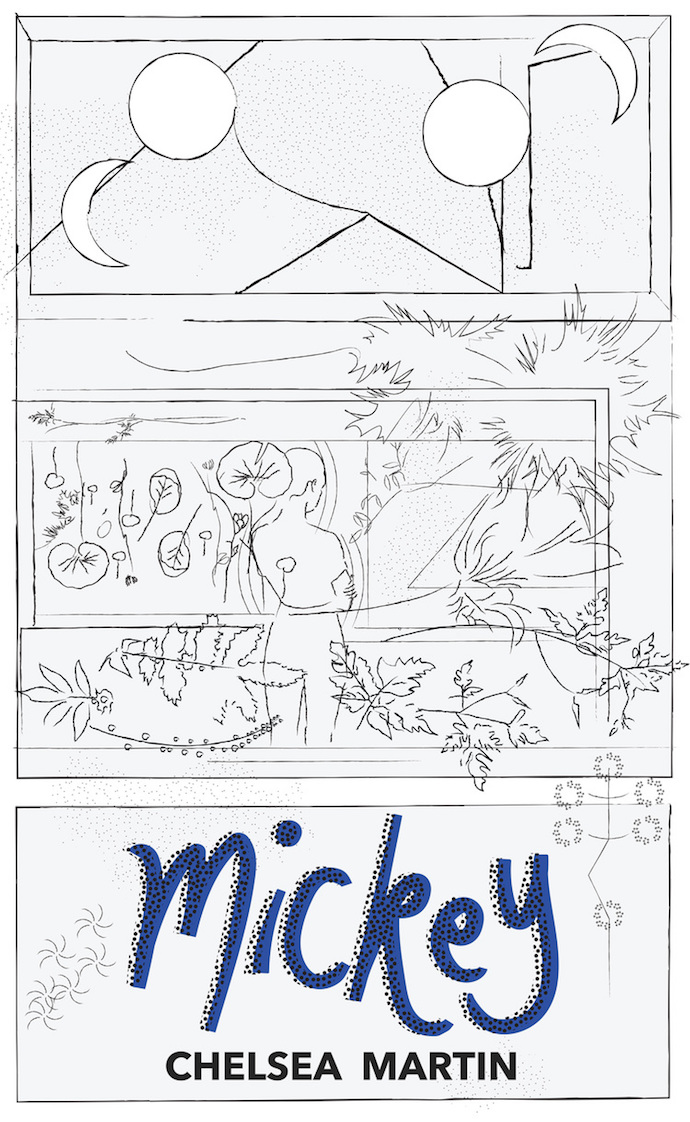

THE INSIDE OF AN OUTSIDER: Chelsea Martin’s Mickey

12.09.16

Chelsea Martin’s novella Mickey is a strange little gem. The story of a break up elongated by the protagonist’s struggles with her mother’s rejection is told through a series of awkward encounters, power plays, art show concepts, and general sense of self-loathing. In navigating the downs of young adulthood as an out-of-work, deeply-in-debt artist, Mickey offers a meditation on the most unsettling of human conditions: in life, you are truly alone.

Martin’s a prolific figure in the internet age. The 30-year-old writer/illustrator has published four books, been featured in anthologies and earned praise from many, including Lena Dunham, though that may have meant more before the Met Gala. She had a comic for the The Rumpus called Heavy-Handed, which was quite good, dealing in the awful intricacies of social interactions using grayscale.

Originally from the small mountain town of Lake County, California, Martin moved constantly growing up. As someone who moved a lot as a child also, I can attest that it manifests later in life as a tendency to observe people as others, rather than peers.

“I feel like people who stayed in one place, their interests were really informed by who their friends were and what was cool at their school, but since I moved so much I sort of had to figure out what I liked on my own,” Martin said via G-chat a few days ago. “I think I became comfortable with feeling like an outsider, even though I hated it.”

Over the course of this summer, which she referred to as “stupid,” Martin’s moved twice, once cross-country.

Effervescent in its anxiety, Mickey takes place inside consciousness, where themes and existential truths are deduced from minutia most wouldn’t even notice. While she and the character share a number of similarities, moving being one, artistic malaise another, the book is a construction of elements from her life manipulated into something entirely different.

In her Catapult essay on writing the book, I’ll Still Be Afraid to Talk to You, Too, Martin explains,”I created a protagonist obsessed with her on-again off-again boyfriend, obsessed with the nature of ‘on-again-off-again,’ which in its nature is always either coming or going, always needing to be defined and therefore something that perpetuates its own existence. It was an outlet to think about what it means to have a role in someone else’s life, how permanent or impermanent it is, what influence one has over what that role is, or how it is perceived, or how important it is.”

