent of whatever silly thing you decide to do, and no one tells you that you’re terrible. I’d like to be foolish and old and making bad paintings someday.