Written in a modern style, Mickey favors blocks of white space over blocks of text. Tight prose punctuates the power struggles she’s constantly creating for something to grapple with. Sarcasm is employed as a blatant mask, highlighting the absurdity that ensues when subconscious motives actualize in real life.

In addition to working for technologically shortened attention spans, the book’s pace is satisfying. “I think it feels good to read books that have a lot of white space,” she says. “But it also frees my writing up a lot for some reason. It’s like the paragraphs don’t have to answer to each other or something. A thought doesn’t have to connect to the next thought. Or it can completely contradict it. It feels more natural to me.”

While the relationship with Mickey bobs along the surface, a lack of one with her mother boils beneath. We experience her mother in past and present, neither version reconciling with the other. As the book progresses, delving into her childhood, her mother seems blasé at worst, certainly not someone who would ghost her own child. Flash forward, their relationship has deteriorated to the point where we only view her through the agonizing lens of unrequited Facebook messages and Matchbox 20 lyrics. The refusal to interact never explained, their encounters culminate in a brief conversation about cheese, ending with a pathetic lie.

To me, the book shines mostly because it’s so relatable. Her self-induced cage of depression and laziness perfectly captures the stagnant decadence of unemployment. And it’s difficult to negotiate a break up when you don’t like anyone. Nestling into the vehicle of a failed relationship is easier than going to a bar and meeting a guy that seems okay, only find a Dali elephant tattoo and Bon Iver on his playlist. Martin translates the chill, frothy sadness of staying at home all day while your friends and resources dwindle to nothing, with no prospects on the horizon because you haven’t left your house in days.

Here are some highlights:

On power: “I wanted him to beg to be hurt by me, so that when I hurt him it would be completely his fault, and I would be the blameless agent of his pain who would wipe his tears away from his face and say, ‘Well, why did you make the wounds so deep if you didn’t think you could handle it?’”

On unemployment: “But now I’m home almost all the time and, having exhausted many of my friends’ capacities for compassion, I am able to devote full days to plotting petty revenge and going over my past failures ad nauseam.”

On relationships: “I wish I could push Mickey as far from me as possible while still holding an invisible leash.”

On fighting in said relationships: “I said Yes, and with that we left the world of concrete reality to talk about tones of voices, intent, implied intent, and mood, all of which could never be verified, and could therefore be conveniently misrepresented to serve a point.”

On life: “I’m trying this thing where I’m just letting life pass by as if it’s nothing.”

The themes plaguing the protagonist–debt, unemployment, even hunger–are the norm for many of us recent graduates. On her website, jerkethics.com, the bio reads, “Chelsea Martin paid $100,000 for a BFA.”

When asked about this she says, “So, you know, working as a barista with high school kids after I finished CCA was very depressing. And I did that for a long time. And I sort of worked my way up to office jobs and now I’m sort of doing an art job, but it’s mostly due to all this time I put in doing office jobs after college. Debt is really scary to live with and i guess part of me blames CCA for profiting off of me.”

While California College of the Arts, the Oakland art school she attended, may have cost too much, the Bay Area opened Martin to the world of zines and self-publishing. Zine culture has exploded in recent years, moving from the exclusivity of the punk and hardcore scene to the MOMA and the Gagosian, suddenly viewed as trendy and accepted as high art.

“I love self publishing,” says Martin. “I love it! I think having total control over how something looks, and being able to make as many copies as you want, and selling them and keeping any profit to yourself, all of that feels cool.”

Mickey nails contemporary woes in a way that is honest and sad but more than anything hilarious. Martin creates outsider art for other outsiders, not the kind of outsider art that’s only appreciated once the insane person is discovered dead in a barn with a thousand fantastic paintings. Perhaps it’s the internet, perhaps the recent inclusion of zine culture into pop culture, but the appreciation of Martin’s work is encouraging, however hopeless the subject matter may be. Though she’s been moving too much to write recently, there’s more to come.

“My agent and I have been shopping around my next book to big publishers. i feel hesitant about it in some ways, because I would hate to lose creative control of my work. But I do want to gain a wider audience, and I would like to be given money. But there hasn’t been much interest from them anyway. I don’t have an urgent need to be published by a big press. If it never happened for me, I would be fine with that. I like small presses. And I think with the zine appreciation thing that’s been happening, there is a lot more attention on small presses. I think it’s beginning not to matter what size press you’re on.”